Dallastown dad turns trauma into advocacy after his 15-year-old daughter Brianna's suicide

It was the afternoon of Dec. 3, 2020, and Matt Dorgan found himself lying in his driveway in his jeans and T-shirt, no shoes, no socks.

That Thursday afternoon was chilly, but he didn’t feel the cold. He felt nothing. He remembers lying there. He remembers the police arriving. He remembers talking to the police officers who arrived at the house and watching one walk inside only to emerge a few moments later. He remembers asking him, “Is she gone?” He remembers the officer answering with a slight nod of his head.

He remembers later, driving away from the house with his son, John.

He remembers everything.

He had no idea what he was thinking. One moment, everything seemed OK, and the next, everything was different.

There may have been clues. She had struggled in the past, a result of being abused when she was younger. But that day she seemed to be doing OK. Later, Matt remembered some signs, nothing that in the moment raised any concerns. He remembers her telling him that she wasn’t going to be there forever. He thought she was talking the day she graduated from high school and moved out, leaving him with an empty nest.

“Not that she’d be gone,” Matt said later.

Finding meaning in grief

That Thursday afternoon, Matt’s 15-year-old daughter, Brianna, a sensitive young woman who loved poetry, animals and art and feared clowns, heights and needles, took her own life.

She had struggled with mental health issues for several years, having been hospitalized four times, the last coming just weeks before she ended her life.

Matt struggled along with her, and after her life ended, he searched for something to do to prevent others from going through what he has endured for the past four years, something to find meaning in his grief.

It came to him 24 days after his daughter’s death.

The consequences of mental health issues

Brianna was born in Key West on March 8, 2005, the second of Matt and April Dorgan’s three children. She came into the world early. “She couldn’t wait to come out,” Matt said. “I pretty much delivered her in the waiting room.”

She was a “true conch,” Matt said, a Key West native. He was a transplant, having moved to Key West to pursue a career in marine engineering upon graduating from high school in York. He worked several odd jobs, including taking tourists on jet ski tours, and was working at a club when he became acquainted with several local police officers. They talked him into enrolling in the academy – Key West’s police academy is on the beach – and he soon found himself on the island police force. He liked it; it had always been a dream, he said, to get into law enforcement.

During his second week of field training, accompanied by a senior officer, he encountered the consequences of untreated mental health issues.

He and his training officer were dispatched to a suicide. The victim was in the ER, and he and his partner went there to collect evidence. He walked into the curtained-off room, a self-described “big, tough cop” just 22 years old – and saw the victim on a gurney, his chest splayed open by the doctors who struggled to save his life. He froze. “I almost fell over,” Matt said. “Here I was, a cop, and I couldn’t deal with it.”

That always stayed with him, something that inhabited the dark recesses of his mind. A few years later, he said, he learned of the suicide of one of the cops he served with on the night shift in Key West, a K-9 officer who would come by Matt’s traffic stops to have the dog conduct drug sniffs. The cop always seemed upbeat.

“I didn’t know he was struggling until he took out his service weapon and took his own life,” Matt recalled.

'I knew something was going on'

Matt and Brianna’s mother split when she was about 6. Matt moved back to Pennsylvania and Brianna moved to Dansville, near Buffalo, New York, with her mother and brothers, Zachary and John.

When she was about 11 or 12, Matt recalled, she called him while he was at a conference. By now, Matt was working in loss prevention for a retail chain and was busy with conference work when she called five or six times. It was unusual, Matt said; Brianna didn’t call him while he was working. He called her back when he got out of the conference and she asked, “Hey, Dad, can I move back in with you?”

At the time, Brianna was living with her mother in North Carolina and was going to be traveling to a wedding in New York, bringing her in the neighborhood of Dallastown, where Matt was living. A week and a half later, she moved in.

Matt wasn’t sure why she would want to move in with him. “She didn’t say why, but I knew something was going on. Something happened.”

Later, Matt would learn.

Brianna seemed fine, Matt said. She was outgoing and friendly. Once, while vacationing in Myrtle Beach, she befriended another girl, and they spent the entire vacation together. They stayed in touch for years, Matt recalled. She had a lot of friends and they often hung out at Matt’s house with her, he recalled.

She always cared about other people, Matt said. While grocery shopping, Matt turned up an aisle, looking at the groceries when he noticed that Brianna, who about 11 or 12 at the time, was not by his side. He panicked, thinking what kind of father loses track of his daughter in the grocery store. He went to look for her and found her in the next aisle, assisting an elderly couple with their shopping, pushing their cart and picking items off the shelves for them. She accompanied them through the checkout and to the parking lot, where she loaded their groceries in their car.

A story of hope: She was hit by a drunk driver on I-83, got out to help, was hit by a car & lost both legs

Turning trauma into art: York Vietnam vet's haunting, powerful sculpture reflects the horrors he experienced in war

She loved bacon and pizza, Matt said. He recalled once he had cooked up a bunch of bacon for breakfast that disappeared quickly. It turned up in her purse; she was saving it for a snack later. Another time, Matt was working in another room when Brianna called to him from the kitchen, “Dad, I need help.” Matt said he’d be there in a minute, but she insisted he come right away. She had been heating up supreme pizza, and it wound up upside down, the toppings falling to the bottom of the hot oven. “How the pizza got upside down, I have no idea,” Matt said.

She also loved animals and dreamt of, one day, having a zoo. She competed, successfully, for the affections of Matt’s German shepherd, Milo. She wanted to get cats, but Matt told her it wasn’t a good idea, that Milo didn’t cotton to cats and if they came in the house they may not last long. She also wanted to get a pig and a monkey, he said. “I said no,” Matt said. “We’d need a bigger house."

A cry for help

One day, Matt was leaving the house to go to a friend’s when he noticed an extension cord and a ladder on the floor. He didn’t think anything of it. He had been doing some things around the house and thought that maybe he just forgot to put them away.

A couple of hours later, he returned home and when he sat in his chair, he noticed a note on the end table addressed to “Dad.” The note was a plea for help. She wrote that she didn’t want to live, that she had gone to the garage to hang herself.

Matt took her to the hospital, Brianna had been cutting herself, he learned. She had cut herself in places that were hidden from Matt. She stayed in the hospital for a couple of weeks.

She was 13.

It was then that Matt learned about why she fled North Carolina. She had endured some trauma while living down south. She told people, Matt said, but they were skeptical. Nothing was being done about it. Matt also learned she also blamed him, figuring, “My dad is a former police officer. Why wasn’t he protecting me?”

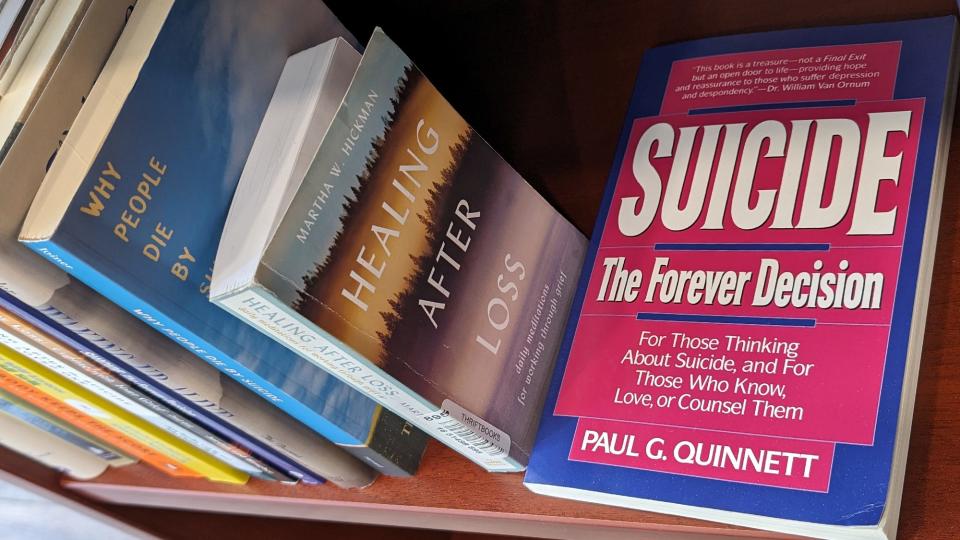

She spent time in inpatient psychiatric facilities for juveniles in Harrisburg, Philadelphia and State College. (Matt said there is a need for such a facility in York County, but none exists.) Matt turned his house into “Fort Knox,” he said. He put up motion-triggered lights. He locked up the knives and placed his firearms in a gun safe. She was still able to get her hands on razor blades to cut herself.

In October 2020, Matt said she came to him and told him she needed to go to the hospital. “I want to die,” she told him.

She went to a facility in State College for a couple of weeks. Her goal was to be home for Halloween. She loved Halloween and always dressed up to hand out candy to trick-or-treaters. She made it and for a time, Matt said, she seemed to be doing well. “She was in what I thought was good spirits,” Matt said.

She wanted an emotional-support dog, but Matt couldn’t get her doctors to sign off on it for insurance purposes. Instead, he said, he got her a puppy, a mix of Siberian husky, rottweiler and German shepherd. She was a small dog with one blue eye. Brianna named her Emma.

She took Emma for walks around the neighborhood. Matt felt that Emma gave her some purpose, that she had “something to care for and nurture.”

Around Thanksgiving, her younger brother John, who was 13 at the time, came to visit, planning to stay through New Year’s. Schools were closed by the COVID pandemic so he could still attended classes online from his dad’s house in Dallastown.

On Dec. 3, Brianna and John were downstairs in the living room, doing schoolwork and occasionally bickering as brothers and sisters do. Eventually, John went to his room upstairs, leaving his sister in the living room.

Minutes later – at 1:28 p.m. - Matt heard a loud bang. He wasn’t sure what it was. He thought maybe Emma had knocked over their Christmas tree or something like that happened. Even with his law enforcement background, he said, he didn’t recognize it as a gunshot.

Matt was in the bathroom, so John went to investigate. John returned and told his dad that he had seen smoke downstairs. Matt went downstairs and saw Brianna lying halfway on Emma’s dog bed in the living room. At first, he said, he thought she was asleep, she could fall asleep anywhere. Then he noticed his gun safe was open. Then he saw his Kimber 1911 .45-caliber service pistol on the floor and picked it up.

Then, he looked at Brianna.

“She was gone,” he said. “There was nothing that could be done.”

Brianna was 15.

There were clues

At the time, Matt said, “you have no idea what you’re thinking. Later, he said, the more he thought about the days leading up to Brianna’s suicide, the more he realized she had been dropping clues. She had told him that he should get out more and that she wasn’t going to be there forever. He thought she was talking about graduating from high school and leaving home, “not that she would be gone.” He said she told him that getting Emma “was a gift to me to make sure I had something left behind.”

The days following Brianna’s death were a blur, arranging a funeral, leaning on family. He couldn’t stay in the house. “I couldn’t even walk in the front door,” he said. He wasn’t going to be able to live there anymore.

For weeks, he said, he fell into a deep depression. He even thought about ending his own life. He needed help.

'I could make a difference'

Twenty-four days after Brianna died, family and friends were helping Matt clean out his house. “The only room I wanted to do was Brianna’s room,” he said.

As he cleaned out her room, he was getting angry. “We started talking,” Matt said. “We had to do something.”

He found a T-shirt of Brianna’s. It’s white with blue script on its front saying, “Keep fighting. I believe in you. You are a star.” (The shirt now resides in a frame on the wall of Matt’s office.)

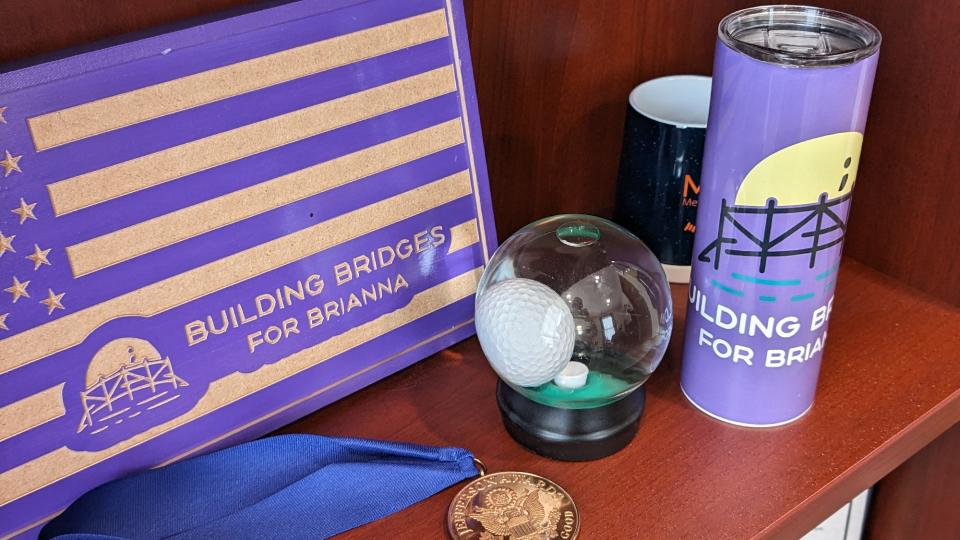

Matt and his family and friends were talking about what to do, perhaps a fundraising event to benefit mental health agencies serving people in crisis. One person mentioned, “We need to build a bridge between the people who need help and people who can help.”

The first event of what would become Building Bridges for Brianna was July 26, 2021, at the Dallastown Community Park. About 1,500 attended. They had music and food and people to provide information about seeking mental health treatment in the community.

Matt spent a good part of the day talking to others who had lost family members to suicide. “They know I totally understand what they’re going through,” he said. “There’s a connection.”

It soon became apparent that it was not going to be a one-and-done event, Matt said.

He was thinking about that, and about Brianna, while he was cleaning up after the event at the park. He was alone in the park and was having some dark thoughts. He felt maybe he should just fade away. Then, he said, friends started showing up to help.

They didn’t talk. But the message was clear to Matt.

You don’t have to be in this thing alone.

“I saw that I could make a difference,” he said. “But I can’t do it if I’m gone.”

'It's OK not to be OK'

Building Bridges for Brianna recently moved into a new office, in the old bank building on Main Street in Dallastown, above a Thai restaurant.

The organization outgrew its former office just north of town. It started small, helping people with co-pays for mental health services and paying for medication when insurance fell short. It referred people to therapists who could see them right away instead of placing them on a waiting list. They’ve helped a lot of people and have found therapists for about 60 people. The effort also seeks to dispel the stigma surrounding mental health, that mental health care is, simply, health care. It earned Matt a Jefferson Award this year.

Among its fundraisers is selling purple light bulbs. One burns 24-7 at Matt’s house. He got the idea to sell the bulbs as a fundraiser and ordered 20 of them on Amazon. They sold out in minutes. He ordered another 20 and they sold out. During that fundraiser, the organization sold more than 400 purple light bulbs, and you can see purple lights shining through windows throughout the community, Matt said. “It means something,” Matt said.

The new office has space for a therapist’s room and other amenities. His employer, Dollar General, is generous with its support, allowing Matt to work from home or the Building Bridges for Brianna office.

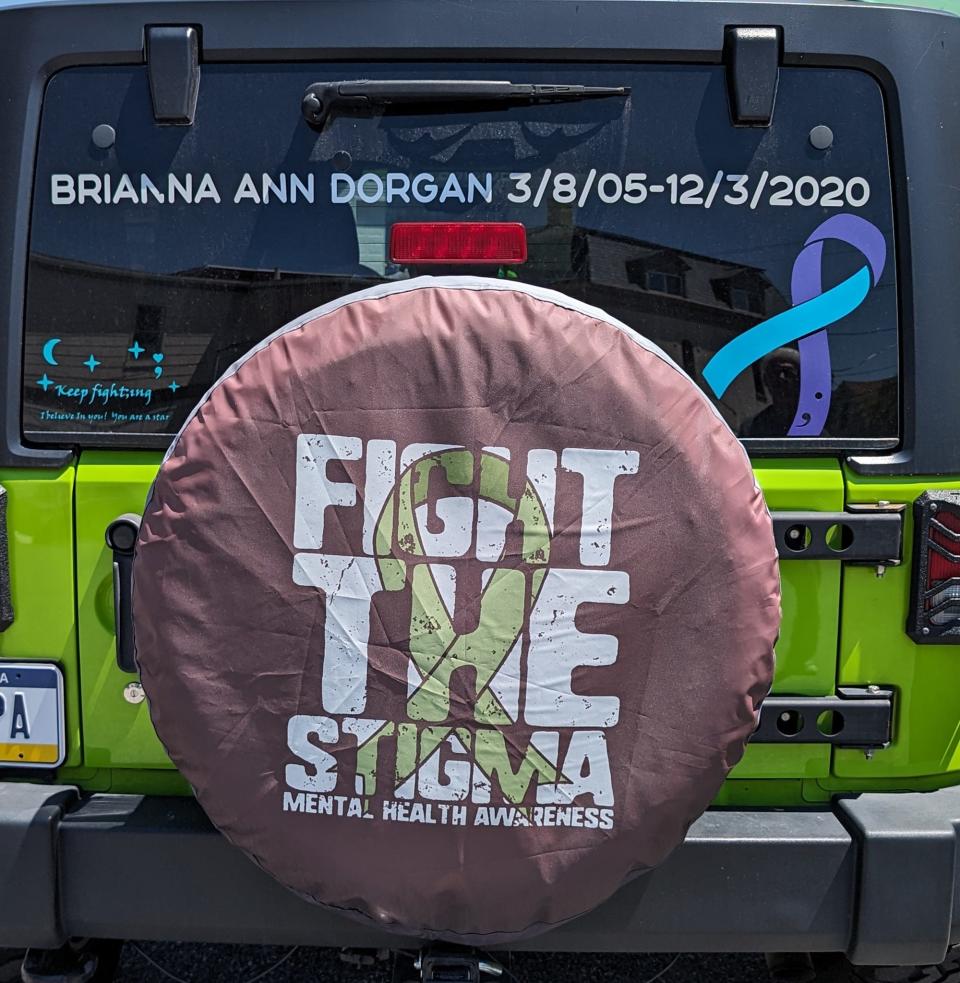

Not long ago, he got a new four-door Jeep, lime green. Brianna loved Jeeps and loved green, Matt said. The Jeep is festooned with messages about Building Bridges for Brianna.

The most important one being, “It’s OK not to be OK. We just can’t stay that way.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at mike@ydr.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Building Bridges for Brianna works to prevent teen suicide