Dakar Fashion School Trains New Generation of African Designers

PARIS — African fashion is enjoying a renaissance as a new generation of designers captures the imagination of luxury brands and consumers. But while the continent is rich in creativity, most brands have found it challenging to grow beyond their borders due to a lack of formal training.

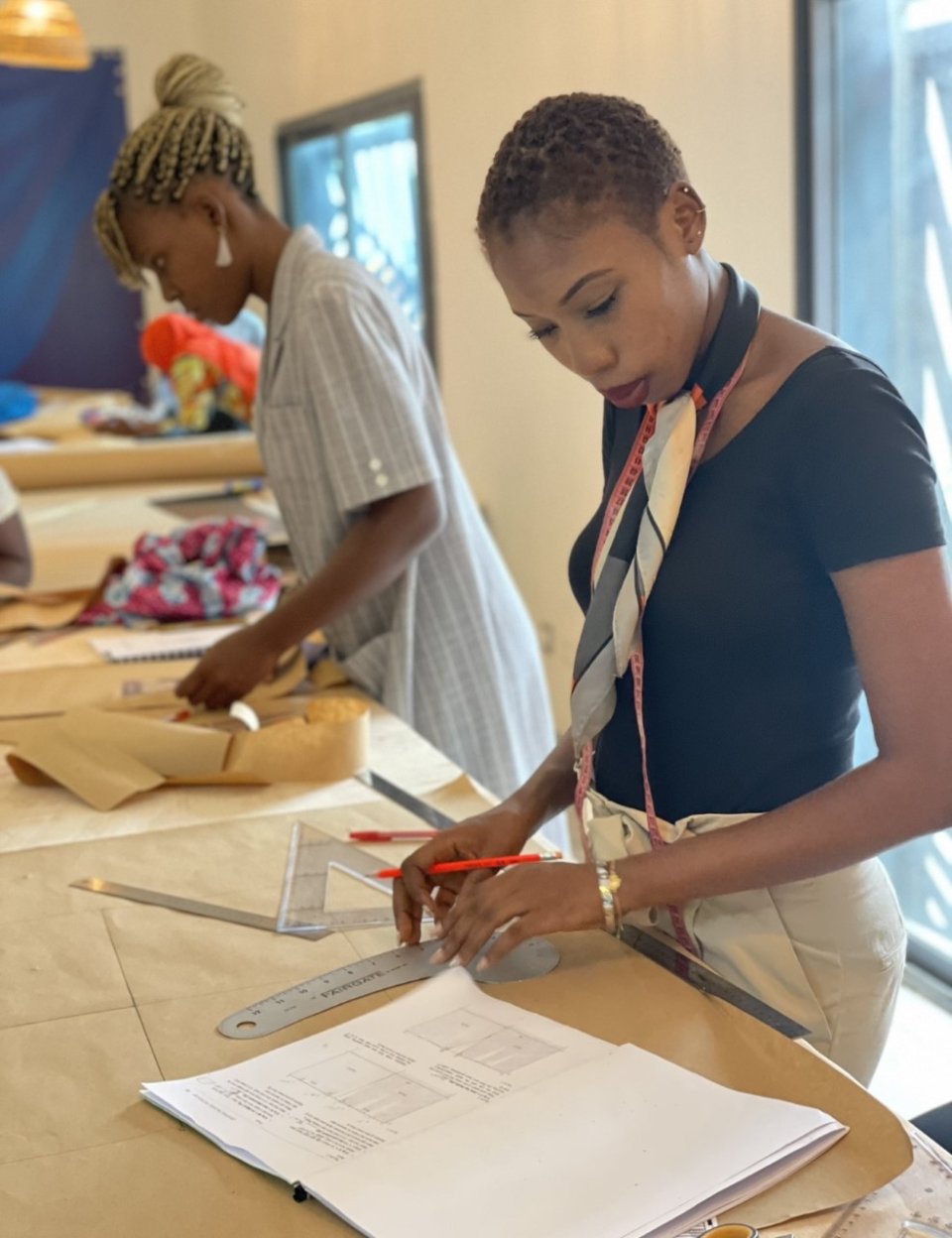

That’s the assessment of Sophie Nzinga Sy, a Senegalese designer who has opened the Dakar Design Hub, a training facility that provides courses for budding fashion entrepreneurs and local tailors alike.

More from WWD

Nzinga Sy launched her Sophie Zinga brand in 2012 after studying fashion design at The New School’s Parsons School of Design in New York City, having dropped out of her earlier economics studies at school.

“I opened my first store in 2013, started trying to recruit from different design schools like you would normally do and just looking out for factories who could develop my collections. And I had a really hard time and it was like an awakening for me,” she said.

“I literally couldn’t believe it because for me, Dakar is one of the fashion capitals [throughout] Africa, so I thought that it would just be easier to find an assistant fashion designer or a patternmaker and it was really, really difficult. And the more I traveled across the continent, whether it was in Ghana or Nigeria, I would speak to my colleagues and they would say the same thing,” she said.

“African fashion was getting a lot of buzz, but I think the missing link was quality fashion education across the continent and especially in Senegal. And so in 2015, I started ideating.

“It was more at first just a fashion school that I was thinking about launching and then as I went through and I looked at the ecosystem and I looked at all the different things that I needed support in, I thought about having a hub that would just have different components and support younger generations,” Nzinga Sy recalled.

The campus, an hour outside the Senegalese capital, was formally inaugurated a year ago and began offering courses in February. The school is starting small, with 50 to 100 students expected to attend in the first year, but it hopes to eventually welcome between 250 and 500 students annually.

“We have different target audiences. Our main target audience is our fashion entrepreneurs who basically have their own brands, already have a shop or are selling online but need the tools to understand better what they’re doing as far as business but also looking at the fashion design elements that they never really had the chance to learn in school,” she said.

Those courses last anywhere from two weeks to six months.

“Secondly, in 2024, we’re going to be launching degree programs, so we’re going to be looking into high school graduates who are just interested in fashion design and who want to study fashion.

“And then our third audience is tailors and professionals who work in the fashion industry, patternmakers and machine technicians who need to upskill what they already know in order to better serve the entrepreneurs and maybe work for factories,” she explained. “We’re building slowly our curriculum, which will lead us to higher education and not just professional courses.”

Thanks to word-of-mouth, Nzinga Sy recruited an international faculty with teachers from Senegal, the U.S., The Gambia, Canada and France. “It’s just been really a big melting pot of different people who are experts at a very high level,” she said.

She noted that Patricia Blackburn, the fashion program director, has more than 20 years of experience working in Hong Kong, the U.S. and Canada. “The idea is to really make sure that whatever we’re doing and teaching, it really aligns with the global fashion landscape today,” she said.

Nzinga Sy is also bringing to the table her own experience as an entrepreneur. Between 2012 and 2017, the Sophie Zinga brand produced seasonal collections and staged fashion shows in Milan, New York City, Paris, Dubai, Lagos, Nigeria, and Johannesburg, South Africa, in addition to Dakar.

“I believe I was the first to kind of dabble into luxury ready-to-wear in Senegal,” she said. “The conclusion was that there was a certain niche in Senegal, across West Africa, of people who really, really wanted to buy luxury African fashion, but it was a very small niche.”

With outfits priced from $200 to $2,000, the label used imported fabrics, an approach that ultimately struck the designer as costly and unsustainable. “And so it was about, how do I redefine Senegalese luxury? And through that I started thinking about a more contemporary brand that would speak more to the new African consumer,” she said.

She paused the Sophie Zinga brand in 2017 and came back in 2019 with Baax, a more accessible label focused on sustainability.

Nzinga Sy showed her new collection on Saturday as part of Dakar Fashion Week and will present her designs at London Fashion Week for the first time in February as part of a showcase for African countries organized by the British Council. The organization, which specializes in international cultural and educational opportunities, has also provided funding for the Dakar Design Hub.

“I struggled a lot finding the finances for this because back in 2015, in Senegal, people didn’t really take fashion or the creative industries too seriousIy and so it was really hard to explain the project and I had to go through different doors to have access to finance. The banks had no interest in financing something like this,” Nzinga Sy said.

She sold a house she owned for seed money and eventually obtained a $50,000 loan from the Délégation Générale à l’Entreprenariat Rapide des Femmes et des Jeunes, or DER, a government entrepreneurship institution that helps small- and medium-sized companies.

The German Agency for International Cooperation, known as GIZ, provided funding for salaries, machinery and other costs, but Nzinga Sy is on the lookout for additional partnerships. A team from Chanel, which is preparing to show its Métiers d’Art collection in Dakar on Tuesday, recently visited the premises.

“I always say that the Dakar Design Hub is a social project. It’s not a project that will make money in the next coming years. We’re trying to structure the industry through education in Senegal and so that’s a really, really difficult, an ambitious feat. And so in order to do that, we really need more support in terms of human resources but also finances in general,” she said.

Thanks to existing donations, the school has been able to provide some free courses, as well as handing out seed loans through a pitch competition.

“We’re looking to partner with different institutions, international fashion schools, but also foundations who would be interested in giving out scholarships,” she said. “A lot of those students who are interested in fashion can’t afford to pay for the student fees and so our big next step is to be able to roll that out in 2023.”

Nzinga Sy said her experience has taught her the value of a formal fashion education.

“I got the foundation that I needed as a fashion designer to be able to start my brand as a young 23-year-old,” she said. “Ten-plus years ago, African fashion was still buzzing and still new and I think just having Parsons on my CV was really helpful in navigating different spaces.”

Yvonne Watson, the interim dean at Parsons, helped her to develop the curriculum for the Dakar Design Hub. “She was the curriculum dean when I was in school and so we developed quite a great relationship,” Nzinga Sy said. Still, she’s keen for the institution to stand on its own two feet.

“We’re really trying to build our credibility as the Dakar Design Hub and as a fashion school and then later down the years, I think it would be beneficial to have a name like Parsons or Central Saint Martins as an exchange partner,” she said.

Nzinga Sy believes partnership is key to unlocking the potential of the African continent and should benefit all sides.

“There’s just this hunger for African fashion because of the creativity that’s just been untapped and I think, if we are to look inwards and think about what a new fashion means for the global fashion industry, we have to collaborate and we have to work together,” she said.

“Obviously, there’s a huge consumer base in Africa that is untapped. Almost a billion people live on the continent and so that’s already something that’s just a huge opportunity for not only African fashion designers but also global fashion brands,” she concluded.

Best of WWD