My Dad Made Me Feel Beautiful

If you'd asked me 20 years ago what it was like to have a physical disability, I would have said something like, "Well, it's certainly not easy to blend in." I was a teenager, and the last thing I wanted was to stand out. But I felt as if a giant spotlight followed me everywhere, illuminating every surgical scar and deformity. Surprisingly, I would eventually find my sense of beauty and belonging in an unexpected way: shopping with my dad.

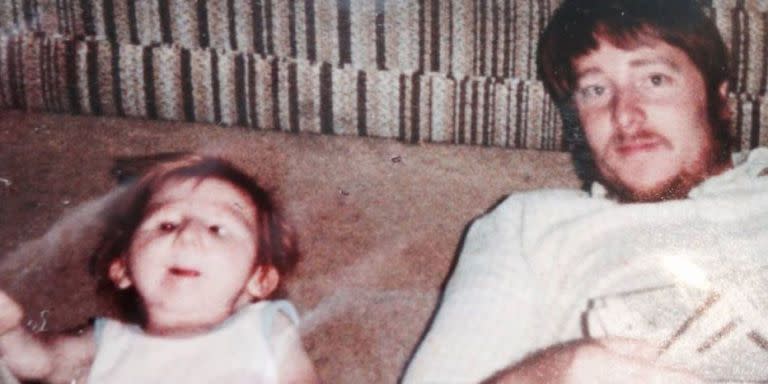

I was born with Freeman-Sheldon Syndrome, a rare genetic bone and muscular disorder. I had joint contractures in my hands and knees (both knees were frozen at 90 degrees), a small mouth, scoliosis and a cleft palate that made swallowing so difficult, bottle feedings took more than an hour.

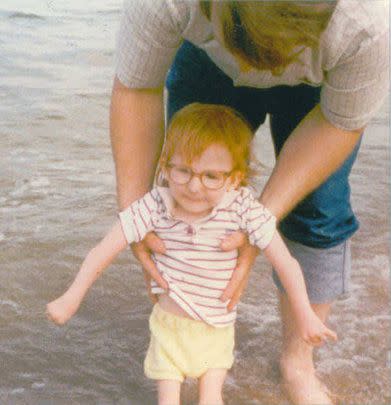

My childhood was a revolving door of doctors and hospitals; I had around 25 surgeries, usually involving a contraption called an Ilizarov, a metal frame around my knees with pins inserted into the bone. (A series of adjustments slowly straightened my legs.)

At 13, I had my most serious surgery after doctors discovered my spine was compressing my brain stem, severely weakening my swallowing reflex to the point where I couldn't eat. My weight plummeted to 49 pounds - at just 3 feet, nine inches, I felt as if I was shrinking. Throughout those scary years, my family was always by my side. At night, my mom slept on a hard recliner next to my hospital bed. During the day, my father was my constant companion, taking me on "adventures" to the cafeteria and reading to me in his soothing voice when I got tired. As odd as it sounds, those were some of my favorite childhood memories. They were also the first times I got to bond with my dad. He somehow made the hospital less frightening, and he took on this superman, larger-than-life persona in my eyes.

Shortly before my 15th birthday, I had my final surgery, a knee fusion (joining the thighbone and shinbone to create a more stable joint), and with it I arrived at a major turning point: At last, I thought, I could live a more "normal" life, one that didn't revolve around medical crises, though I didn't really know what that would mean. I'd grown up surrounded by the white walls of the hospital, and I felt more comfortable with doctors and nurses than with kids my own age. I had a core group of friends, but I'd never had a sleepover or gone shopping with them or been to a school dance. It all made me feel like a fish out of water, as if I had years of experience to catch up on with no idea where to begin. In the hospital, I belonged. In the halls of high school, I felt like an outsider.

All along, my parents had made every attempt to help me live a normal life. Since my tween years, I'd been in hot pursuit of anything cool and chic that held the promise of transforming my disabled self into my hometown's Brenda Walsh (of 90210 fame). I dove into the fashions of the day: snap bracelets, butterfly clips, nail polish and lipstick in my favorite color, hot pink. I'd check out issues of Cosmo and Glamour from the library, eager to try out their beauty tips in my room the minute I got home. If I could just wear what everyone else was wearing and look like them, I thought, then maybe I could hide everything that made me feel so different. At the very least, maybe my disability would no longer be the first thing people noticed about me.

When I was around 10, my dad and I started what became our tradition: Whenever I was sick (I was prone to ear infections), we would check out the makeup in the drugstore while we waited for my prescription to be filled. I'd zoom up and down the aisles in my wheelchair, exploring this enchanted world I'd only ever seen in magazines. Invariably, my eyes would go straight to the lipstick section, where I'd run my hands over each tube of glossy lipstick, asking my father for his expert advice on my selection.

"What about this one?" I'd ask, holding up a tube of deep maroon or neon orange. My young, eager self was pretty sure I could pull off anything.

"Oh, that's a nice shade," he'd reply without missing a beat, an earnest smile coming across his face as if he'd thought long and hard before answering. After looking at the rainbow of other colors available, I usually settled on some bright, out-there color, the lipstick acting as a sort of get-well gift.

As I got older, our tradition grew. My father became my retail wingman when my family went to the mall. My mom and sister would go see a movie while he and I walked around, spending an entire afternoon exploring every bookstore and shop, and he'd carry all my bags as I browsed the racks just like everybody else. I remember our having some of our best talks in the food court and whileflipping through CDs in the record store. I'd tell him how much I despised high school chemistry or why 'N Sync was so much better than the Backstreet Boys. Our conversations weren't earth-shattering, but as I matured, I began to realize maybe that was the point. For once we weren't bogged down by weighty talks with doctors or making frightening life-or-death decisions. My father showed me that I could exist in the real world - a world completely removed from my medical past. I could be myself. That girl who'd had 25 surgeries? She didn't have to be my whole identity anymore. Suddenly, talking about mundane things like my favorite ice cream flavor seemed incredibly important.

He was the sort of dad who really listened to what I had to say. He seemed happiest when we were spending time together. My friends told me their dads would groan at the thought of piling into the car and taking them to the mall on a Saturday afternoon, but my father relished the idea. I always say that he was a metrosexual before that was a thing, and that it was his contentment and level of comfort with himself that taught me about loving myself and not being afraid to be who I am.

Looking back, maybe my father's bonding traditions were really a lesson lesson in disguise, one that began with the two of us in quiet hospital rooms and continued under the bright lights of the makeup section. I learned that it doesn't matter if you have flowing blond hair, smooth skin or scar-free legs. In the end, that's not really what people see. And it's certainly not what they'll remember about you.

What matters most are your words, your actions and your strength of character. Who you are, not what you are - that is the real definition of beautiful. Because when you strip everything away, all the lipstick and nail polish, what you're left with is your true self. And that, my dad showed me, was something to celebrate.

I lost my father in 2003, just as I was starting to brave the world on my own. Today, at 35, I have long since made the transition into living a more normal life. And I don't need to cover myself with makeup anymore. The lessons from my father will stay with me far longer than any lipstick ever could.

This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of Good Housekeeping.

('You Might Also Like',)