Dance Battle! Meet the Warring Milli Vanilli of Italo Disco

Close your eyes and turn on your inner synthesizers, the ones that teleport you to 1985; imagine yourself dancing—Fiorucci-clad, Peroni in hand—someplace dark and thumping and clouded with cigarette smoke, and then stumbling outside into a cobblestoned, chiaroscuroed alley. Tanned, Lurex-swaddled people you've never seen in your life are screaming buona notte as you almost trip over a Vespa kickstand. That's the Italo Disco vibe.

If you're familiar with the pop singer Den Harrow, which you probably aren't, you're likely Italian and approaching retirement age. Or you're American, maybe in your 20s, and into some pretty strange shit. For a few years in the mid-1980s, you couldn't enter a nightclub in Europe without hearing his spooky, soaring refrains. When said fast and often, his name was meant to evoke denaro. Money.

The singles—“Future Brain,” “Bad Boy,” “Don't Break My Heart,” “Catch the Fox”—beat out David Bowie on the charts, beat out Madonna, beat out Lionel Richie, beat out Wham! Den Harrow was everywhere in Europe during those years: Calabrian concerts, Bavarian discotheques, pouring out of Fiat car radios as they zoomed down the autostrada.

With Disney-blue eyes and doll-blond hair, Den Harrow looked like a cross between a young Leonardo DiCaprio and a Let's Dance-era Bowie. He was given to deconstructed crop tops and had a crow-like affinity for accessories: sweatbands, fingerless gloves, diamond-stud earrings, leather cuffs. He had a wacky stage presence and the physical stamina of a testosterone-soaked eighth-grade boy, pre-soccer practice but post-parking lot Mountain Dew. Teenage girls screamed at Sicilian music festivals; they stalked him in Ibiza. When journalists asked for his real name, Den Harrow told them it was “Manuel Carry.” When they asked where he was from, he told them Boston. But sometimes he added an inadvertent a to the end: Bostona. Everyone loved him; everyone believed him. The 30-year deception he's been half-maintaining ever since, and the insane, decades-long, continent-spanning feud it fuels, is where we pick up our story.

A few years ago, Jonathan Sutak, an American movie-trailer editor, found himself watching the video for “Bad Boy” in his Echo Park apartment in Los Angeles. It features a tightly edited selection of senselessly violent women dressed in Paleolithic rags. There's also a handmade-looking monster, clearly modeled after a pangolin; some torch-wielding *Ben-Hur-*style extras; broken glass; smoke everywhere; a few Harley-Davidsons; and a lot of frantic sprinting through a blue-lit industrial space. The whole thing is aesthetically off and conceptually confounding. It's like someone took decades' worth of American pop-cultural grammar, misunderstood all of it, never learned the context, reverently but anachronistically re-assembled the pieces, and then was like, “Here you go—enjoy!”

Though present in the opening shot, Den Harrow himself—built, bronzed, all pale eyes and dark lashes—doesn't actually start singing until a quarter of the way into the four-and-a-half-minute video. And when he does, the atmospheric weirdness gets…weirder. How can I remember what girl I will see today / If tomorrow she'll be gone? / Now I'm a pretender in a special kind of way. Den Harrow's voice sounds uncanny and echoey and somehow too deep for a man with such an outrageously pretty face.

But maybe I only think that because I know the story now.

20120223_zaf_z19_572.jpg

Jonny Sutak, 32, hadn't thought about Den Harrow, not really, at least, for almost two decades, not since he was a 13-year-old Jadakiss fan in brownstone Brooklyn—a scrawny kid with a fade, a burgeoning weed habit, and a brand-new set of turntables (bought with bar mitzvah money). He spent his after-school hours fucking around with records from his dad's seemingly endless collection. Most of them, admittedly, were instrumental film scores from the '70s and '80s, so he was psyched to find the “Bad Boy” single tucked amidst all the John Williams and Ennio Morricone. He liked the song's lack of subtlety, its powerful drums, the way the synth layers went up the scale in this perfectly pop way. He was surprised that the lyrics were in English, and he found them, well, sick:

There are blondes and brunettes just like different cigarettes

All their lips are burning hot

Some dress “Valentino”

Others wear T-shirts to show

What a shapely bust they've got

Fifteen years later, having just cut the trailers for both the fifth Transformers movie and Logan, Jonny—tired, bored, a little nostalgic—went on YouTube, and in that aimless, memory-excavating way you do when no better alternative immediately comes to mind, shot himself, only half purposefully, back into the past. The saccharine chord progression was delightfully familiar, and there was Den Harrow! There he was! Running through that creepy, azure, GDR-looking warehouse. As the video came to an end, Jonny noticed, on the right-hand side of the page, something else: another video, uploaded on October 25, 2010, titled “Tom Hooker responds to Den Harrow's threats.”

“Who the hell's Tom Hooker?” Jonny thought. He pressed “play.”

“Hi, I'm Tom Hooker,” says the guy on the left, smiling into the camera. “Hi, everybody,” adds the guy on the right, in heavily accented English. “I'm Miki Chieregato.” Then Tom Hooker starts speaking.

“I am here to tell you something that has never been officially declared before,” he begins, and then goes on to explain that he recently joined Facebook and “in less than a year I got over 2,500 friends,” one of whom was Den Harrow. “And this,” Tom says, “is where I found out that Stefano Zandri—that's his real name—was telling people that he was the real singer.” Tom plays three clips of Stefano performing over the years, as evidence of his lip-syncing. They end, and we go back to the ad hoc conference room. Here, lights (blatantly added in post-production) flash, paparazzi-style. “So I'm here to tell you the truth. I'm here today to tell you that I am the singer of all Den Harrow's greatest hits.… And I can prove it to you, right now, by singing a cappella.” Tom inhales theatrically and begins to sing—quite beautifully—for 20 seconds.

Stockin' away all the details you want to know

Day after day all your memories get to grow

Putting all that you've stolen

In a prison that you've locked forever

“I never really wanted to go public with this,” Tom says, sighing. “If Den was really nice about it, this day would have never come. But there is a thing called karma. After I left him alone for 25 years, I have received hate mail from his loyal fans, who don't realize that he is lying to them every single day. And this is not right. Because I'm telling the truth, and they don't want to hear it. I have never asked [for] or taken any money from his performances, but I want to declare today that he does not have my permission or authorization to use my voice anymore. On TV or in shows… This charade has been going on for a quarter of a century.” Tom goes on for several more minutes—listing the prizes that Stefano has won and kept, reading aloud from the Wikipedia entry for Milli Vanilli, recounting specific threats. “Enough is enough,” he concludes. “I've said what I have to say.”

Jonny was shocked. It was almost too good to be true. An intellectual-property dispute between two people who, for decades, everyone assumed were one? A pair of aging pop stars who, in trying to protect their individual legacies, were in fact collaborating in mutual destruction? An ontological treatise on fame and art and authenticity being co-written, spitefully, in real time, on Facebook? It was like Spinal Tap meets Shakespeare meets Cory Arcangel. Or something.

Jonny watched the video again. And then again. And then a few days later, once more. And it gave him this crazy idea. What if he, Jonathan Sutak, acting in a spirit of American interventionism, could reconcile Tom and Stefano—yoke, once again, the voice and the face that together had made such beautiful, meaningful schlock at the peak of their careers; foster, finally, after so many turbulent years, a sense of social harmony and maybe even economic growth? It wouldn't be his sole aim, but it was a good conceit. And anyway, after years of feuding, wasn't it time for the Den Harrow story to close the loop and end in peace? What if he made a documentary about it? And what if the making of that documentary was the thing that reconciled them? Okay, it probably wouldn't work. But maybe it could? And if his exceptionalism proved successful, it would be so worth it! The ultimate act of pop-detritus nation building!

Watch:

Announcing a Whole New Era at GQ

And so Jonny set about on his Marshall Plan-like quest. He cut back on trailer work at what was arguably the peak of his success, moved some money around, bought a camera. He went to Las Vegas and Milan and backwater Germany; he met obsessive fans and nostalgic nightclub owners. It took him years. He hired a cinematographer and filmed the whole thing.

To understand the extent of what he found, you have to start at the beginning of Den Harrow, the creation myth, and the context in which it was hatched. From the outset, the original producers of Italo Disco conceived of the genre as an export good made with import products, namely English-language vocals, whose repetitive lyrics, often accented and malaprop-laden, were set to catchy melodies filigreed with synthesizers. With their kitschy affectations, there's something almost primitively appealing about the best Italo Disco songs, whose supposed antidepressant effects were even the subject of an (inconclusive) psychological study. Decades later, the genre, which is often referred to, pejoratively, as “spaghetti dance,” is looked back on by Italians with a kind of condescending affection. In The History of Italo Disco, the DJ turned music critic Francesco Catalo Verrina wrote that for many years Italians were “almost ashamed to have been part of this movement and to have lived in that environment.” One of the more famous Italo Disco producers once regretfully rued that he had helped to “put the mustache to the Mona Lisa.”

Tom has a loving family, a beautiful home, a creative career, and lots of money. He also has a mortal enemy.

Stefano was discovered in 1983, at the age of 21, by Miki Chieregato, along with the producer Roberto Turatti, who saw him dancing wildly in a nightclub and thought he'd make a charismatic face for a new pop act they were concocting. They brought him into the studio but quickly realized he couldn't sing well with an American accent. He was handsome and naive, though, with a libidinous energy and seemingly zero stage fright. He'd do just fine. They already had a guy who could sing, anyway. His name was Tom Hooker, and he was American. He could actually write pretty good songs, and he didn't seem to hate the idea of another guy mouthing the words to them. For a few years, everything was great. Stefano and Tom weren't friends—they didn't eat dinner together or go to the movies—but they both understood their respective roles and maintained a professional rapport. They did what they were supposed to do. Tom, a Connecticut-born scion of a beverage conglomerate, grew up in Geneva and, pre-Den Harrow, had a solo career of his own, touring mostly through Italian hill towns. For Stefano, though, Den Harrow was everything. He didn't have a globe-trotting past—or a trust fund. And in 1987, when Tom got it in his head that he wanted to perform one of his songs himself—just one!—the producers said no. Are you crazy? they said. And ruin the entire illusion? For what? Because you, Tom, think it would be fun*? No way.*

Tom, sick of all this shit, moved back to America and backed away from the music industry. He got married, bought a house, adopted two kids. Stefano remained in Italy. Without Tom's voice singing new songs, he could only perform the old ones, which he did, over the years, in increasingly down-market venues. He claims to have moved to San Diego for a few years, where he worked as a bouncer at Planet Hollywood and as a personal trainer; then he returned to Italy, where he made tabloid headlines for crying on reality TV. He didn't have any money but was too recognizable to get regular work, so he continued to tour, lip-syncing to audiences of aging fans.

For years and years, the lives of Tom and Stefano remained separate. But when people started rooting around on Facebook, that's when their shared past came back to haunt them both. The person who sang felt used by the person who danced; the person who danced felt usurped by the person who sang. A pop-culture conflict that for decades remained latent in Italy was suddenly, thanks to social media and the pent-up rage of two middle-aged men, tabloid gossip. Fans were distraught. Some felt betrayed by Stefano, for lying all that time; others hated Tom for sullying an otherwise pristine myth that they would have been all too happy to continue believing in. Jonny got it all on tape, and now, three years after setting out, he was ready to show the world.

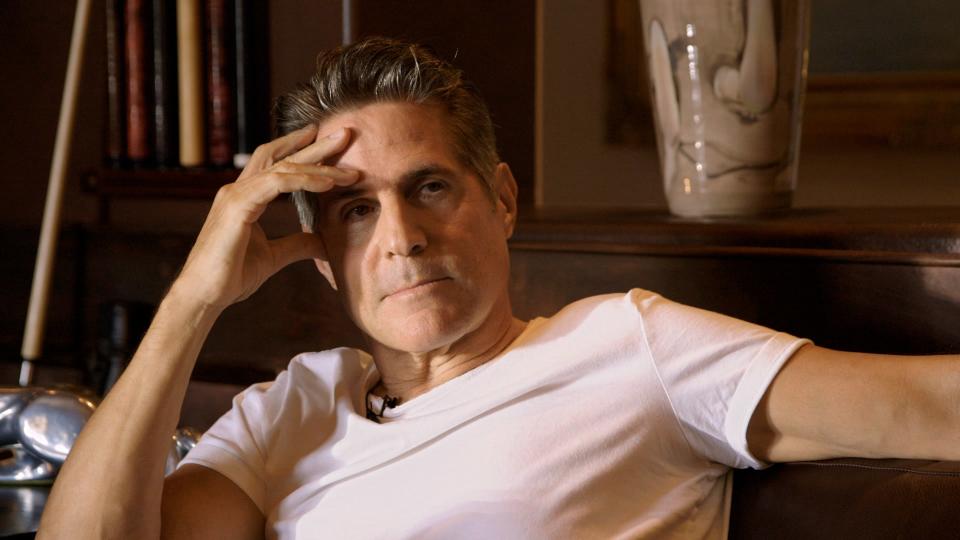

Tom Hooker lives with his wife and two daughters in an Italianate mansion outside Las Vegas. He collects jackets and cars and boots. His current favorite Swiss watch is an Hublot, which his wife had a local bakery re-create recently as a birthday cake at an expense of $1,000. When asked, he says he's a photographer.

Tawny and taut, with twinkly eyes and TV teeth, Tom looks even more like Rob Lowe than Rob Lowe looks like himself. He has the appearance (faultless) and bearing (dauntless) of a very lucky person, which he is, and which he is usually capable of remembering. Tom has a loving family, a beautiful home, a creative career, and lots of money. He also has a mortal enemy. When Tom talks about Stefano Zandri—or, as he calls him, “Stefano or Den or Whatever”—the grace with which his life has been blessed disappears, instantly it seems, from the foreground of his mind. He begins to swear and to brag; he becomes bothered by minor three-decade-old slights. Tom mocks Stefano for not speaking English, for “not having a pot to piss in.” He calls him “obnoxious,” a “chronic liar,” “a horndog with low standards and no selection process.” To observe this transformation, from blessed family man to apoplexy incarnate, is to bear witness to something almost mythic. Like if Achilles' problem wasn't his heel but his toe, which he stubbed, repeatedly, over the years and which every time he did sent him into a temporary infantile rage.

To be fair, Stefano himself isn't above Tom-directed barbs, which he spouts in Facebook posts, Instagram comments, and national radio interviews, and which he tends to express with an impressive, almost poetic specificity. “Needle dick” is one of his preferred insults. For years he's been preoccupied with the notion that Tom bought the exact same Porsche as he did in 1989. On Facebook, he's called Tom “envious and troubled,” a “clown,” a “brown-noser with no personality,” a “small penis man,” a “Coward!” “You should be ashamed that you sold your voice,” he's written. “You are clumsy and you have a bad energy as you are a bad person.” A few weeks after writing “I would put your head in your butt for real,” Stefano threatened Tom, saying, “I know where you live. I will come to Vegas and kick your flaccid ass.” Tom's two daughters were 5 and 6 at the time, and the threat to his family infuriated him. Tom insisted to me that he wasn't actually scared but then added, “I don't know—maybe he has some guys around!”

Tom would like to forgive Stefano—for the lying and the insults and the threats of violence. Maybe there was a time that would have been possible, but it seems unlikely. And maybe, if Stefano had actually seen the film, Dons of Disco, he would have felt more secure in his own legacy, knowing that a young American, a guy with no firsthand memory of Den Harrow and no motivations apart from his own curiosity, found him to be smart and sympathetic and worthy of respect. He would have realized that he wasn't portrayed as a villain but as a surprisingly articulate victim with sophisticated ideas about himself and Tom and what they had made, all those years ago, together.

1911651

Just a few weeks before Los Angeles went up in flames this past fall, Jonny was pacing around the Norwegian Air lounge at LAX. He'd finished editing the film earlier in the month, and now it was time to start actually showing it to people. But already he was worried that his newly minted career as a documentary director might be in the early stages of combustion. In just a few minutes, he would board a 12-hour flight to Italy, where Dons of Disco was to premiere at the Rome Film Festival. A couple of hours earlier, but already the following day in Spain, a 56-year-old Milanese man living in Malaga posted 15 pathos-ridden paragraphs on Jonny's Facebook page. He spoke of “mercenar[ies],” “senseless polemic,” and “pathological obsess[ion],” a “magical and unrepeatable” past and the “mystifications of those consumed by unreasonable envy.” The whole thing had a late-Mario Puzo feel. In the penultimate paragraph, he wrote, “I will sue Jonathan Sutah [sic] for fraud and copyright infringement.” It was signed, 17 lines later, “Stefano Zandri, aka Den Harrow.”

“Goddammit,” Jonny muttered.

He called his lawyers and his translator. Together they drafted a response, which they would send to the organizers of the Rome Film Festival as a kind of pre-emptive defense against any attempts by Stefano to censor the film. Jonny had all the releases signed; he had Stefano—on-camera!—agreeing to everything in no uncertain terms. But then again, why would a film festival ever expose itself to even a modicum of legal risk, all to protect the creative vision of an unknown first-time director from halfway around the world? Better safe than sorry.

When Jonny landed in Rome, it was the following day but the exact same temperature it had been in Los Angeles. The organizers hadn't responded to his e-mail. There was nothing he could do but wait and hope that Stefano didn't pull any career-damaging shenanigans. He checked into his hotel, tried and failed to nap, ate some pasta, spent a crappy night not sleeping.

Tom signed some records, pleased with the belated acknowledgment, and shook his head. “To be a fan of a mime,” he said, “you have to be a pretty weird kind of guy.”

The next day, Jonny met up with Tom and his wife, who had arrived straight from Las Vegas, for an alfresco lunch by the Spanish Steps. The conversation was sprightly and skippered mostly by Tom, with brief, unbidden diversions for self-defense demonstrations. Waiters deposited plates of arancini on the table with great ceremony; bambini wailed nearby. Tom, just back from an antagonistic radio interview conducted by one of Stefano's friends, offered up his opinions on the appearance of Madonna (“Hot but not hot enough”) and the Pet Shop Boys (“not particularly good-looking”). He wondered aloud whether or not one day Sony might re-release the Den Harrow master recordings, which are currently available only on YouTube, and attach his own name to them. He'd pay for the privilege. “A hundred grand? I'd write the check right now.” He loved the idea. “It would really piss Stefano off,” he said, before taking a sip of wine.

Before excusing himself to go buy a jacket at a luxury boutique, Tom gave a little anthropology lesson, in hopes that it might explain the Den Harrow situation. “Let me tell you something about Italy,” he began. “In the '80s, they would smash your window in to steal your car radio. Always. So you'd take it out of the car and bring the stupid thing into the bar or wherever you were going, because otherwise they'd take it. A real pain in the ass.” He continued on to explain that, on occasion, to save himself the hassle, he'd hide the contraption under the seat rather than dragging it around with him. “But sometimes,” Tom said darkly, “it didn't work. And if you ever told anyone—a bartender, say—that your car radio was stolen, the first thing they'd ask you was, ‘Well, did you leave it under your seat?’ And if you said yes, their response was, ‘It's your fault, then, stupid!’ ”

Tom took another sip of wine and waited a moment for everyone to absorb what he was trying to convey. “That's how Italians are,” he said. In a country so ridden with cons, where the rules are bent constantly and everyone lies, guile is a national requisite, naivete inexcusable. “They would be embarrassed to admit that they didn't know Den Harrow was a fraud.”

A few hours later, as the sun began to set on the elaborate English-style grounds of the Villa Borghese gardens, Jonny arrived at a theater on the park's periphery. Tom showed up a few minutes later with his wife; his niece was there, too. A handful of aging Italo Disco fans milled around the crushed-granite garden paths, along with some film critics and aspiring young directors. There was a journalist from La Repubblica, Italy's largest daily paper. Stefano was nowhere to be seen, but Jonny couldn't stop himself from compulsively looking for him. It seemed like at any second Stefano might pop out from behind a well-tended topiary, Prada messenger bag worn like a shield, screaming, “Bastardo!”

At some point, as the dusk turned to dark, a festival employee ushered everyone into the theater. The curtains went up, revealing a black screen with an epigraph: Art has a double face, of expression and illusion.—Publilius Syrus. The 85-minute film that follows is about as good as feature documentaries get. It's like watching a perfectly crafted fairy tale in which medieval princesses have been replaced with aging men fighting on Facebook about the legacy of their intertwined Bettino Craxi-era lives. It's beautifully shot and scored, with clever visual gags, psychological precision, and shifting, unstable sympathies. It's atmospheric and ambitious, astute to the obligations that attend success, the inherent tragedy of fandom, and the psychic cost of self-awareness. It's sad and philosophical but also really, really, really funny.

When the credits closed, the festival organizer invited Jonny up to the stage. Tom joined him and, almost immediately, began a protracted, staccato monologue—in Italian, mostly, which ended, somewhat mortifyingly, with another a cappella performance. Jonny just stood there. He'd assumed the worst before showing the subject of his film the final product for the first time, and was relieved when, 25 minutes later, Tom grinned and congratulated him.

Afterward everyone migrated to a bar-adjacent patio. Tom, red wine in hand, looked serene, which was probably because he had spent the past 24 hours, like Jonny, half expecting to see Stefano for the first time in 30 years and then realizing, finally, that it wasn't going to happen. He joked around; he kissed his wife. He signed some records, pleased with the belated acknowledgment, and shook his head. “To be a fan of a mime,” he said, “you have to be a pretty weird kind of guy.”

A month later, Stefano published a memoir, under the name Den Harrow. He's been diligently posting about it on Facebook ever since. After premiering in Rome, Dons of Disco was shown at film festivals in Arkansas and Portland and is now playing in Park City. Perhaps, for the sake of publicizing his book, Stefano will come around. Maybe he'll decide it's time to actually watch the film. When he does, he'll see that he is, in a very real way, its hero. This is what I wanted to talk to Stefano about when I reached out to him this fall. He was responsive at first, replying, always, with kissy-face emojis, but in the end he refused to talk, convinced, as he was about Jonny, that I was on Tom's side. If the film goes on to great acclaim and success, as it should, there will be many more festivals, many more screenings, many more opportunities for the face and the voice to show up, look each other in the eye, and potentially make amends. But who knows if they'll do it.

1911654

With its dated stage costumes and obsolete electronic effects, Italo Disco lives on as a kind of globalist kitsch—recalled fondly, if with a bit of chagrin, by those who were there, and mocked, affectionately, by those who weren't. It's unsurprising that two of the genre's key players would fight over its mostly forgotten legacy. Like adjunct English professors committed to undermining each other's precarious and underpaid careers, Tom and Stefano are animated by an insular, low-stakes game that must feel, as all lives do to the ones who live them, like everything. But their petty warring has driven them both from a scene they once ruled. By fighting for their respective shares, they've managed to poison for themselves something they could have instead chosen to see for what it was: a ridiculous, beautiful thing that brought joy to millions of people.

I was thinking about all this when, a few months ago, I got a cryptic e-mail invitation to an Italo Disco-themed dance party. It was to be held on a Friday night in early December at a Ukrainian social club in New York's East Village. The venue was wood-paneled and dusky; the guests had more glitter on their faces than I'm used to seeing.

By midnight, I was impatient to hear Den Harrow and sent someone to make a request on my behalf. He returned, a few minutes later, with the bad news. “Den Harrow's not on Spotify,” he said. “Sorry.” I couldn't believe it. Crestfallen, I made a move to the bar for a glass of water. I wasn't halfway there when a boa-wearing friend, hearing the initial high-pitched choral warbling of an Abba song, grabbed my hand and dragged me barbarously back to the dance floor. I forgot about Den Harrow.

This all came back to me, a little blinkered, the next morning. I guess afternoon is probably more accurate. Nursing a Gatorade in bed, I searched for Den Harrow on Spotify, something I hadn't ever thought to do. Den Harrow was on there! The DJ had been wrong! Sort of. I realized when I pressed “play” that all the songs had been re-recorded, in 2016, with Stefano singing.

Alice Gregory is a GQ correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2019 issue with the title "Dance Battle!: Meet The Warring Milli Vanilli Of Italo Disco."