'Curse tablet' with oldest Hebrew name of god is actually a fishing weight, experts argue

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A lead "curse tablet" written in ancient Hebrew more than 3,000 years ago may actually be a fishing weight with no discernible writing, new research suggests.

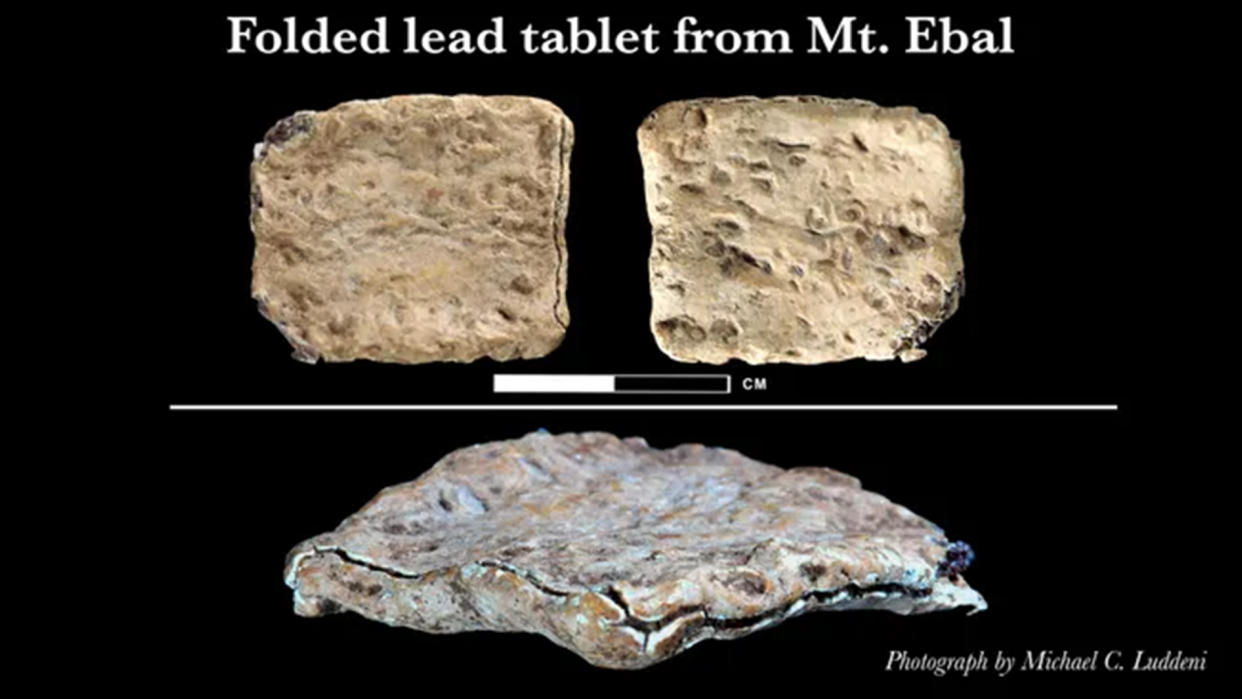

The postage stamp-size lead piece, known as the Mount Ebal tablet, has been controversial since its discovery was announced last March. Its finders suggested the tablet showed writing in an early form of the Hebrew alphabet that called on the god of the Israelites to curse his enemies. But the new studies reject claims that the tablet is the earliest-known inscription of the name Yahweh and that it supports biblical accounts of the origins of the ancient Israelites.

"Maybe there’s something there," archaeologist Aren Maeir of Israel’s Bar-Ilan University told Live Science. "But with what they’ve published, there isn't."

Maeir is the lead author of one of the latest studies, and the editor of the Israel Exploration Journal that will publish three new studies addressing the tablet this week.

His own study examines the account of the inscription on the tablet described in an article published in May in the journal Heritage Science.

Maeir noted that only X-ray tomography images of the inscription on the inside of the folded lead tablet were given in the research article; but his examinations of them have revealed no inscriptions in any language. Instead, what appear to be letters are probably just indentations caused by weathering, he said.

"It could be that there are other photos, and that the outside inscription is in fact there," he said. "But from what we know, based on what has been published so far, there are many, many problems with their interpretation."

However, the tablet's finders told Live Science that there's more to be published about the object and that they’ll address the latest objections in future research.

The lead author of the Heritage Science article, archaeologist Scott Stripling of the U.S.-based Associates for Biblical Research (ABR), told Live Science that the original research paper was too long to be published in its entirety, and so it was split into two; a second article featuring the outer inscription would be published later.

Controversial claims

The Mount Ebal tablet was found in 2019 amid material excavated in the 1980s from the "Joshua’s Altar" site on Mount Ebal, just north of the city of Nablus in the West Bank.

Some archaeologists think the structure is where Joshua — who succeeded Moses as leader of the Israelites — sacrificed animals to Yahweh more than 3200 years ago.

But others think it is a sacrificial altar from the Iron Age, several hundred years later.

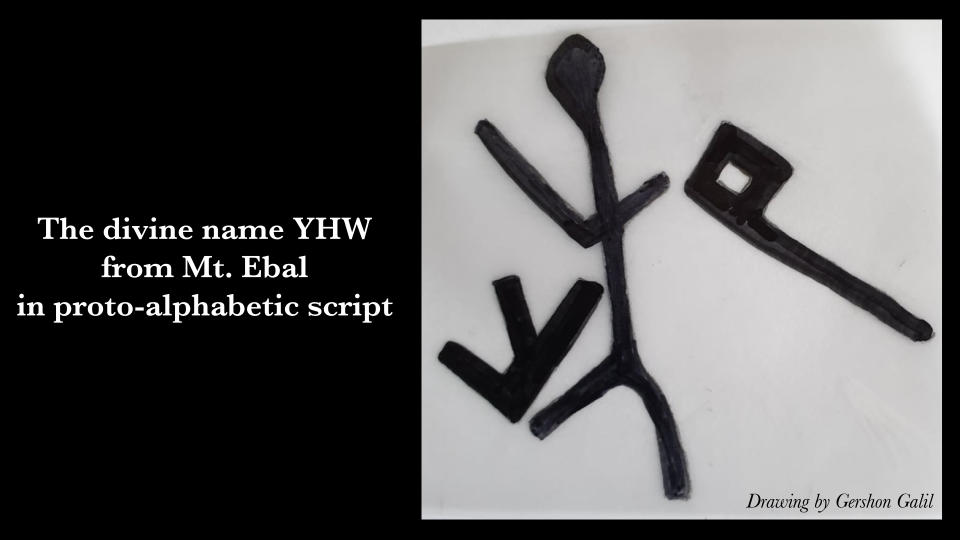

Stripling told Live Science in 2022 that the tablet was found in layers of earth that suggested it dated from between 1400 and 1200 B.C; and that the outer inscription contained proto-alphabetic” letters corresponding to the modern Hebrew letters yud, heh and vav, meaning Yahweh— the name of the Israelite god.

If so, the tablet would be the earliest-known inscription of the name Yahweh.

The finders also claimed that other parts of the inscription may be a "curse" calling for Yahweh’s intervention.

The inscription and the location match a view of history described in Deuteronomy, in which Moses commanded one group of Israelites to proclaim curses on Mount Ebal while another group proclaimed blessings on nearby Mount Gerizim.

Latest research

As well as rejecting the finders' interpretation of an inscription on the inside of the tablet, the latest studies also cast doubt on its age, its metallurgical origins and its purpose.

Maeir said that the object was found in spoil from an earlier excavation and so was devoid of any archaeological context.

A second study, by Naama Yahalom-Mack, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, confirmed the lead for the weight was mined in Attica in modern Greece, but couldn't determine when it was mined.

A third study, by archaeologist Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, suggests the tablet closely resembled a weight for the fishing nets common at the time; and although Mount Ebal is relatively far from the sea, it could have been used for fishing in nearby fresh water.

Maeir noted that similar nets were also used for catching birds and may have been similarly weighted for that purpose.

RELATED STORIES

—Blood-red walls of Roman amphitheater unearthed near 'Armageddon' in Israel

When contacted by Live Science, Stripling suggested the latest claims would be taken into account by the original researchers; but he added that critics of the Mount Ebal tablet sometimes seemed to be refuting statements that had never been made by the finders, such as that the lead's origin in Greece had determined its age, he said.

He and his colleagues expect to address the objections in forthcoming studies, he said.

"I am confident that there is writing on the tablet," he said. "It is natural for other scholars to reach divergent views, and I look forward to reading the forthcoming articles in the [Israel Exploration Journal]."