Dads Without Dads: Absence and Presence on Father’s Day

My father died the day I graduated college. As tragic as that may sound, he was long gone from my life by then.

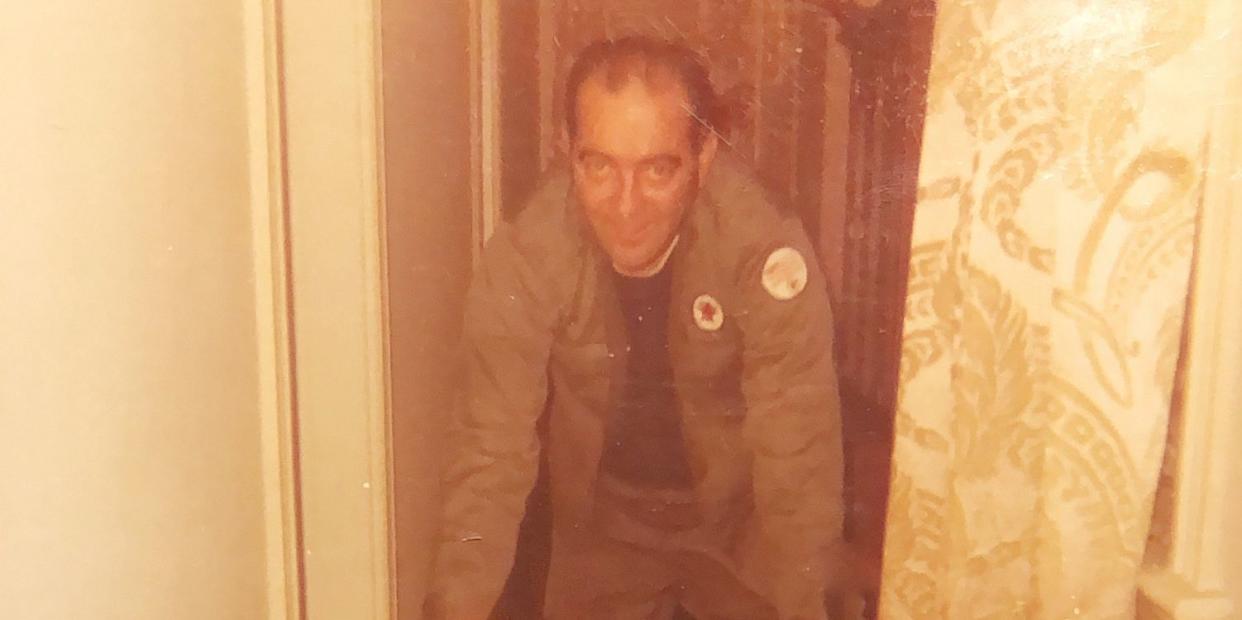

My memories of him are few: A man in a Texaco jacket helping me walk across the linoleum floor in the kitchen of our Chelsea, Mass. apartment. Later taking me to see Alice in Wonderland (the Peter Sellers movie not Johnny Depp.) That’s about it.

For most of my life, I was led to believe that my father fought and lost a custody battle for me. Only to lose touch with us once my mom remarried and moved to rural Pennsylvania. Like other kids in my situation, I imagined a grand reunion of sorts. One day, he’d find us and we’d have a catch—or some other trite, Rockwellian father-son moment. I even wrote a little diddy, that I would sing when no one was listening. It was set to the melody of “Here Comes the Sun” (apologies to George Harrison.)

“Where is he now?

How is he now?

Am I ever going to see him again?”

I can still see my twelve-year-old self singing that song—on the top of my bunk bed, walking at night in our trailer park, playing catch with myself against a brick wall. Pathetic, right? The dream of that song ended temporarily when my mom said she heard my father died in an explosion. It ended permanently when at the age of thirty-five, I discovered the truth; he had died of colon cancer the day I walked to receive my diploma years earlier.

His widow subsequently told me that he had never mentioned to her or anyone that he had a son. There was never any custody fight or even acknowledgment of my existence. The only legacy left for me would be a lifetime of colonoscopies—which, to be fair, probably saved my life. The absence of a father for a son has too many drawbacks to enumerate. One comic illustration: When my mother bought my first baseball glove, she incorrectly assumed being left-handed meant the glove should go on my left-hand. So I threw with the wrong arm for the first three years of little league.

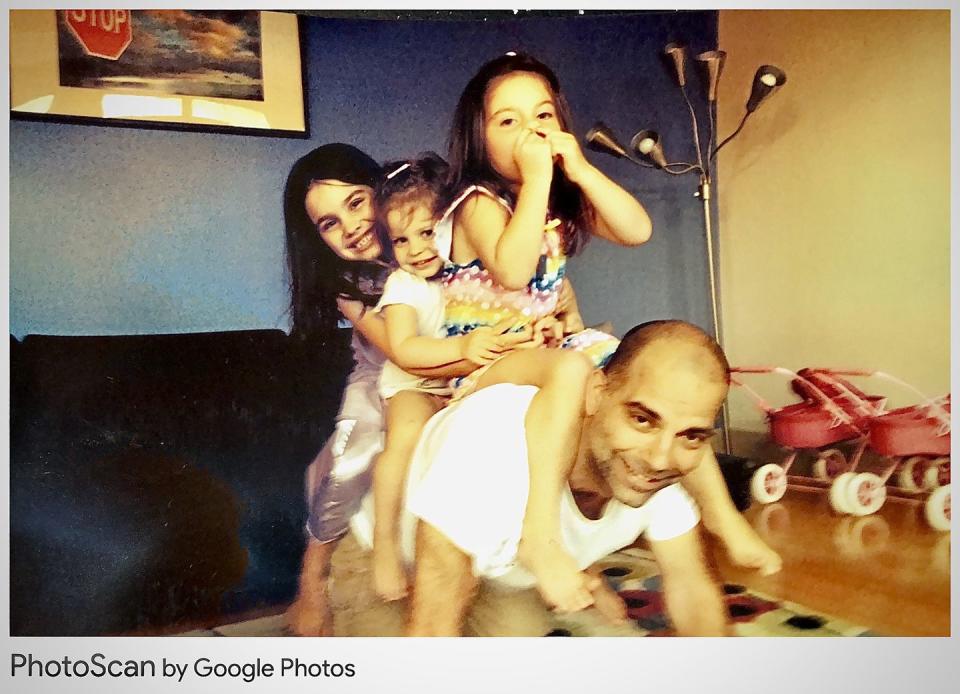

I have no recollection of ever calling someone Dad or Daddy, but now with three daughters of my own, it is by far my favorite word to hear. My children did not come into the world easily. There were many moments when I did not think I’d ever become a dad.

On the night when the first of my three daughters was born, I found myself alone in the shower, sobbing uncontrollably. The last time I sobbed like that was when I learned my father had died. The duality of fatherhood expressed in salt and water. For those dads, like me, who now live without a father, Father’s Day can be a bittersweet day. It is one to reflect on profound loss and ultimate gain; one of absence and presence.

The absence of a Dad comes in many forms. They may be physically present but emotionally unavailable. There are separations of distance or divorce. Falling outs or moving ons. They may have given up their child for adoption or taken on a new family. Or died prematurely. Today, one in four children live without a father in their home. As an adult, I am now of the age where each year several of my friends lose their father. The “Dads without Dads” club is growing.

In preparing this piece, I talked with several of my friends about what it’s like being a “dad without a dad” on Father’s Day. Even though they are amongst my longest and best friends, it was often the first real conversation we had about our relationships with our dads and our kids. Not shocking given how much guys like to “share their feelings” with each other. All were unified by their absolute love of being a father and complicated feelings in describing their own relationship with their dad. So Father’s Day is like a full heart with a small leak. Most recounted their ambivalence around Father’s Day growing up while emphasizing their appreciation of it today.

Since graduation, my friends have been returning to college for a charity golf weekend that we nonchalantly scheduled over Father’s Day weekend, obviously before any of us were fathers. We were completely comfortable to nurse our hangovers on Father’s Day rather than nourish our connections with our own Dads on their day. As more of us became fathers ourselves, our tunes changed. Sunday mornings would see us rise early in the morning to rush home to our waiting children. Time, not ties, is the gift we cherish most. Perhaps an attempt to overcompensate for our father’s absence with our presence.

As a reflection of how much often goes unsaid between fathers and their children, most of my friends wished they could have another chance to talk with their Dads. Some, myself included, wanted to ask questions to better understand why our Dads did what they did (like leave us). Or conversely to own the pain they unintentionally inflicted on their fathers (those teenage years!). Others, reflecting on their own failings, wanted to tell their dads that only now can they really appreciate the demons they must have faced when they were younger (ranging from battling alcoholism to work and financial pressures).

And of course, there are also the simplest of desired conversations, too. “When I was younger we didn’t share our feelings much, and by much I mean never. I wish I could just have another chance to say, “I love you.” To be clear these were not conversations of closure but openings. Many actually have these conversations on Father’s Day, in their heads or in front of headstones that cannot talk back. We ask for advice and understanding and instead find silence and a semblance of peace.

The juxtaposition of the presence of our children on Father’s Day and the absence of our Dads is particularly poignant for one friend. This year he will eulogize his dad just days before celebrating Father’s Day with his two children. Knowing that I wrote a modern retelling of the children's classic The Little Engine that Could, he sent me a picture of his father reading the original to him in bed when he was a little boy. Recently, he read that same story to his father on his deathbed. So goes the circle of life.

For most, the juxtaposition of being a father without one is not as stark. But it only takes a moment’s reflection or a simple question to get there. So on this Father’s Day, let me first state the obvious. If your Dad is still with you, go beyond the perfunctory phone call. Ditch the tie and find the time to really talk with him. If, like me, you’re a dad without a dad, take a moment and tell your kids a story about your father and let your children know just how much being their father means to you, and why.

Finally, when the day is winding down and your kids are fast asleep, call a “dad without a dad.” If your conversations were anything like mine with my friends, your fathers will come to life again if only for a few minutes. And what a wonderful Father’s Day gift that would be—from one dad without a dad to another.

Bob McKinnon writes the Moving Up Mondays blog, is host of the PBS podcast, Attribution with Bob McKinnon, and author of the forthcoming children’s book, Three Little Engines.

You Might Also Like