Dapper Dan Is Ready to Move Beyond Logos

Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day’s story is still being written. The 74-year-old style icon’s autobiography Dapper Dan: Made in Harlem dropped earlier this month, but he isn’t slowing down post-memoir. With a thriving uptown atelier, an ongoing partnership with luxury giant Gucci, and a biopic in development at Sony, his reach has never been wider, and he’s eager to harness that power.

“The new guys are giving me new tools,” he shared during a visit to the Vogue offices. “It’s the same as when I was coming up with the best hustlers from the South who came from the great migration. Now I have people who have achieved great goals in fashion and literature who have an interest in me. So I’m absorbing all of that—I can’t wait to get out of this room and go do things!”

Made in Harlem charts Day’s rise from the tenements of 1940s New York to the highest echelons of the luxury industry. The book reflects on his many incarnations with plenty of pit stops and plot twists along the way. Long before he made his mark with clothes, Day was hustling and penning essays on Pan-Africanism in the pages of the progressive publication Forty Acres and a Mule and undergoing a personal awakening that would lead him to create his now-famous haberdashery on 125th street. “I was fortunate. The spiritual journey that I was on, when I found fashion, and the transformative thing that it did for me,” he says. “There’s something for everybody out there if you’ve got the story, and I became a good storyteller.”

An experienced narrator Day shares pithy anecdotes and uncomfortable truths with ease. Nothing—be it drug use or being busted by Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor—is off-limits, but some portions proved harder to write than others. “The most difficult part was telling my family story. Reflecting our relationship, especially with the boys—the trials and tribulations,” he says eluding to the difficulties he and his brothers Cary and James faced as they struggled with heroin addiction. “My father was prepared for it, but my mother came up from a small town in the South, and god sustained her. So, to see her sons slip into destruction [was difficult]. Reflecting on that was the most painful part.”

Born into a Harlem primarily populated by African Americans who moved to New York to escape persecution in the Jim Crow South, he recalls learning at the feet of his neighborhood’s hustlers, men who refused to accept the hand they were dealt. Driven as a teenager, his goal was excellence—even when the undertaking wasn’t legal. “I realized early on that if I’m going to serve the low world, the hustlers, I’m going to be proficient,” he says of his early days running numbers and card scams. “Nobody is going to be better than me. So I went and bought all the books on John Scarne, who’s always a master at that. I took it beyond that. And then I went and changed the card game.”

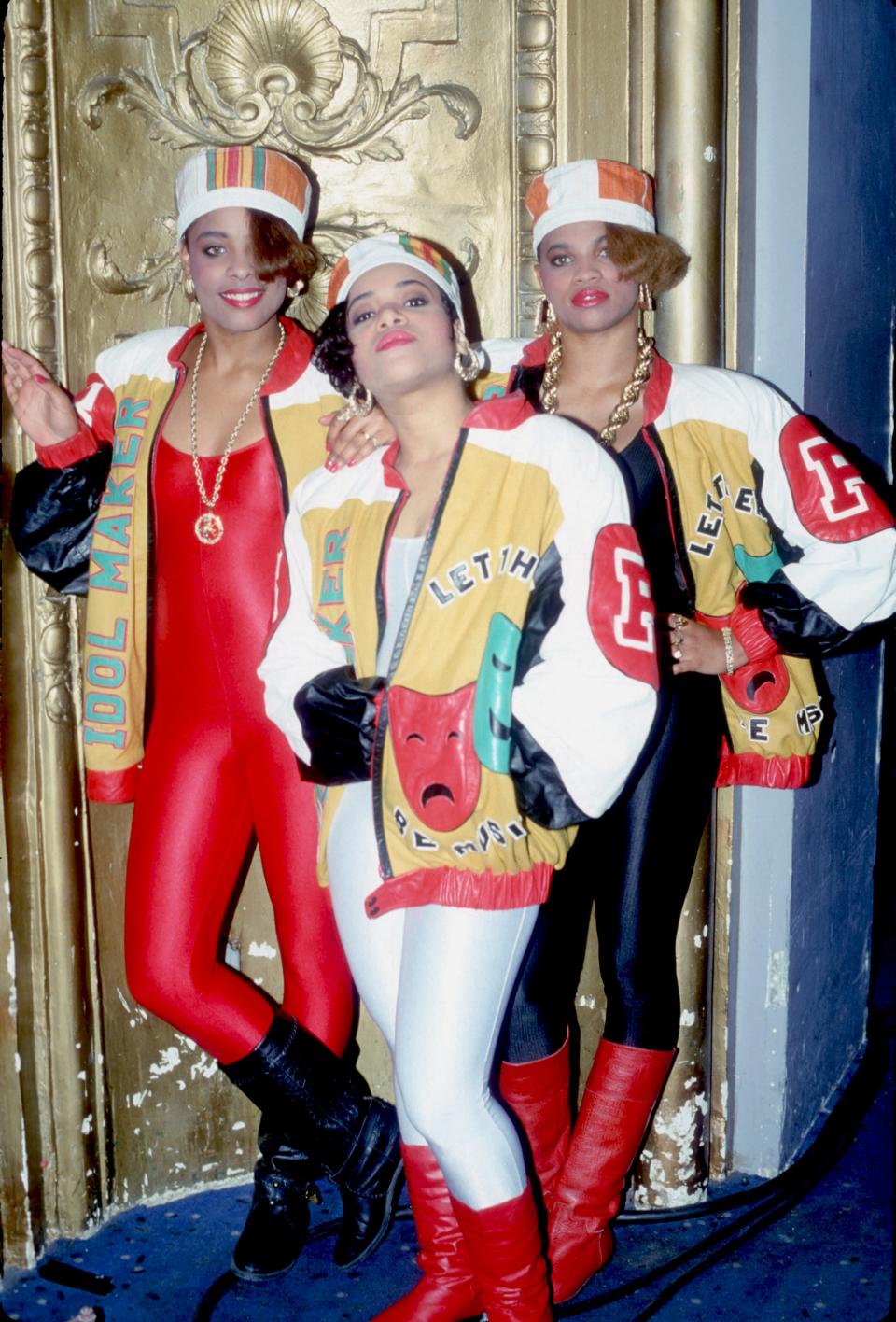

Innovation would become his signature. When wholesalers wouldn’t sell to his 125th Street boutique because of his skin color, he focused on making custom designs. When big brands weren’t attuned to the wants of an urban clientele, he stepped in to fill the void. “The biggest thing you can do is capture the culture,” he says, offering a few words of advice to his fashion successors. “If you can get ahead of it and try to, don’t try to turn it into somebody else’s culture, but bring something to it, like what I did with the rappers.” Indeed, it was through outfitting groundbreaking stars like LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa, and Jam Master Jay that Day was able to merge music and fashion into a singular style the defined hip-hop’s visual presence.

Eventually, the Dapper Dan look would come full circle. After years of his reimagining of the emblems of European brands, those very European brands started co-opting the logo-heavy swagger of his creative output. When Alessandro Michele put a puff-sleeved double-G-covered mink bomber on his Cruise 2018 runway, the internet called foul, but his was only the most direct homage. You need only look to the monogram in Riccardo Tisci’s Burberry debut or Supreme’s willingness to cover anything in red and white Futura Bold to understand the impact of Day’s worldview.

The Gucci situation led to an unprecedented collaboration. Day served as the face of the brand’s Spring 2018 menswear campaign and the force behind a series of special capsule collections, the first of which launched in July of 2018. But though the partnership has proved successful for both parties, it’s done little to stem criticism online. Unfazed by his detractors, Day is realistic about the impact that the backing of a corporation like Kering can have. “I’m seeing how people have responded to this, [how] they see this as a corporate oppressor, which goes back to the fact that they don’t understand,” he says. “The ones who are against this are practicing what I call Jim Crow economics. When you tell someone that we don’t need them, that we’re going to do it ourselves, you have no working idea of what culture is and how culture works. Do you think you can start from the bottom and catch up with this multinational global corporation? That’s so foolish.”

For Day, the partnership with Gucci has allowed him to expand his reach and the scope of his expression. The obstacles of the past—access to equipment and permission from copyright owners—no longer hinder his work. “[Before,] I couldn’t go to manufacturers and say, ‘this is the idea I have; I’m going to put it together, and this is how I want you to do it.’” I had to learn how to do things myself because I didn’t have permission from the manufacturers who own the trade world,” he says. “Now I can get all the machinery I want. I can explore the ideas that I want and tell all these stories.”

Though the logo-laden “knock-ups” he crafted for hip-hop’s elite still serve as a calling card, Day is now interested in symbolism beyond luxury iconography. As always, his work explores the black experience. A recent trip to Nigeria yielded a dynamic idea—using fashion to connect African American culture with that of the African continent. “I went this time [and] I said, ‘Now I have the platform; I can tell a story through symbolism that we both are connected to and find the string that runs between us,’” he says. “I’m going to the source, like I’ve always done, to extract something that connects us on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and can bring us together [to] create a platform of pride and dignity.”

His return to the source [Nigeria] revealed a host of issues—colorism and the $10 billion skin-bleaching industry among them—that he feels fashion can address. “Seventy percent of Nigerian women use skin cream lighteners, thirty percent of men. So what we have learned to embrace in certain ways here, they’re rejecting there,” he says. “The job is huge. I have heard scholars over here say we’re going to be responsible for changing the way people of color feel about themselves here in America, but I didn’t have any idea how critical it was there.”

Through the creation of design based around cultural commonalities and mutual respect, Day believes broader social change is possible. “There’s such a degree of people that don’t understand who or where they come from. If I could connect that and give value to who we are here, [then] create a platform for that value, we have reason to love and respect each other,” he says. “I see fashion as a revolution. A peaceful revolution that brings us all together.”

That focus informs his interest in totemic design. Ancient religious characters—call them the original logos—serve as a fixture within his most recent work. It’s an interest he’s nurtured for years, and it’s finally making its way into his clothing. “I knew the power of symbols from my spiritual experience, from studying the Ankh and the pyramids. The further you go back, if you want to understand the foundations of religion, it takes you into a world of symbols,” he says. “Now that I’m free to go out and gather symbols, I don’t need to borrow the FF [or] GG.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue