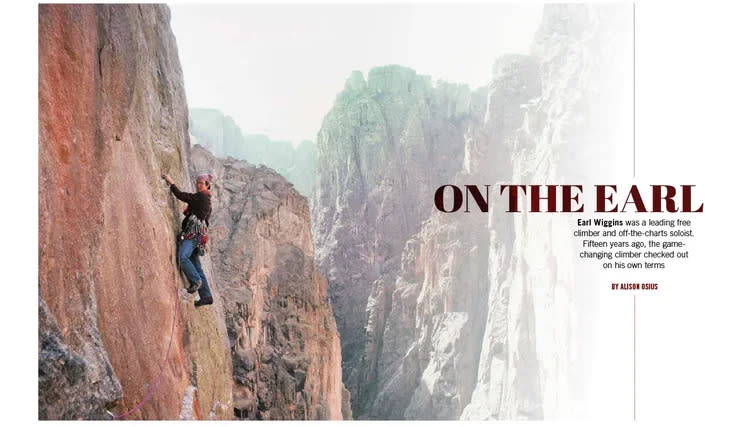

The Daring Life and Untimely Death of a Climbing Pioneer

This article originally appeared on Climbing

This feature first appeared in Rock and Ice issue 247 (January 2018) and is being released for free to honor Mental Health Awareness Month. Please note: This story involves mention of suicide and self harm. If you or a loved one is experiencing suicidal ideation, reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255). Help is present 24 hours a day.

--The Editors

In May 1976, Jimmie Dunn and Earl Wiggins descended into the deep gorge of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Colorado. In an era when multiday nail-ups on the 1,800-foot walls were convention, the Colorado Springs pair cast off with a daypack to try the canyon's first major free ascent.

Their objective, the unrepeated Kor Dalke (V 5.9 A4), had been established over four days in 1964 by Layton Kor and Larry Dalke. Wiggins, on his only other visit to the Black, had come up with the idea to free climb the line after looking at it during a three-day ascent of a connecting route.

"I know we can do it," he had told Dunn.

Their climb of what was later known as the Cruise was a breakthrough, proving that the Black's towering Grade V and VI walls could go free--if you were bold enough.

Dunn, a leading climber of the day, then 27, calls his friend, who was 18, visionary: "I wouldn't have thought of that," Dunn says. "No one had free climbed those walls." Almost no one climbed them at all.

When they blazed the route in six hours, their fellow pioneer Ed Webster exclaimed, "You guys cruised it!" and the name stuck. An American Alpine Journal article by another peer, Jeff Achey, calls the Cruise "one of the most audacious free-climbing days of all time."

Yet even then, Wiggins was thinking ahead--he knew he could free solo it.

"He didn't say it," Dunn says, "but afterwards I could tell he'd been looking at sections and thinking about it." Eight pitches up, on an insecure traverse, "He just happened to climb slow, and Earl didn't climb slow."

Three years later, on a clear October day, Wiggins, 22, stood at the base of North Chasm View Wall with his blue Robbins boots, a chalkbag and no rope.

Above stretched the Scenic Cruise, a variation that avoided a 5.10 offwidth on the Cruise while adding a techy, pumpy 5.10+ dihedral and notorious 5.9 "Pegmatite Traverse" on slopers to join the Cruise at pitch six.

Earlier, Wiggins had told his friend Stewart Green, a climber and photographer, about his plan and asked if he could shoot the ascent. Green, who was already booked, says, "I thought it was the craziest thing I'd ever heard." He didn't try to dissuade Wiggins, though. "You didn't talk Earl out of anything."

Wiggins had practiced by climbing the Cruise with partners at least two or three times. He'd climbed the new Scenic Cruise once, with his friend Dan McClure.

Jeff Achey in Climb! The History of Rock Climbing in Colorado, would write, "This ascent was the longest, hardest, and boldest free solo then done anywhere in the world."

Of the actual event, Wiggins said little. Green recalls, "He told me that it went well with no problems. He was understated about the whole deal and modest."

The feat places Wiggins in the pantheon of the solo greats Henry Barber, Peter Croft, John Bachar, Derek Hersey, and Alex Honnold.

***

Outside of his community, Wiggins was only sporadically known, mainly through cliffside tales of a skinny, unassuming unknown with thick glasses who'd "done everything." In Colorado Springs, Wiggins established dozens of hard trad routes up to stout 5.11, with an estimated 200 to 300 FAs overall including those in the Black Canyon, South Platte and Utah desert. He and Dunn tore up the Black with one-day free ascents of various Grade IVs and Vs, such as the hideously protected Diagonal in October 1976. A month later in Indian Creek, Utah, as friends watched in fear that the pro--hexes--would never hold a fall, Wiggins fired the laser line of Supercrack (5.10), genesis of desert free climbing. In November 1977, in the Black, he and Bryan Becker forged up the Nose (VI 5.10 A5), then the hardest big-wall climb in Colorado.

Outside of climbing, the mechanically adroit Wiggins became one of Hollywood's most in-demand riggers: a professional profile lists 45 films and shows and two IMAX movies, his career boosted by the 1993 blockbuster "Cliffhanger," filmed in the Dolomites. Among his survival stories is one from that site, when a violent storm blew in. Wiggins was hit by lightning, thrown off the top of a 1,000-tower onto a ledge, and there juiced several more times.

Wiggins died in December 15 years ago, by his own hand in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Much is unknown about the highs and lows he experienced, the losses and disappointments he endured, and the nature of a kind, questing and troubled person who found his true self--in a way that must have seemed a miracle--in climbing.

Green was, he says, "astounded" upon his friend's death.

"I just couldn't believe it. But you never know what's going on in people's lives. Jimmie and I talked about it for years: Why didn't he call us? Why didn't he call his friends? ... We were all willing to help, to do whatever.

"We still don't know why he did it."

***

Christopher Earl Wiggins was the youngest of five children, preceded by Lou, born in 1949; Lynda, in 1950; Art, 1953; and Scott, 1955. Born August 24, 1957, Earl would have been 60 this year. He was 5-foot-11, a slim 150 to 160 pounds, with wide shoulders, sinewy forearms and flyaway brown hair.

The children grew up at 6,200 feet in Colorado Springs, a sprawling city that juxtaposes the progressive Colorado College community and conservative groups such as Focus on the Family, as well as three military bases. On one side the city opens to plains; and on the other, butts up into a whole lot of good climbing. Cliffs and boulders fill its parks.

His sister, Lynda, says with humor, "We were kind of feral kids." She remembers fun days horseback riding--the family owned horses--"and generally running around outside." Their home lay on the slope below the cliffs and ravines of Austin Bluffs and on the edge of plains where they could play and hike.

Lou, who had diabetes and epilepsy, died at 21. Lynda says, "Now looking back, we think he also had bipolar disorder, but I don't think people were diagnosing things like that then."

Lynda remembers Earl in his late teens or so being "down" for a week or longer. As an adult he was diagnosed as bipolar II, which has been in the family across three generations.

"I know that Earl had depression for a lot of his life," Green says, "even in the early days. He told me about it. But I never saw any outward sign that he struggled or was suicidal."

Earl, says Lynda, was "quiet, patient and incredibly kind. He loved animals, and animals loved him." Indeed his widow would later say of their two labradors, "He loved them so much I really thought they'd keep him on this planet."

His brother Art, now an electrician, describes Earl in boyhood as "shy, not athletic ... just a squirrelly little brother, always kind of cheery.

"Earl never really got into trouble. He was a good kid."

At 14 Earl started climbing, learning from a local named Bill Mummery.

From the start, the sport must have felt like a revelation. Art came along at Mummery's behest. Art says, "Earl was always a klutz. He never was in sports because he just really couldn't do it. I don't know what happened when Earl started climbing. He just really excelled. It was like, how is this possible? This kid can hardly walk."

While his brother was at first timid and physically unsure on rock, Art says, "He was sure he wanted to do it. So he kept working on it."

"He didn't have self-confidence until he started climbing," says Lynda, "and climbing changed his life."

Their father was a prominent area physician, a heart and lung specialist. Art calls the parents "really strict but really caring."

The brothers climbed for years, with Earl the driving force but Art a game partner: "We went climbing all the time," he says. "Hoosier Pass. Telluride, Vail, Rigid Designator, Bridalveil Falls. He led all that, in his late teens or young 20s.

"I was always worried because he seemed to have no fear. I was with him on a route in the Black"--the 1,500-foot 5.10+ Kachina Wings--"when he took [a] screamer and broke his wrist. He finished leading it. He had to. I couldn't have!" Art laughs recalling his brother trying some new ice-climbing techniques during a night climb of the local Seven Falls, falling 15 or 20 feet into a pool, breaking through and falling behind the next set of falls.

He calls his brother overall "really happy" when climbing. "He made everybody feel comfortable. He was just in such a good place that everything was good all the time ... out there with the rocks and camping and everything." When they endured storms or other hardships, Earl would say, "You knew you were there."

Art says, "He'd say it all the time."

***

In Colorado Springs this year, Stewart Green sits in his breezy front-porch "office." A computer occupies a square table viewing a boulevard of open verandas and blooming fruit trees and, 12 miles beyond, the 14,115-foot Pike's Peak. Wind chimes tinkle in the backyard, and whiffs of lilacs and wood smoke waft through. Jimmie Dunn, another mentor to Earl, arrives.

They describe how Earl grew strong, especially in crack climbing.

"If he could get his fingers in, he stuck," Dunn declares. Yet far stronger were the youth's mind and will.

Dunn describes how, in the spring of 1975, in what is now called Grandstaff Canyon, near Moab, he belayed as Earl, 17, led 80 feet up a 5.10+ FA without being able to place gear (cams were not yet available). His feet were torqued in the crack, but the bottom one kept slipping.

Dunn says, "I kept yelling, 'Earl, stop that!'"

From above, only silence. Earl simply moved on and on and reached a ledge. "Earl never fell when the stakes were high," Dunn has written. At such times he had a rare ability to subvert fear and climb even better.

That was the trip on which Earl decided to hitchhike to Yosemite, and asked his climbing friend and classmate John Sherwood, who had come with him, to return the Wiggins' family car. As Lynda later said in a eulogy, John found himself in "the unenviable [position] of telling my parents that Earl was going to Yosemite ... instead of finishing high school." Earl phoned, and as his mother later wrote in her "Life Book": "We agreed that if he could make a living, it would be OK with us."

Earl had visited the Valley the year before, at 16. That visit he climbed Reed's Direct (5.9) with Mark Chapman, 19, who had the previous month soloed the first pitch of Outer Limits, then probably the hardest solo in the Valley.

In Yosemite in 1975, Earl slept under a picnic table--and soloed Outer Limits (5.10, 5.10) the day after whipping 30 feet off the crux traverse.

Chapman says that soloing the second pitch, with its slick 15-foot seam-crack traverse on smeary feet, "certainly set the bar higher" in Yosemite. Jim Bridwell, Valley denizen, later told Dunn he turned away as Earl embarked upon it. He knew its difficulty.

Earl that time appears to have overcommitted, and afterward told Dunn he'd stuck a finger through a piton on the traverse.

"Like, stayed there a while," Dunn says. "Maybe he couldn't get back ... maybe if he could have, he would have."

***

In November 1976, at 19, Wiggins slung on a rack of Hexentrics below a black parallel-sided hand-to-fist crack on a soaring Wingate panel in Indian Creek.

With him were his friend Bryan Becker, belaying; Green, with a camera and Super 8; Mike Gardner, with a Super 8; Dunn, Webster, Dennis Jackson and Cheryl Montgomery, Earl's girlfriend, whom he would wed in June, two months before turning 20.

In an unpublished manuscript, Green recounts the ascent as planned to catch the warmth of the early-afternoon sun. That morning, Green relates, Earl and Cheryl scrambled up to an Anasazi ruin in a nearby canyon, where Earl meditated; then everyone went bouldering, and several (not Wiggins) partook of hits of acid. Moving from boulder to boulder, Wiggins chatted about the beautiful weather while doing each problem easily.

"You seem to have it today, Earl," said Becker, as recorded by Green.

"Feel good today," Wiggins replied. "Today's the day."

He racked up amid discussion and excitement, and donned a celebratory, even ceremonial, Hawaiian silk shirt. In the film "Luxury Liner," Becker recalls Wiggins saying, "Might as well put on a nice shirt today, could be my last day."

Wiggins climbed steadily, even fast. Aside from a directional off the belay, he put in only four hexes in 85 feet, none in the last 25 feet. While some accounts have him climbing out of control 80 feet up, Green says Earl remained cool and precise.

Wiggins' route name, Luxury Liner, never stuck, and the climb became known as Supercrack of the Desert, and later just Supercrack.

***

Back home at Turkey Tail, a granite crag in the South Platte, some 40 miles from Colorado Springs, Wiggins soloed Whimsical Dreams (5.11), sustained and reachy, with two 5.11 sections and a 5.10 roof. He soloed local 5.9s and 5.9+'s multiple times, and at age 15 or 16, the loose Scarecrow (5.10b) in the Garden of the Gods, a soft sandstone cragging area in his hometown. Wiggins soloed often enough that his friends took to saying, when climbing ropeless, that they were "on the Earl."

Years later, as Green and Wiggins, by then in his 40s, replaced hardware in the Garden of the Gods, Green asked his companion why he had soloed all of those routes.

"I wanted to make a name for myself," Wiggins said. "I know it was kind of a stupid thing to do, but that's why." He said he had been "a dumb kid."

Green perceives a dichotomy in Wiggins' character: "Like a lot of people he wanted some respect for the things he did. He wanted a certain amount of fame, but he also valued his privacy" and did many FAs without reporting or even naming them. In his 30s, he co-wrote a seminal book documenting Utah desert climbs, but largely stayed out of it.

In any case, Green says, "When you watched Earl solo a climb, he was solid. I never saw him shaking or thought he was going to fall."

***

Bryan Becker, interviewed below his backyard pear and apple trees on a steep hill in Manitou Springs, halfway along the pathway from Colorado Springs to Pike's Peak, immediately invokes Earl's humor.

"He had those Coke-bottle glasses but you could see his mouth grinning underneath them. When we were climbing the Nose [in the Black Canyon], he'd say, 'I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore!' We'd just yell it to ease the tension and laugh."

He also describes a steeliness. "We got down to the bottom of the canyon, and I'd forgotten my raingear. Earl insisted I go back up to the car and get my raingear. This was after we'd been bouldering naked. And probably smoking." He mimes.

"He was serious about being successful. He wanted us to have every chance. He didn't want to turn around." Wiggins ultimately led them up the thinly protected pitches.

"Especially when we were young like then, it was just fun hanging out with him. Though he did like being in charge a little. I'd say, 'Let's do it your way, Earl.' That's why I went up and fetched my raingear out of the car. That's 2,000 feet. After just descending it."

At 20, Becker was rope-soloing D1 on the Diamond, Long's Peak, when Wiggins (guiding the peak) "came and poked his head over and checked on me to make sure I was O.K. ... That was very reassuring to me. He had that considerate streak." Whenever Becker did a hard climb or ski descent, Wiggins was the first to call with congratulations.

***

On December 21, 1980, Cheryl Wiggins was killed in an unroped plummet while full-moon climbing on an icefall above Colorado Springs. The event was a major trauma for Earl, though the two were separated.

Two years later he married Virginia Savage (the marriage was brief) and moved to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where he worked building high-tension power lines and climbed ice and mixed routes in the Tetons. A local, Steve Shea, has posted, "Probably most saw him as a great rock climber. He was a very good alpinist as well ... fast and solid on mixed and ice."

Art brings up a little-known aspect of Earl's trajectory: He wanted to proceed to the greater ranges.

In 1983 Earl and Jeff Lowe traveled to Nepal to try new routes in winter on Pumori and Nuptse. As recounted by Lowe in an article on Supertopo, on the first night at their 17,000-foot base camp, Wiggins sustained severe pulmonary edema and had to be taken 3,000 feet down to Pheriche for oxygen at a tiny hospital, then on by yak to 9,000 feet.

The plan was for Earl to recuperate there for five or six days. In the interim, Lowe, concerned that the driven Wiggins would return early and push to go higher, left to solo an established route. When he staggered back into base three days later, he found a note:

"Hey, Jello,

"I felt good, so I came back up sooner than we planned. I watched through binoculars as you reached the summit yesterday. Congratulations! ... I'm going to head up today and try to do the [new] route we originally planned to climb."

Lowe was aghast, but, beyond exhausted and with darkness near, felt helpless. He sank into sleep, then was startled awake by one word, "Help."

"The cry had not been loud," he writes. "In fact it seemed to have originated inside my head .... One thing was certain, though--it was Earl's voice."

Wiggins was bivied somewhere a mile above. Lowe roused their three Sherpas and headed off, searching, finally spotting a faint headlamp beam. He found Wiggins on the ground, a "frothy substance drooling from the corner of his mouth and making a dinner-plate size puddle freezing around his cheek."

Lowe writes that as he knelt, Wiggins whispered "the best joke I have ever heard: 'What took you so long?'"

He was again carried down.

Art says his resolute brother's inability at altitude "crushed him."

"He said he couldn't do it, the mountaineering thing. That was what he had next on his agenda."

Prior to Nepal, Wiggins had begun seeing Katy Cassidy, of Boulder, a strong climber and imaginative character with whom he had an important relationship of seven years. In December of 1984 he fell and broke both ankles on the multipitch ice route Stairway to Heaven in Provo Canyon, Utah. His partner, the leading alpinist Mugs Stump, carried him down (and brought him Christmas presents in the hospital).

In a wheelchair, Wiggins audited a college class (Chinese history or philosophy, according to his sister), though not to its end.

Lynda, who like him is adventurous and peripatetic, says, "He could not stand to be bored. He absolutely hated it, and he got bored very easily. He was one of the most well-read and informed people I knew. He just couldn't bear school."

For the rest of the 1980s, Wiggins and Cassidy traveled the country working on power lines and climbing. They spent a cumulative eight or nine months in the Utah desert and climbed many bold and beautiful routes and towers. They and Art put up the 750-foot Road Kill (IV 5.9 A4) in the Fisher Towers, with other FAs there and in Indian Creek.

Green says Wiggins and Cassidy "were a really good climbing team. ... I think that was probably a good time in Earl's life."

Cassidy, now a massage therapist in Longmont, says, "We had a lot of fun. We climbed a lot, roller bladed, played blade hockey. One windy day, on the blades, we held a tarp between us, like a sail." She calls Wiggins capable and thoughtful. "He would talk to anybody," she says. "He didn't have any airs." They spent much time with Art; Cassidy says a "defining" aspect of Earl's character "was his love for his family."

In 1990 the two published Canyon Country Climbs, brimming with photos, history and tales of a productive period shared with great explorers such as Kyle Copeland and Charlie Fowler. Dedicated to both sets of the authors' parents, the book includes photos and writing by many climbers.

Earl emerges as a careful and respectful observer, describing the land, mosses, fungi, seeds and flowers as well as the "orderly layering of sandstone sediments ...[that] follows the rise and fall of geologic uplifts and faults" and the "cascading bowls of rock [that] pour into one another, draining the landscape above."

Aside from a shot of the coauthors (and their cat), the book contains only a few distant shots of him, unidentified, and nothing on Supercrack.

***

Rigging work on "Cliffhanger" in 1992 led to "The River Wild" in 1993, and Wiggins founded Wiggins Aerial Rigging, becoming busy with commercial work. In the autumn of 1994, he asked Mark Chapman on a shoot in Yosemite that proceeded to Moab.

Chapman says, "He taught me a lot and gave me a lot of work," with jobs on the 1996 "First Wives Club," where they rigged a scene of women on scaffolding plunging down a skyscraper, and two Batman films.

After "Batman & Robin," feeling burned out (he spent 300 days on the road in a year), Wiggins sold his gear and began selling real estate in Colorado Springs with Dawn Doucette, whom he married in 1996.

After a year in that sedate life, however, he wanted to return to film. In 1999, when Yosemite's Ron Kauk was tapped for climbing stunt work in "Mission Impossible II" and asked for Chapman and Wiggins to rig, Wiggins had already returned to L.A., bringing Doucette and starting anew. During that job he approached Chapman about a partnership.

"He had an idea to make a couple of winches operated by motion-control software," Chapman says. "I tip my hat to him. It was a good idea."

Chapman says that, using his real-estate assets as collateral for a line of credit, he "ponied up close to $100 grand" in two installments. They bought back some of Wiggins' old equipment and purchased some new gear, software, a precision winch, and then a second winch to work on "A.I.: Artificial Intelligence."

Chapman says Wiggins was challenging to work with--"He was an intense guy and he could yell, he could scream"--but that for a long time they remained friends. He recalls a day when Wiggins berated him and called later to apologize and say Chapman had been correct.

Wiggins' sister calls Earl a lifelong perfectionist, and says that at work he would have been "a stressed perfectionist." He was also drinking heavily (a large percentage of bipolar patients attempt to self-medicate).

Chapman calls what was to ensue "a sad, complicated thing," and also that he felt the "complex" Wiggins grew somewhat paranoid. "In a nutshell, he essentially tried to push me out of the picture," he says, beginning with leaving him out of jobs. "I eventually sued him."

***

Doucette was part of the small Colorado Springs climbing community. A mother of four, seven years older than Earl, she was the former wife of the longtime climber Don Doucette and had been a close friend of Cheryl Wiggins. She and Earl had known each other for 17 years, and, in what Lynda in her eulogy called a "rich and mutually creative relationship," were to be together a decade. The couple lived only half a mile from Earl's parents, Milton and Mary Ellen, and for a time saw them often.

Doucette is petite ("five-foot three-ish") and fine-boned, with a mellifluous voice. She lives in the Springs, on the third floor of a friend's Victorian in a stately old neighborhood.

She believes Earl suffered from depression most of his life. Early in the relationship, he had tried warning her, "You don't want to be with me. I have black moods."

Wiggins was also lighthearted and silly: A lifelong practical joker, he hid her harness when they went climbing in Eldorado Canyon, and later positioned a life-size Chewbacca cutout in their house where she'd come around a corner.

Once her daughter, hearing them from another room, remarked, "You guys laugh so much."

Of Earl's moods, she says, "He managed to keep a tight grip for the most part. The irritability, I think, came out more when he was running a film crew." She acknowledges tension, however, in managing a household with children: "He had never been a parent."

When stressed at home, he would grow quiet. "He was afraid if he blew, it would be a major eruption," she says, adding with feeling, "It must have taken so much energy."

In late 1998 the couple moved to Santa Clarita, California, about 30 miles from Hollywood.

Over the rigging years, Earl's relationship with family deteriorated. Doucette recalls a painful visit home in 2001: "His mother had loaned us some money to invest in our equipment for the aerial rigging, and as agreed we were paying her back monthly. Earl was feeling pretty good because he had done some producing on a MacGillivray Freeman film, on caves, and he wanted to make a trip here and to really just spend time with his parents. He was just so hoping to come home and make a nice connection, and it all went very awry, and it took me awhile to piece it together."

The mother at some point became agitated, Doucette says, and accused the son of using the house as a hotel. "When we got home there was a letter from his father apologizing on his mother's behalf but kind of defending her, and so Earl was hurt."

He perceived a lack of support and ceased contact.

She continues, "Father's Day rolled around [June 17] and Earl--in his own words, in his 'pig-headed stubbornness'--chose not to call." Dr. Wiggins died the next day at his own hand.

His health was a leading factor. "He knew he was on the way," says Art. "He was 78. He had emphysema"--with very labored breathing. "He loved to hike. He just couldn't do it anymore. He had had a heart attack. Being a medical person, he knew."

"Of course Earl was terribly guilt-ridden," Doucette says. "That was the beginning of the end for him. He went into a really, really deep depression."

Lynda Wiggins confirms it. "When my father died ... [Earl] started to take a dive. He was a different person than he had been all of his climbing life." Milton and Earl had always been close, and Milton very supportive.

Of Earl's eventual death, Art says, "I was not really shocked. He was getting really paranoid about the family, that everybody was against him. I thought he was way overextended in his finances.

"He wasn't climbing, he wasn't mountaineering, he was rigging, and that came with stress and deadlines and managing people. He'd had enough."

***

In spring of 2002, Earl and Doucette moved to Lake Oswego. She had never liked So Cal and says by then Earl was ready to leave. The area had never felt like home, and he spent little time there anyway.

She also says that though he agreed to seek help and accept medication, he was convinced he could not be helped. In the autumn of 2001, while still in California, he had disappeared for a day.

"I could not get in touch with him, and he later told me he had driven out to one of the nearby canyons and put a gun in his mouth."

In summer of 2002 he left for a job in Hawaii and discontinued the medication, though she pleaded otherwise.

He had told her that, on meds, "I don't feel like myself." (He similarly told Green they "took the edge off.")

"I really think the main reason was that he didn't like being emotionally level," Doucette says. "He missed the mania." When he was up, she says, "he could work incredibly long hours, he could go days without sleep, he could do long climbs."

Upon his return, he told his wife, by her account, "I don't feel suicidal, and I promise you if I ever do we will revisit the medication issue."

"So [his death] was a shock for me," she says. "I did not see it coming."

She believes his frequent work trips helped him mask his depression. She also feels his history of travel and changing locations likely offset it through new stimulation and distraction.

In a letter to a climber-rigger friend, Perry Beckham of Squamish, B.C., after returning home from "Cliffhanger," Wiggins wrote of already having "itchy feet. Just want to be on the move."

Doucette says, "I always felt like he was trying to outrun himself. The irony was that he loved being in Oregon, and we were getting out and doing a lot of fun hiking because it was all new territory."

As to his climbing, she feels, he likely "pushed the envelope because it was O.K. if he died. My impression was he didn't care. He didn't have a death wish, but he was O.K. if something happened."

***

At Thanksgiving 2002 he returned to Oregon from a job in what Doucette recalls as a "cranky and critical" state. On December 24 he arrived again, for the holidays, from California. At that time the couple discussed some issues his wife prefers to keep private beyond saying, "I put the ball squarely in his court." On the 27th, they played Ping-Pong, they laughed; they watched a Robin Williams movie, "Dead Poets' Society."

Doucette, who has since worked as a private grief counselor, says, "We were sitting on the couch together, and after the movie he took my hand, and he said, 'I want you to know you're the best thing that ever happened to me.'

"And he chose to sleep in the downstairs bedroom because he knew what he was planning."

At perhaps 2 a.m., she heard him come up to the kitchen and plunk ice into a glass. He had been drinking vodka on the rocks that evening. The next day the glass was on his nightstand.

In the morning she sat at the dining-room table reading a self-help book she thought might help him, then walked the dogs. Returning at about 10 a.m., she saw that the coffee pot was untouched. "That was cause for some alarm," she says: Earl didn't sleep late.

She started downstairs and smelled something acrid, later understood to be gunpowder. She called Earl's name and tried to open the door, but he'd blocked it.

"I shouldered in, then I found him ... and I had to let him go."

Wiggins was 45.

***

Consider many factors and increments. Wiggins suffered from mental-health issues. He had lost his brother, father and a long list of friends and fellow climbers from Cheryl Wiggins to Kyle Copeland and Mugs Stump to accidents or illness. He had stopped and resumed drinking, and termed himself an alcoholic. His suicide note listed his deteriorating eyesight, which affected his work; diminishing fitness and chronic back pain; dismay in his job and erratic income; and the boredom that plagued him.

His work life was high pressure, involving risk-management, hectic schedules and long hours away from normal life. Lynda says, "Regular sleeping habits alone can help ward off the effects of bipolar disorder." Routine does as well, yet he avoided that.

Chapman, who describes himself as "very conflicted" over events, says the death came in the middle of the lawsuit, and that he wondered if it was a tipping point. He settled out of court "and walked away."

"I did feel he had a legitimate claim," Doucette says. "He settled for much less than he had originally asked for, and I was grateful."

Chapman later shared in two Academy Awards, a Technical Achievement Award in 2006 and a Scientific and Engineering Award in 2011, both for development of technology, and says, "I always felt like Earl would have, too. Earl's idea to build computer-controlled winches was at the heart of this technology. When Earl approached me with the concept in 1998, no one had anything like it."

Like many suicide victims, Earl believed himself a burden.

"Because of the love I feel for you," he wrote Doucette in his note, "I am saddened ... that you share your life with such depression as I carry."

He castigated himself in his relationships, but the heart of the passage was his sense that he simply could not go on. "There is no more drive," he wrote. "I have lost it all. For over a year, I have thought of suicide every day. The depression comes or goes but never leaves. ... Our happiest moments of the last several months have been overshadowed by the knowing it shall return."

By hand below the typed note, he wrote, "Finally, I find peace."

***

Earl for years wrote letters home from the wilds that described beauty and hardships and ended, "Loving every minute" or "Loving life." Lynda at his service said, "He had an intense passion for life which, for reasons we will never fully understand, failed him in the end. But until that time, his excitement infused almost everything he did."

Katy Cassidy, in an honest, loving eulogy in Alpinist, wrote, "[H]e was very intelligent, very sensitive, kind-hearted, generous, an imp, an asshole, a lover." Upon the shock of his death, she says, she could not cry for months; then could not stop crying for months.

John Middendorf, who worked two rigging jobs with Wiggins, calls him "a legend both in climbing and in rigging. So mellow, but also so intense."

Lynda says, "I don't want people to think he was taking risks because of this illness. I feel like it diminishes his climbing to have it chalked up to that. I do think that climbing took care of his problems for years until it caught up with him once he had that rigging business. He was so depressed. It's hard to know what caused it--the depression--and what the depression caused." Wiggins once told Doucette that he had never thought he wanted to grow old, yet wanted to do so together. Asked if climbing also kept him alive longer than otherwise, she says, "Absolutely."

Climbing gave him joy and focus, but he gifted it as well, with his creativity and presence. Dan McClure says Wiggins brought out new levels of strength and courage in his partners.

Says McClure, "Saying, 'Miss you, Earl,' doesn't do justice to how I feel."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.