Curious What People Think of You? These People Invented a Brutal Way to Find Out.

A few years ago, Olivia McManus decided to run an experiment. The 34-year-old Vancouver Island native, then in her late 20s, was wrestling with a common social hangup: She didn’t know what people thought of her.

A couple of clues led her to worry. First, she was pursuing improv comedy, which relied on the connection between herself and the audience. But during sets, Olivia often noticed that some of the laughs she got were unintentional. She worried she was missing something.

Olivia brought this up to her therapist, who confirmed her suspicion that her self-perception might be off. When Olivia used words like “loud” and “bubbly” to describe herself in a session, her therapist gently pushed back.

“She was like, ‘I hear you say these kinds of things, but I don’t get that impression from you at all,” Olivia recalled. “So either you’re super different with me or there’s a disconnect.’ ”

Olivia needed more data. She had turned to elaborate color-coded spreadsheets and ranked lists to tackle things like vacation planning and baby naming before, so she decided to craft a survey that would ask for input about her personality. Determined to narrow the gap between how she saw herself and how others saw her, she sent the form to a trusted group of around 30 friends and family members. The survey asked respondents to describe their first impressions of her, and to characterize her voice, tone, and body language. It concluded with a question about how she could “best show affection” to those responding.

The results were surprising. A handful of people wrote she was “reserved,” and others described her body language as “guarded” or “avoidant.” One particularly memorable response pronounced her as tense, and “coiled like a snake.” “That was the one that I think about the most,” Olivia said. “I was like, ‘OK, I’m listening.’ ”

Olivia was shocked by the consensus among her respondents’ answers. For years, she’d tried to tone down what she worried was an over-the-top personality, but the experiment made her realize she’d been overcorrecting. “I was going in the wrong direction,” she said. Finally, she could see herself clearly.

Not everyone can handle such direct, dispassionate feedback. Intentionally inviting criticism—or coming to terms with the fact that others notice you at all—is famously uncomfortable. Back in 2020, it was common to see posts begging not to be perceived, and before that, the phrase “the mortifying ordeal of being known,” which was pulled from a 2013 essay in the New York Times, gained some notoriety. Olivia’s request for her friends and family to honestly describe her was a way to meet that ordeal head-on. And although the brutally honest feedback was unusual, she’s found aspects of it to be more helpful than in-person conversations with friends. After all, the feedback friends give each other is often softened to preserve the relationship and prevent the recipient from having a full-blown panic attack. This isn’t a bad thing, but if gentle feedback is the only kind you get, you might not get the full picture of how people actually perceive you.

That’s why one night, during a midnight study session in their sophomore year, two of my college friends wrote down and swapped lists of each other’s worst flaws.

Meher, 28, is one of the friends who was there. Their lists had a lot of overlap: They were both smokers, they drank a lot, and they weren’t studying as much as they should. “But we were good enough friends that [making the lists] wasn’t a mean thing to do,” she said. Being frank with each other felt like a testament to their closeness, and they ultimately decided that many of their “flaws” were worth keeping. Those traits made them who they are.

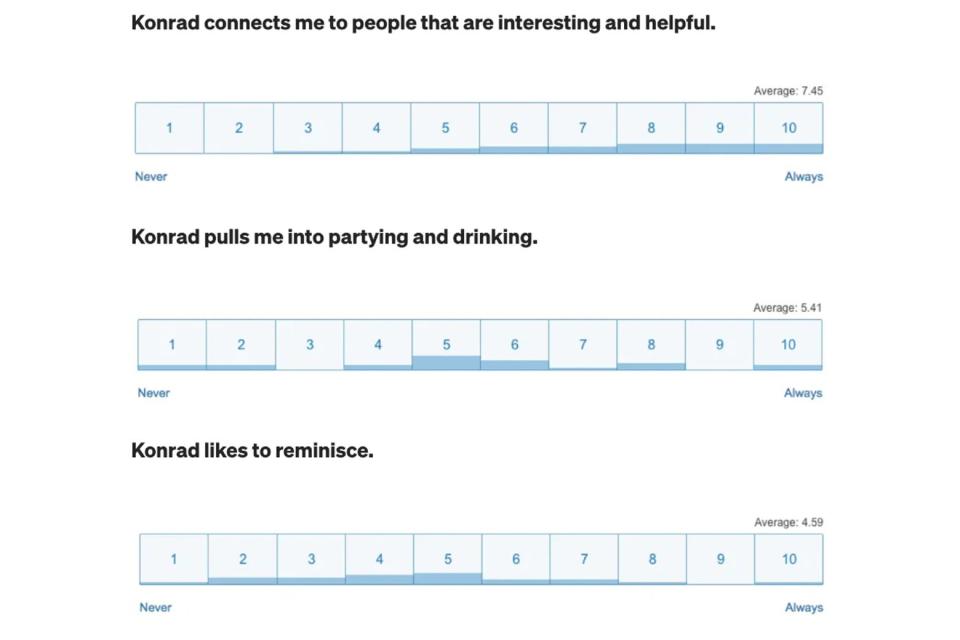

Some people crave a more structured version of this process. In 2017, Konrad Kopczynski, a marketing executive from New York, sent a survey like Olivia’s to 52 unsuspecting friends and acquaintances. “Random request, can you fill out a feedback survey about me as a person?” he asked in a message. “I’m curious how different my perception of myself is from others’ perception of me.”

Through the responses, Konrad found that others saw him as intelligent, interesting, and persistent. But he also learned that he could come off as arrogant, aloof, and cold. Someone said he was “stereotypically Upper East Side.”

He wrote about his feedback experiment in a Medium post that outlined the variables he asked about and how the responses made him feel. Though two people called him a “cyborg” and several people suggested he was both “unrealistic” and “likely to cause excess drunkenness,” he handled it with the cool removal of a scientist. After combing through the results, he concluded that he would “re-evaluate wardrobe to be less preppy” and “be friendlier to new people I meet.”

It’s not just data-minded individuals like Olivia and Konrad who do this, though. There are entire websites devoted to this kind of feedback, many of which employ their own proprietary method. Admonymous, a colleague-reviewing site started by two programmers in 2011, specializes in anonymous observations: People post their profile links on other social media platforms and invite friends to either “admire or admonish” them without their identities being known. Similar sites like Formspring—later rebranded to Spring.me—have been criticized for cyberbullying, but the Admonymous audience seems to be a bit more earnest and invested in self-improvement. As the profile of Yoni, one of the site’s founders, reads: “Yoni believes in keeping an open mind, but not so open that his brain falls out. Where is he going wrong without realizing it? He wants to know if he inadvertently hurts people around him, whether he really is as productive as he tries to be, and does he miss the truly important things in life while pursuing the wrong goals.”

Eloise Rosen, a 33-year-old software engineer who has maintained Admonymous since 2017, told me that many of the niche site’s early users were part of an extended network of friends who met through tech, rationalist, and effective altruist circles. Many of them connected through the controversial online forum LessWrong, where users discuss topics like philosophy, self-improvement, and futurism.

Eloise created her own Admonymous account back in 2013. Since then, she’s received more than 40 submissions. Most of them pointed out something she’d heard many times before: that she’s quiet and should talk more in conversation. Surprisingly, this wasn’t helpful. “Just getting a bunch of people saying I’m too quiet was kind of lame because I already knew about it and I’m trying to work on it already,” she told me. So, instead of taking the feedback she gets too seriously, Eloise said she picks and chooses which responses to take to heart. She finds the site’s anonymity useful, though: Compliments delivered in person can be written off as niceties, but anonymous feedback is more honest.

“If someone gives me positive feedback through Admonymous, there’s no social reason for them to do it,” she explained. “They’re not saying it so that I like them. They’re saying a nice thing because they think it’s true.”

But for some, anonymous comments from friends have been damaging, even when they’re invited. Joey Shelley, a 36-year-old user experience researcher in Boston, used Admonymous back in 2014 after finding the site through Facebook. Joey was already into online personality tests, so receiving anonymous feedback sounded exciting. But they were disappointed to get responses that ranged from unhelpful to hurtful.

Joey had recently come out as trans and received a number of anonymous comments that were transphobic. Those unexpected messages piled on stress during an already challenging time. “I thought it was just going to be fun and it would be nice if there was some constructive stuff I could work on,” they told me. “I didn’t expect something that I couldn’t do anything about.”

Still, they maintain a “profoundly morbid curiosity” when it comes to what others think of them. “Part of me is like, is it thick skin or is it just masochism?” they wondered.

Lately, Joey prefers to ask for constructive criticism from close friends and romantic partners. They have regular check-ins with their spouse, like on their anniversary, about how they could be a better partner. Konrad, the marketing executive, schedules similar quarterly “performance reviews” with his wife (so does this guy, apparently). But while Joey and their partner are “violently anti-capitalist” and avoid business language in their relationship, Konrad fully leans into it. In addition to his survey, he wrote a 30-page self-improvement document called “Evolution 2: 10x Your Mental and Physical Performance” that outlines his plan “to do more and be happier on a daily basis” and to “connect creative individuals with a helpful, effective structure like those found in a corporate setting.” The guide includes daily self-evaluations and devotional calendar use for important tasks like eating and sleeping.

Olivia also tends to professionalize her personal life. She keeps a spreadsheet of romantic interests, which helps her suss out patterns in her relationship behavior. A similar trend plays out on TikTok, where daters present their Dating Wrapped, compiling romance stats via slide deck at the end of each year.

For those who can’t resist the impulse toward personal data or brutally honest feedback from their friends and family, Olivia said she’d recommend her survey experiment. “A lot of people that I told were scared to send something like this to even their best friend,” she said. “But I loved it. I didn’t find it scary.”

She did offer one caveat, though: Come prepared with a thick skin.