Dame Vivienne Westwood, Punk Pioneer, Dies at 81

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

LONDON — Dame Vivienne Westwood, who was responsible for ushering in the punk fashion phenomenon of the ’70s and whose subsequent designs from pirates to crinolines also had major influence through later decades, died Thursday at the age of 81.

During Westwood’s multi-decade career she defined British fashion with her eccentric designs, style and environmental activism.

More from WWD

The brand revealed the passing away of Westwood on Instagram, stating she died peacefully surrounded by her family, in Clapham, South London.

“Vivienne continued to do the things she loved, up until the last moment, designing, working on her art, writing her book, and changing the world for the better. She led an amazing life. Her innovation and impact over the last 60 years has been immense and will continue into the future,” continued the post.

“Vivienne considered herself a Taoist. She wrote, ‘Tao spiritual system. There was never more need for the Tao today. Tao gives you a feeling that you belong to the cosmos and gives purpose to your life; it gives you such a sense of identity and strength to know you’re living the life you can live and therefore ought to be living: make full use of your character and full use of your life on earth.’”

“I will continue with Vivienne in my heart. We have been working until the end and she has given me plenty of things to get on with. Thank you darling,” said Westwood’s husband and creative partner, Andreas Kronthaler.

Westwood was born in 1941 in Tintwistle, in the East Midlands of England. By 1958, her family moved to Harrow in the London Borough of Harrow and this is when she showed an interest in fashion by enrolling in a jewelry and silversmith course at Harrow Art School, now known as University of Westminster, but dropped out after one term.

She had a short stint as a primary school teacher while simultaneously creating her own jewelry and selling it at a stall on Portobello Road.

Westwood met her first husband Derek Westwood in 1962 and married him that same year in a wedding dress that she made herself at the age of 21.

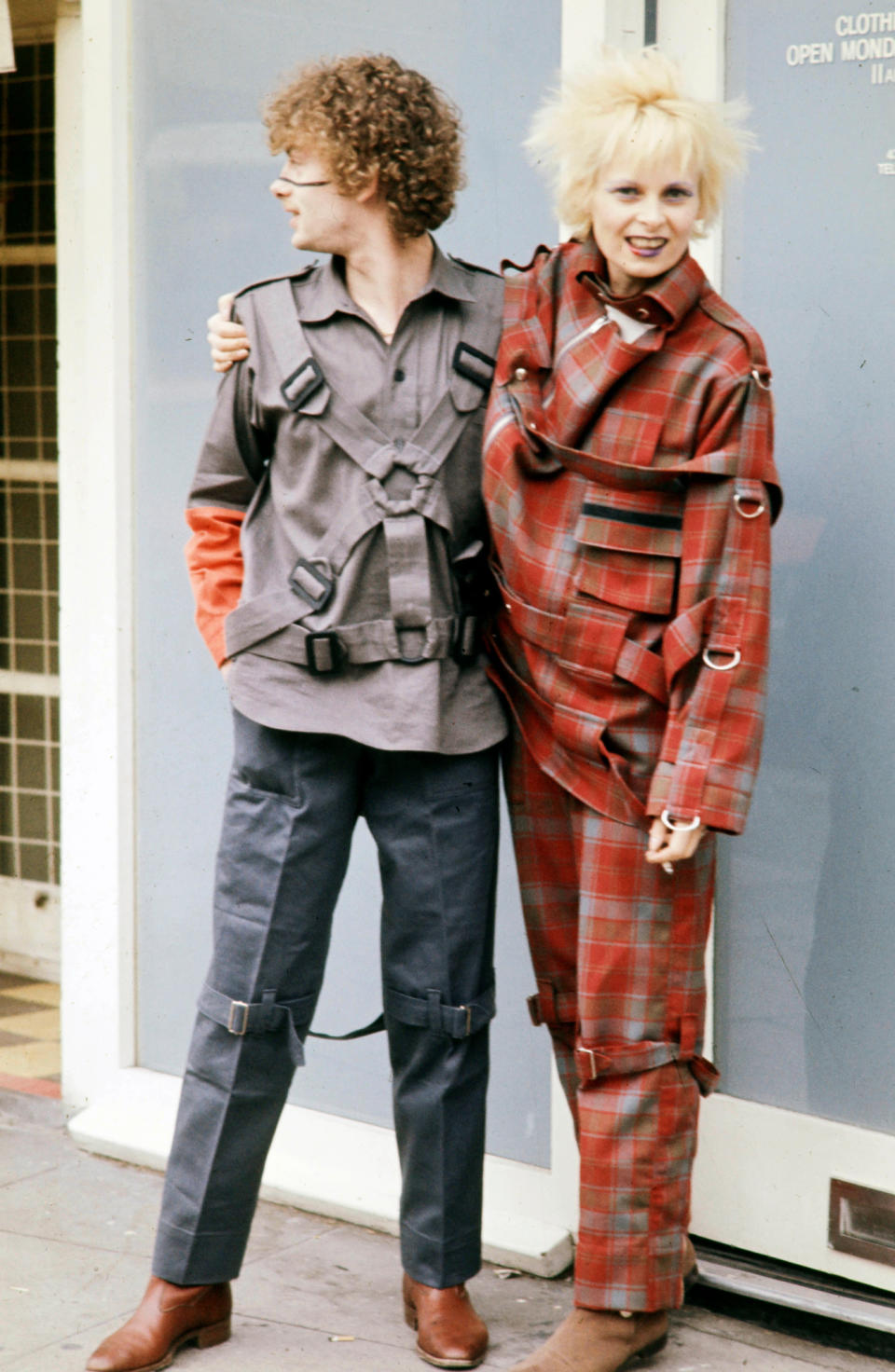

The couple divorced when she met Malcolm McLaren in 1965, the manager of the Sex Pistols and the driving force behind punk along with Westwood.

They opened a boutique on 430 Kings Road in London’s Chelsea in 1971, where Westwood sold her designs that were worn by the Sex Pistols and the New York Dolls. She once recalled to WWD how she would be in the back of the shop sewing the clothes on a sewing machine and they would then be put on rails out front and sold to customers.

The store would change its name every time Westwood designed a collection, from “Let It Rock” and “Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die” to “Sex,” “Seditionaries” and “World’s End.”

On stage, members of the Sex Pistols such as Johnny Rotten would rip his shirt and Sid Vicious would use safety pins in his clothes — and an aesthetic that became synonymous with Westwood was born.

“I began fashion as a rebel expressing myself through clothes. We chose the ’50s for our inspiration because that seemed a time when youth rebelled against age: See you later, daddy, you’re too square! The hippies politicised my generation and I hated a world of torture and death organized by the western world,” wrote Westwood in her 2016 book “Get a Life: The Diaries of Vivienne Westwood.”

In 1981, Westwood debuted her first fashion show on the London catwalks, titled “Pirates.” The inspiration indicated her lifelong fascination with history and art — topics that she often referenced in both her designs and her conversations. She never seemingly lost the air of the school teacher she once was, in her soft voice taking any interview along multiple paths that could wind seamlessly between the Renaissance, World War II, the environment and modern-day politics.

“I have this horrible streak of pedagogy in me, and I get bored with myself,” she once told WWD. She was often quoted as saying that the best fashion accessory was a good book. “A good book,” she told WWD with a smile, “and high-heeled shoes. I like them as well.”

“The idea for Pirates was culture. Let’s get off this island and explore history and the third world/Exchange black for gold. Subversion lies in ideas,” Westwood wrote, name-checking her friend Gary Ness for opening up her world by introducing her to new music, ballet, authors such as Aldous Huxley and Bertrand Russell, 17th-century Dutch paintings and Chinese art.

Westwood’s relationship with the abusive and often absent McLaren eventually came to an end in 1983.

“It was an immensely creative relationship that turned unpleasant,” British stage and screen actor, playwright and historian Ian Kelly told WWD in 2014 ahead of Westwood’s biography he worked on.

He added that Westwood was forced to confront her difficult past. “Having been described by Malcolm as ‘just a seamstress,’ she’s said, ‘Well no, actually, I made this, I did this, and I’m immensely proud of being a part of her saying that stuff,’” said Kelly.

The duo split and battled over the future of what was then called World’s End. McLaren wanted the production and brand to remain in England, while Westwood wanted it to relocate to Italy and be sold to Fiorucci.

In the end — in what turned out to be a marriage of opposites — Westwood signed a seven-year licensing agreement with Giorgio Armani in 1984 that gave the Italian designer exclusive rights to her name. But no clothes were ever produced under the agreement and in 1987 Westwood actually sued Armani for failing to pay her.

Despite the late McLaren’s horrid behavior toward her and their son, Joe Corré, Westwood remained extraordinarily generous about the man’s talent, wit and influence on her work and way of looking at the world.

“Through Malcolm, I was able to look at society and politics and culture,” she said in the book, “and he influenced the way I dressed and thought about clothes, too. He cared passionately for clothes and he transformed me from a dolly bird into a chic, confident dresser. It wasn’t for love of me. He loved clothes.

“Punk was everything to me and Malcolm….What I am doing now, it still is punk — it’s still about shouting about injustice and making people think, even if it’s uncomfortable. I’ll always be a punk in that sense,” she added.

For someone with Westwood’s outward energetic attitude toward design, her practice was rooted in tradition and borrowing from the past. She used Harris Tweed fabrics for tailoring; silk and taffeta for her 18th-century inspired silhouettes; voluminous shearling; mohair; cashmere, and Grecian drapery.

“Where would I get ideas if they didn’t come from the past? The great age of clothes was the couture until the 1950s. We have no hope unless we refer to the past,” Westwood told WWD in 1994.

As the ‘80s rolled in wide shoulders, plenty of pouf and bold-colored gowns, Westwood didn’t hesitate to try and catch up with the pace of the time. Instead, she moved on from punk rock and looked to ridicule, comment and repurpose the look of the upper class and Tatler girls.

For her spring 1985 Mini Crini collection, she looked to the ballet “Petrushka.” The collection combined 18th-century gowns with tutu dresses in rich red wine velvets and delicate white lace on Marilyn Monroe-esqued models. It would have a major fashion impact and be aped on runways from Tokyo to New York, Paris to Milan. WWD dubbed the Paris version “Le Pouf,” while Westwood simply called hers crinolines.

“My prestige has never been as high as it is at the moment because I have such a lot of innovations under my belt,” she told WWD in a 1986 interview. “It has always been the case that when others copied me, they lifted me up with them.”

Westwood introduced her orb logo as a symbol of taking tradition into the future, as well as referencing her fascination with royalty.

“British Vivienne Westwood is the designer’s designer, watched by intellectual and far-out designers, including Jean-Paul Gaultier. She is copied by the avant-garde French and Italian designers, because she is the Alice in Wonderland of fashion, and her clothes are wonderfully mad — fantastic enough to be worn at the Mad Hatter’s tea party,” wrote John Fairchild in his 1989 memoir “Chic Savages,” comparing her personal style to Queen Elizabeth II in Harris Tweed with high-laced pilgrim shoes.

Fairchild considered Westwood one of the world’s six greatest designers, along with the likes of Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio Armani, Karl Lagerfeld, Emanuel Ungaro and Christian Lacroix.

Westwood’s next five collections focused on British-ism, to which she called her “Pagan years,” and the collections would go on to be called “Britain Must Go Pagan.”

Her fall 1987 collection was inspired by a little girl she saw on a train wearing a Harris Tweed jacket.

“Tailoring is the basis of my collection, which is as it should be, because it’s the basis of English fashion,” Westwood said in WWD in 1994.

“But until recently, I was changing my tailor every season. In Britain, they have this laissez-faire attitude toward small business, that they will just spring up on their own without any help from the government. Now my tailoring is quite good, because I have a little atelier here and another one there, and so forth. But I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Italy. They may have corrupt politicians, but at least they do something for the businesses.”

Westwood steered in a new aesthetic in the ‘90s as she married Austrian design student Kronthaler, who became her partner in life and work over the span of more than two decades.

The couple’s partnership led to success. Westwood received the Fashion Designer of the Year award in 1990 and 1991 from the British Fashion Council.

Soon Westwood’s efforts in fashion were awarded with an OBE from Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace in 1992.

The designer accepted the award in a gray suit-skirt — while posing for the cameras after the ceremony, she twirled in her skirt and unintentionally exposed her bare crotch.

“It did not occur to me that, as the photographers were practically on their knees, the result would be more glamorous than I expected,” she later explained, adding that she had heard the queen had found it amusing.

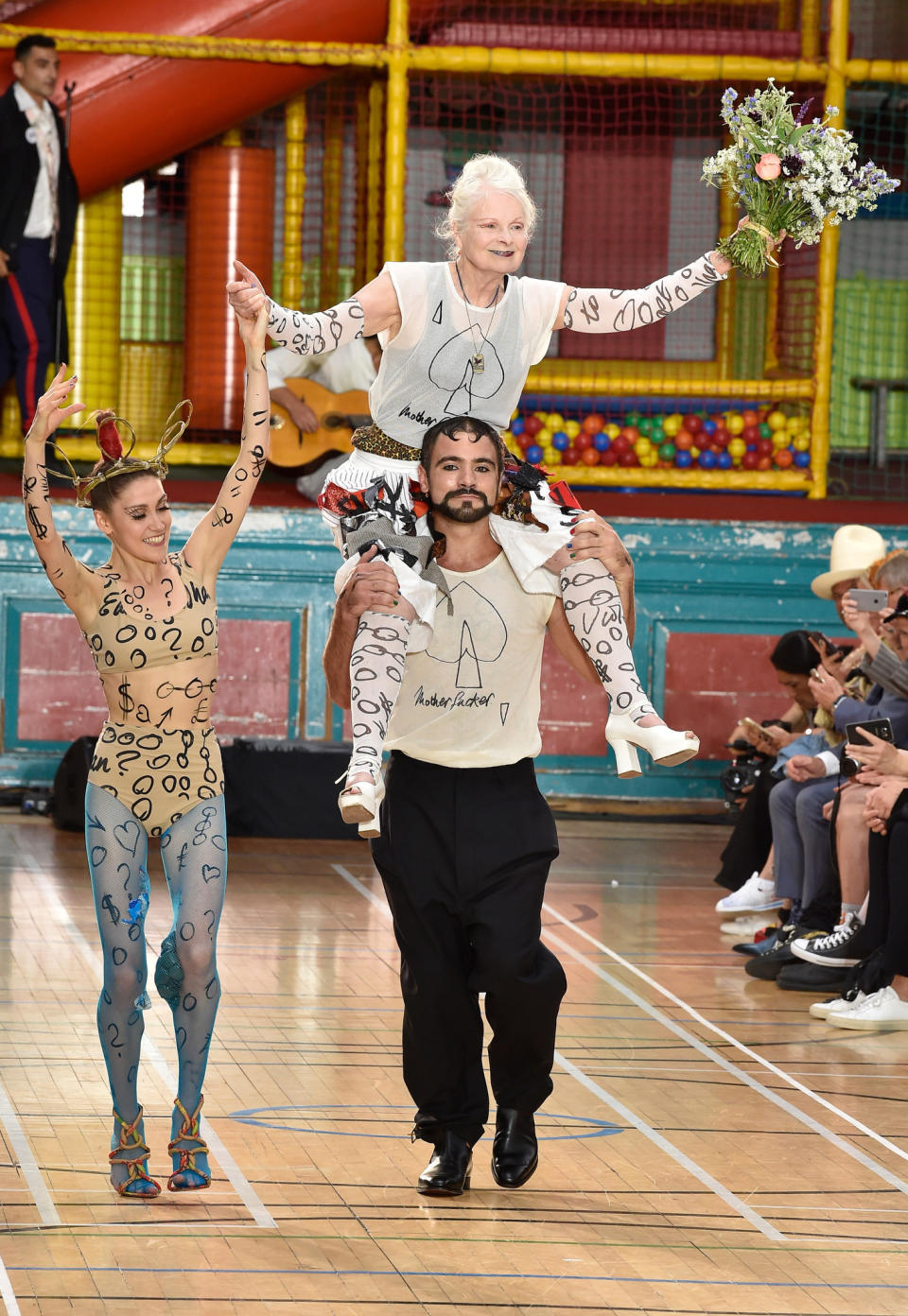

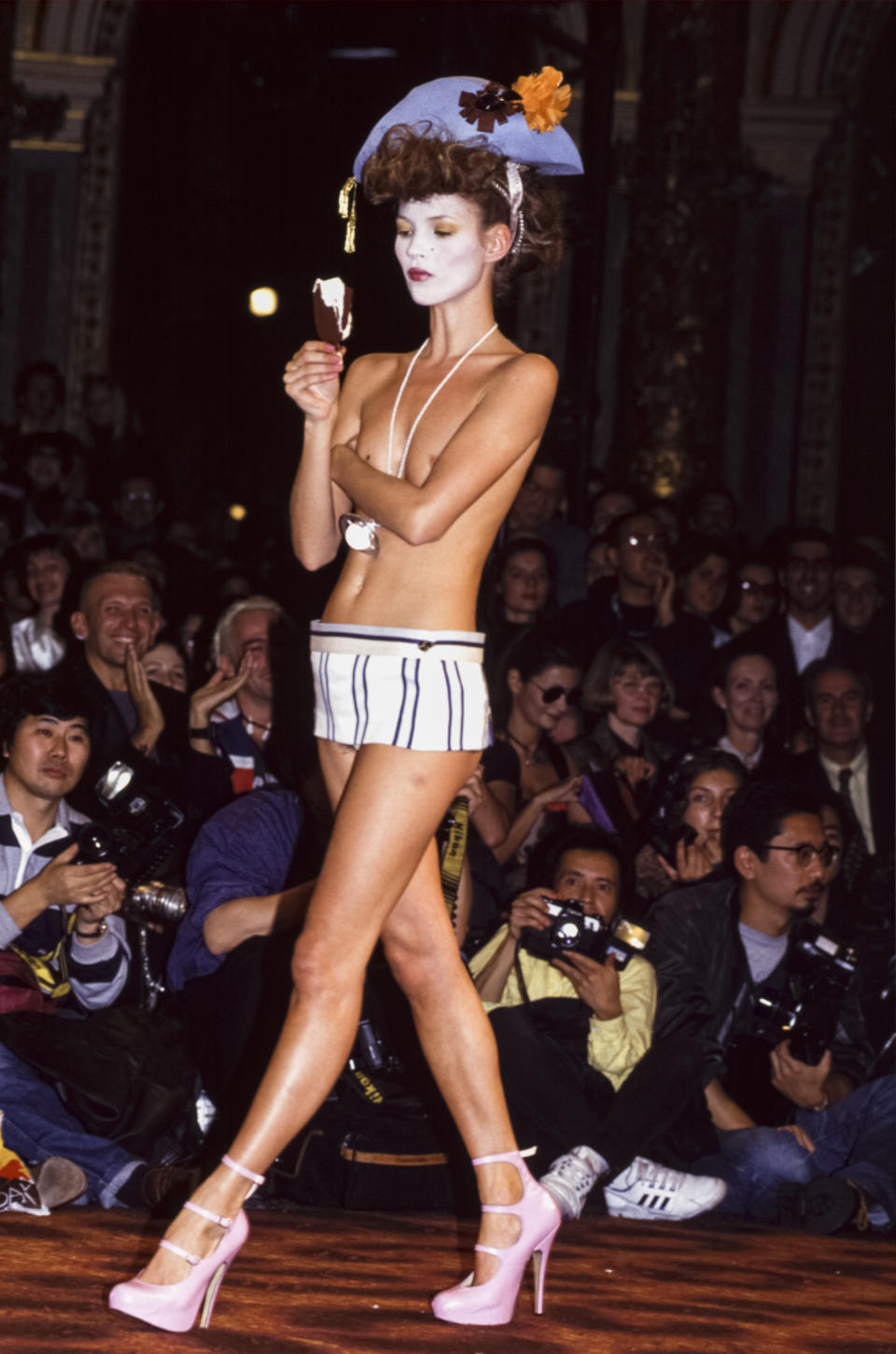

Forever the mischievous designer with a wicked sense of humor, the ‘90s showcased her subversive silliness with a cue of supermodels: Naomi Campbell at 16, tumbling down the runway in 9-inch platforms during the fall 1993 show; Carla Bruni strutting down the runway with her hands on her hips in a faux fur coat and matching underwear; Kate Moss swanning in Marie Antoinette face paint, topless down the Erotic Zones runway show of spring 1995, eating a chocolate ice cream.

A lover of tartan, Westwood created her own for the “Anglomania” collection and imagined her own clan, the MacAndreas, which was officially recognized by the Lochcarron of Scotland.

But even as influential as her designs often were, Westwood never reached the mega success of her European or American peers. While major U.S. retailers did carry her collections, a lot of her sales through the late ’80s and ’90s were in Japan. She did open a flagship in London’s Conduit Street in the ’90s, and ventured into fragrances by launching Boudoir in 1998 with Martin Gras of Dragoco, who helped create such scents as Cerruti 1881 pour Homme, Lapidus Pour Homme and Bleu Marine for Pierre Cardin.

“My perfume is called Boudoir. A boudoir is a dressing room and a place to get undressed. It signifies a woman’s space, a place where she is on intimate terms with herself, where she sees her faults and her potential,” Westwood explained behind the idea of the scent.

Westwood’s Red Label launched in 1999 — a ready-to-wear line that combined Savile Row tailoring with French couture. That same year, she opened her first New York boutique.

FIT’s Valerie Steele said via email Thursday that Westwood had a huge impact on the world of fashion. “She was not only the high priestess of punk, she also pioneered the radical combination of historic references and contemporary subcultures, often doing research in the dress collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Galliano and McQueen were definitely influenced by her, but so was Christian Lacroix.”

Tommy Hilfiger said, “Vivienne and Malcolm McLaren were behind the punk rock scene in London in the ’70s with the Sex Pistols. It was a powerful fashion music revolution at the time. I visited their store on Kings Road in the early ’70s. It was an exciting and memorable experience I’ll never forget. This inspired me to open a punk rock shop in 1974 called The Underground in the basement of my store, People’s Place. Vivienne was a visionary, a force and a committed activist. Her legacy as a trailblazer is indisputable.”

Andrew Burnstine, associate professor at Lynn University’s College of Business and Management, who is the grandson of Martha’s founder and chairwoman Martha Phillips, said, “Martha discovered Vivienne through the buying office we had in London at the time. Her first show was a tremendous hit. I always remember the incredible Elizabethan gowns coming down the runway, with models draped in pearl necklaces, flowing trains of lace infused with flowers and elegant trimming. There were mirrors on the walls and sconce lighting illuminated the entire area. I thought I was a part of a royal wedding, or ceremony, awaiting the final entrance of Elizabeth I.

“Martha, Lynn [Manulis, Phillips’ daughter] and I went to the showroom a day or two after the show. Vivienne was there and greeted us with her resounding English voice. She proceeded to assist her sales team explaining the collection, and also gave us an incredible fashion history as well, discussing the importance of fashion and the Elizabethan era. I will never forget her meticulous eye, her dedication to detail, and what I learned about the history of fashion from who has become for over five decades the ‘voice’ of fashion for this century. Vivienne did do a trunk show with us in New York during her second year in business. It was a huge success. Customers were lining up to try on some of the gowns that were a part of the trunk show collection. Martha’s took a lot of orders, and when the clothes were delivered months later, they fit to perfection.

“And now, as a professor of fashion, when I talk about Vivienne Westwood with my students, I mention the fact that there is perhaps no other designer of our lifetime who has created fashion from so many different eras and times. From Elizabethan to the Priestess of Punk, her ‘circular’ fashion looks have linked the past, present and the future. As Vivienne so aptly stated, ‘Fashion is life-enhancing, and I think it is a lovely generous thing to do for other people.’ And by all accounts, she has definitely achieved her goal.”

Julie Gilhart, chief development officer, Tomorrow Ltd. and president, Tomorrow Projects, who was previously senior vice president, fashion director at Barneys New York, said, “She was the queen. She influenced so many up-and-coming designers and will continue to. She took risks that others would never do and was an early activist for the planet and forever continued to wave the green flag. She never lost her youthful approach and passion. Her legacy is vast and will continue to inspire future generations.”

Describing Westwood as “a true original and game changer in so many ways,” Michael Kors recalled Thursday meeting her in Scotland at a fashion event in the early ’90s. “I was taken with her wit, intelligence and sharp humor,” Kors said.

He continued, “Her influences ran the gamut from the street and music to historical references, and she always delivered in her own inimitable style. From punk to corsets to platforms, her vision changed the way women dressed and saw themselves. Her influence will continue to inspire generations to come.”

By the early 2000s, Westwood had established herself at the forefront of British fashion and was internationally recognized. But her messaging had turned to the environment and politics along with her son, Corré, cofounder of Agent Provocateur.

In 2016, Westwood joined her son at a ritual burning of punk memorabilia in defiance of celebrations to mark the 40th anniversary of the movement.

The rally — which was livestreamed — took place near the Albert Bridge in Chelsea, and saw a crowd of 200 supporters and press gathered on the riverbank to watch Corré set fire to his belongings from an ex-Navy minesweeper ship on the Thames.

The boat was decorated with a sign “Extinction! Your Future” along with a couple of Grim Reaper-like skeleton figures and a climate change map. Corré set fire to clothes, records, posters and other items that had been laid inside a chest, along with figures of politicians such as former Prime Minister Teresa May and David Cameron. Onlookers watched as the items were burned, and a small display of fireworks went off.

“Punk was never, never meant to be nostalgic,” Corré said. “Punk has become another marketing tool to sell you something you don’t need. The illusion of an alternative choice. Conformity in another uniform.”

Westwood marked her 80th birthday in 2021 with a string of social and environmental warnings and a short film in which she sings a rewritten version of “Without You” from the musical “My Fair Lady.”

She worked on a film with Circa, which commissions a different artist each month to create a new work for Europe’s largest screen in London’s Piccadilly Circus.

In a written message that appears in the film, Westwood said: “I have a plan 2 save the World. Capitalism is a war economy + war is the biggest polluter, therefore Stop War + change economy 2 fair distribution of wealth at the same time.”

She called on people to “stop arms production + that would halt climate change cc + financial Crash. Long term this will stop war…by talking U will support me in the fight. One day soon U will say the right thing 2 the right person at the right time, make a difference. I have always combined fashion with activism: the one helps the other. Maybe fashion can Stop War.”

— With contributions from Lisa Lockwood and Rosemary Feitelberg

Launch Gallery: Vivienne Westwood Dies at 81: Images Through the Years

Best of WWD