I’d Never Even Heard of Bite House, Now I’ll Never Forget It

This article is part of a series on Canadian food and travel, with support from Destination Canada.

Levon Helm’s falsetto runs over every surface in the Bite House kitchen, as the Band’s harmonies play from a small but capable speaker on the top shelf of the glassware cabinet. Bryan Picard sets down his coffee and looks up from a quarter sheet tray filled with cornflowers, fennel fronds, apple mint, and shiso leaves that he picked from his garden about three minutes earlier. “We should go drop this off at Bill’s house,” he says, tapping the five-gallon plastic bucket of wonderfully fragrant crystalized honey monopolizing the right side of the counter. “Bill’s great. He’s, uh...a bit of a hippie. But he grows really beautiful dill.”

On the short drive to Bill’s, we hop out of Picard’s small hatchback and hurdle a ditch on the side of the empty dirt road to pick chanterelles from a damp, mossy patch that Picard somehow spotted under some birch trees. “I always leave the little ones,” he says, slicing the larger golden funghi at their bases with his Opinel knife. “You have to let them grow. I only pick exactly what I need. We’re not here to take everything.” Back in the car, I think about the broader significance of that ideology as we dodge potholes on Bill’s long driveway.

I’m not in Picard’s car by chance. I’m there because a friend from Toronto told me about a small restaurant in the middle of nowhere, on Nova Scotia’s eastern-most island, that was inescapably alluring. It’s impossible to get a reservation. The chef is amazing. It’s in a little farmhouse. It’s called the Bite House.

Picard’s restaurant is open three days a week from May to December. The kitchen’s four-burner stove is electric. The coffee is made in French presses. There are 16 seats, four employees including Picard, 35 herbs grown in the garden, a 200-song playlist filled with deep-cut blues and country tunes, two beers on tap, and a dog named Chester. There is no automatic dishwasher, just a small kitchen sink. And about an hour after Bite House opens its dining slots for the year, there are no reservations left.

It’s a restaurant that I absolutely should have known about years ago, or at least more than a month before I walked up to Bill Shelley and shook his hand.

Shelley is, as advertised, a bit of a hippie. The 72-year-old American has a long white ponytail that’s only half as impressive as his garden, which erupts from the Canadian hillside with peas, corn, tomatoes, poppies, squash, herbs, and the odd patch of black-eyed Susans in front of the shingled house that Shelley built on the property decades ago. While staring at the magnificent shades of green, listening to Shelley tell the story of how he lived in a school bus on the property in the ’70s, and feeling the late summer air, the thought of a harsh Canadian winter is inconceivable.

“He’s a great neighbor,” Picard says. “Sometimes he’ll just stop by with vegetables or herbs and ask for a beer in return. He lets me pick whatever I want from his property and use it at the restaurant.”

The restaurant is located in Big Baddeck—a town far more abundant with single-lane bridges and river bends than it is residents—in the center of Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island, a three-hour drive from the Halifax airport. The Bite House is both Picard’s restaurant and his home, which he shares with his girlfriend, Marie Isabelle Whitty Lampron, who operates a shop for her clothing label, Whitty, at the front of the property.

At the top of the driveway lies an old red dairy barn, three small sheds (one filled to the brim with chopped wood), a dozen garden beds, and the foundation for what will soon be Picard’s wood-fired oven and outdoor bar. The white farm house, located in the center of the property, is where Picard and Isabelle design clothing, cook, and live.

Back in the kitchen, Picard blanches the dill and some spinach, mixing it with oil in his Vitamix. He shells fava beans and makes honey fudge, a chewy, floral caramel with a two-to-one ratio of sugar to honey. He removes braising liquid from a Dutch oven that’s held a pork shoulder since sunrise, reduces it in a separate pot, then pours it back into the pot. He grills cabbage and radicchio in the wood shed outside. He stamps the cover of each of the evening’s menus with a contour line drawing of the building in which we’re sitting.

It’s all incredibly surreal: The property. The produce. The music. The neighbors. The complete lack of...restaurant-ness attached to one of the most in-demand, well-regarded, isolated restaurants in North America. Coming from New York City, I assumed that Bite House would be a welcome break from the structure and pretense of the metropolitan restaurant scene, but three hours into hanging out with Picard and Whitty Lampron, I realize that this place is not only different from the restaurants I usually eat in; it’s different from any restaurant I’ve ever eaten in. I walk outside and ask myself: What exactly is happening at Bite House? Who is eating here? What is this place? And who is this guy in the kitchen?

For a restaurant that sells out for the year in a matter of minutes, Bite House is unassuming and, honestly, slightly underequipped. Picard cooks. Whitty Lampron runs tables and serves drinks. Picard’s father, Moe (who has retired from his job at a paper mill in New Brunswick), does the dishes and helps plate during service. Picard serves nine courses staggered between a single seating. On paper, with the kitchen in mind, the whole concept is borderline ridiculous. Possibly even—to those familiar with the logistical workings of a restaurant and those in touch with what it takes to serve world-class food—impossible to pull off.

“The first year we opened, it took about three months for the reservations to book up,” Picard says. “The second year, it was one month. And for the last four years, they’ve all gone within the hour we post them. Over the past six years, there have only been two nights where the dining room wasn’t full.”

The night I’m there, the COO of a large home goods company in Manhattan is eating at Bite House with three of her friends. And Maggie Gyllenhaal—who vacations on the island—was supposed to come in as well, but her flight was delayed. “It’s about 75 percent locals that eat here. The couple at that table come in once a year. Their parents were in last week,” says Picard, who then turns toward a large flannel-clad man with a white beard. “That’s Stemer. He’s from Baddeck and comes in once a month. You’re actually staying in his house this weekend.” The man gives me a nod, as I realize I still have to pay him for my lodging. Every time a new guest enters the house, Picard stops what he’s doing in the kitchen and walks into the main room to greet them.

And that sentiment extends past the patrons. If you look to the left of the front door, you’ll see a list of producers in Cape Breton and Nova Scotia on display. Bill Shelley’s name is there. Michelle Bona, the woman who produced the massive bucket of honey we dropped at Bill’s house, is also there, among other local farmers, dairy producers, and fishermen. Picard pours me a wild-fermented, single-varietal cider made by Sourwood Cider in Halifax and starts plating.

Dinner is phenomenal. It starts with small plates that Picard calls snacks. Some are involved: halibut cheek with ginger mint and savory blossoms, served on a nasturtium leaf. Some are simple: bread—a single slice of sourdough, made with grains grown exclusively in the Maritime regions of Canada, served with butter and bee pollen—of which Picard and his father bake only two loaves a day. Dense, warm, and barely tangy, it is unlike the holey, sour, crusty-as-all-hell loaves that dominate restaurants and bakeries in the States. It’s the best bread I’ve tasted all year.

The staff speaks French in the kitchen as they sing and joke with one another during service. Picard turns to adjust the levels of the stereo as the music changes from Johnny Cash to Charles Bradley, playing chef and DJ simultaneously. It is, in short, impressive.

As dinner moves to the more substantial dishes, the ingredients that we plucked and trimmed and grilled and blended during the day become more prominent. The dill oil is drizzled over charred radicchio we grilled in his shed and topped with chicken confit, salted cream, crispy shallots, and apple mint. The fennel fronds and cornflowers we picked from Picard’s garden are sprinkled over birch-smoked mussels in milk broth with fava beans and sea parsley.

The savory portion of the meal ends with braised pork shoulder, grilled cabbage, oregano from the garden, buttered chanterelles we foraged that morning, and red currants from Bill’s driveway, all topped with braising liquid—reduced for the third time—and a dusting of maitake powder. The umami is monumental.

To finish, Picard slides a shallow bowl of lemon balm ice cream with strawberries preserved in wine syrup, topped with deeply toasted meringue and hazelnuts and a few carefully placed pickled rose petals across the counter. The layers of sugar, fruit, acid, and fat inspire a sense of mild rage. I realize I won’t be satisfied with any other ice cream dish for quite some time.

After the plates are cleared, I order garden tea. A glass kettle arrives, packed tightly with vibrant green leaves and stems, yellow and purple flowers. It’s filled with every herb that grows in the backyard, a tsunami of sweet, savory, herbal flavor that is less about nuance and more about letting the entirety of the garden wash over you. The tea seems to explain everything you need to know about Bite House: They grow things, and they give them to you. That’s it.

As guests begin to leave the house, they offer excited compliments. One man drops off a bottle of fermented pineapple-habanero hot sauce he made. Picard smells it, smiles, and opens one of the kitchens two small fridges, pushing a bottle of French red to the side to make room. “It actually smells really good,” he says to me after the customer leaves.

The following day is Picard’s first day of his two-week vacation. We drive north for lunch, up and down cliffs that line the Atlantic coast. We stop at a small store called Leather Works by Jolene to buy a few leather sleeves to use as check holders at Bite House. “How’s everything at the restaurant? How’s the season treating you?” asks the woman behind the counter.

An hour later we arrive at the Periwinkle Café in Ingonish, where we eat snow crab breakfast sandwiches on homemade English muffins and drink flat whites. Picard talks to co-owner Sarabeth Drover, who tells us that two employees are leaving at the end of the season and staffing the café is going to be a challenge. Picard is sympathetic, but I know it’s not a problem he has to worry about. Out back we talk to employee Rosie MacKenzie. “She’s an unbelievable fiddle player,” Picard says, as we walk back to the car. “One of the best on the island.”

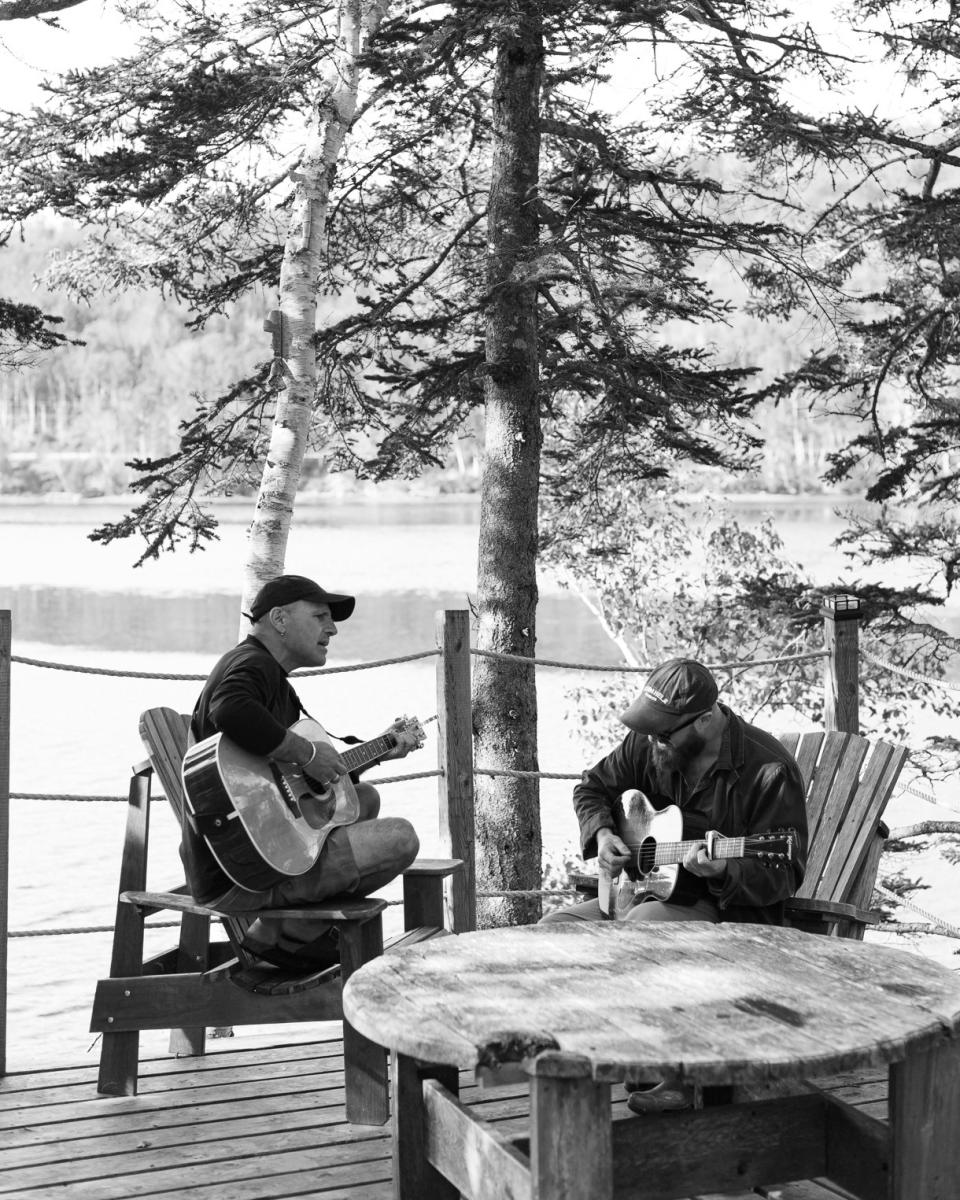

Picard’s friend Angelo—who runs a kayak tour company in the area called North River Kayak Tours—texts him, I’m around this afternoon. Bring your guitar and some beers. We grab a 12-pack of cheap Canadian lager from the only liquor store in a 25-mile radius before taking residency in two Adirondack chairs on Angelo’s dock. They each pick up a guitar and play a fantastic rendition of J.J. Cale’s “Cajun Moon,” as tired kayakers hoist themselves out of the North River. They play for hours, and as we’re leaving, Angelo hands me a copy of the album he and Picard recently recorded.

As we make our way back into cell service, the twang of Tom T. Hall’s “That’s How I Got to Memphis” rolls over the car speakers, and Picard says, “It might have been the weather or the music...but that beer was great.”

He says it appreciatively, and as he does, I remember Picard telling me about his résumé earlier in the afternoon. “I cooked for six years in Montreal and got burnt out. I moved out to Cape Breton Island and cooked for two years at a restaurant attached to a small inn. And I’ve been running Bite House for the past six years.”

To be completely honest, I was expecting Picard to be jaded or, at the very least, a bit of a dick. Those are symptoms of prolonged exposure to the restaurant industry, especially when you’re the chef-owner of a highly regarded restaurant hundreds of miles from any other chef of your caliber. For the past 36 hours, I thought I might be projecting the severe Canadian-ness of the entire situation onto him, but as he smiled about the afternoon on the dock, my growing suspicion was confirmed: I could keep looking for Picard’s ego, but I wouldn’t find it.

Back at Bite House, Whitty Lampron is wrapping up the opening party for her store. At about 10 p.m. she and her friend Kathleen Darling, who owns and operates mobile sauna Darling Banya, drive 20 minutes to get a pizza from Baddeck’s premier (and only) slice shop. They return with a pie topped with olives, bacon, and peppers. It’s good in the way that just about any pizza is good after your third glass of wine. We drizzle the fermented hot sauce that was gifted to Picard over the slices.

“You know, they’re open seven days a week,” Picard says, after finishing a slice. “Until 11 p.m. Even in the winter. In such a small community, we’re so lucky to have this.”

As he said that, I pictured every single piece of food—foraged, grown, traded for, or purchased—that he and his family serve and care for at the restaurant and had only one thought: The locals. And the farmers. And the winemakers. And the neighbors. And the fishermen. And the tourists. And the beekeepers. And the ceramists. And the people I’d met. And every other person on Cape Breton Island I hadn’t. They all better be saying the same damn thing about Bite House.

Want more on Canada? Right this way!

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit