Damilola: the Boy Next Door, review: an honest and uplifting portrait of the real Damilola Taylor

‘I’ve always been in denial,” said Yinka Bokinni. “Put it away and deal with it later. But later is now, I guess.” Damilola: The Boy Next Door (Channel 4) was a captivating and quietly devastating documentary which found Bokinni revisiting the day her innocence died.

She’s now a successful radio DJ. Yet 20 years ago, Bokinni was a schoolgirl living on southeast London’s North Peckham estate when her friend and neighbour Damilola Taylor, aged 10 just like her, was stabbed and left to bleed out in a stairwell.

This shocking murder became a defining moment for a generation. Within months, the troubled estate was bulldozed. Bokinni and her friends were rehoused, dispersed to different locations and unable to grieve together. She grew up never mentioning Damilola, nor even admitting she was from Peckham. It turned out that she was by no means alone. They all held onto this painful secret, building a protective shell around themselves.

For this raw and powerful film, the fiercely honest Bokinni set out to process her experiences by returning to Peckham, meeting fellow residents from the time and attempting to reconcile her memories of an otherwise idyllic childhood with an area which was demonised as a crime-ridden no-go zone.

For the first time, she confronted the ripple effects that Damilola’s death had on everyone she knew. What emerged was part tribute to Damilola, part personal memoir and part paean to a lost community which yielded many success stories alongside the tragedies. This wasn’t a gang-ruled sink estate but a vibrant, tight-knit neighbourhood, full of laughter and love. As Bokinni’s sister, Shade, said: “It was a s---hole. But it was our s---hole.”

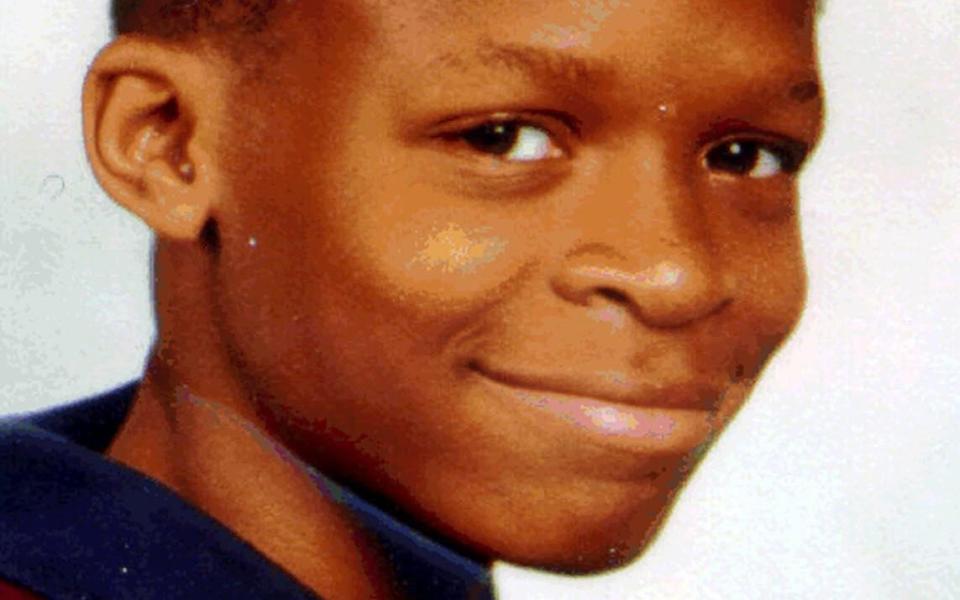

Bokinni met Damilola’s father, Richard Taylor, who has dedicated the last two decades to tackling youth violence. He thanked her for “looking after my boy” and gave the film his blessing. Rightly so, because this was a warm portrait of the freckly, boisterous lad everyone called “Dami”. Bokinni painted him as a rounded human being, rather than the symbol he became. A bundle of fun and contradictions, not just a victim.

This was a subtle, moving look at class and community, loss and trauma. There were no heartstring-tugging histrionics, just hard-won wisdom, righteous anger and bittersweet reflections.

For a film about the loss of a young life, it was somehow uplifting and redemptive. No mean feat.