Use Your Curiosity To Become A Better Climber

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Climbing

"Until I do it, it will stay on my mind...like an obsession." --Melissa Le Neve, on Action Directe (5.14d)

A route or boulder problem has you totally puzzled, bewildered. Nothing you try seems to work. The situation is frustrating and disappointing, and can even lead to doubting that the climb is possible for you. What do you do in this scenario? Perhaps you adopt a new training regimen or binge beta videos--or maybe you decide to move on.

We've all been there: We want to leave the frustration behind and send already. However, some of the best ways to improve performance involve not just physical training but rethinking your approach and mindset, in particular how you cultivate curiosity.

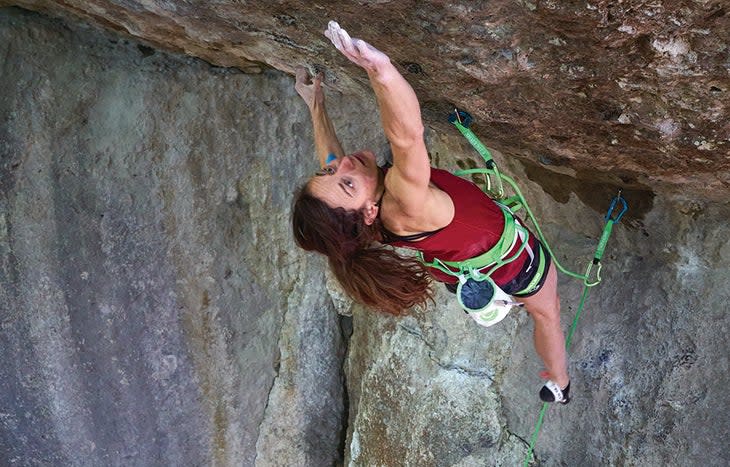

There's much to be learned from the longtime pro climber Melissa Le Neve (FRA) and her process. In May 2021, after a six-year battle, Le Neve sent Action Directe, the iconic 5.14d in the Frankenjura, Germany; hers was the first female ascent of the dynamic line, which climbs out a limestone swell on tiny pockets and was a turning point when put up by Wolfgang Gullich in 1991. "I will try every movement until I can do it. And not until I can do it, until I can do it in a smoother way," Le Neve says in an interview from her home in France. "Until I do it, it will stay on my mind...like an obsession." This is the mindset of curiosity, of earnestly seeking the best solution for you.

Recent research in the fields of movement science and psychology confirm that being curious and trying a variety of movement patterns and techniques help us to become better at our sport. Digging a little deeper into the science can teach us how to cultivate a successful performance mindset, to climb our hardest.

Complex Movements in Climbing

Climbing is filled with complex, infinitely variable movements, sequences, and types of multi-limb coordination, confirmed by watching different climbers try the same problem. One climber will match on a given hold, while another will span past it. One climber may throw a heel hook, while another hucks, utilizing momentum. The strategies we employ play to our individual strengths, often based on our unique physiologies. However, if we haven't built up a library of techniques to adapt to different routes, playing only to our strengths--our "chronic tendencies"--can become a weakness in and of itself. Curiosity, then, can help dismantle this tunnel vision and generate creative breakthroughs. In fact, many climbers experience the bliss of sending their long-term projects only after leaning into curiosity.

Let's go back to Le Neve and Action Directe (5.14d). Prior to her ascent, only men had climbed the route, and in similar ways to each other. Le Neve had to be extremely creative to unlock her own beta and even find her own advantages. At 5'7", she had more difficulty than previous ascentionists in tackling the infamous opening crux lunge to a tiny pocket, but it was a two-finger pocket for her, while a mono for the men. She learned to set up using a slight sideways hip movement, then jump hard to secure the pocket, shifting her center of mass quickly to the left for a powerful sideways reach. Every detail helped her to dial in her movement and training approach. Had Le Neve not unlocked her own beta by being curious--had she just continued to try the previous crowd-sourced, tall-guy sequence--the route might have remained elusive.

One approach to cultivating curiosity is never to believe that you have exhausted all possible options. Le Neve worked relentlessly for six years on Action Directe. She quit her competition career to focus on the route. When first stopped by the opening crux, she persisted. She kept an open mind, and she kept looking at the route from every possible angle, analyzing microscopic details. She experimented with ideas and tried anything that came to mind. She had a mindset that said, "There must be a way"--not, "There is no way."

Then, for a full year once she'd locked in her beta, Le Neve kept falling at the same place--a huge move to the left, three moves below the top. This kind of situation can be disheartening for anyone. She describes how she contended with it: "You shut down your mind. You try to be rational, taking [it] step by step," she says. "So you fall again--emotion doesn't help, so what do you do? What you can do is come back to, 'What did I do wrong?'"

Curiosity means you have to be willing to ask yourself difficult questions like this; you must also stay calm and persevere. When Le Neve was 3 years old, her father tried to teach her how to dig in the sand with a shovel, but she refused his help. She wanted to figure it out on her own. Likely this took longer--digging with her hands and using the shovel incorrectly, toddler-style--but she practiced persistent curiosity and discovery without additional assistance, building this habit even as a small child. How often do we climbers want to find a shortcut, to send quickly--say, by asking a friend for beta or watching YouTube videos? Neither is bad, but they can short-circuit the learning process. Think back to being in school: Would you learn more if someone did your homework for you or you worked through it on your own?

The Science Behind Movement Adaptability and Creativity

In movement science, frequently moving in different ways is called variability; it's defined as a lack of consistency or lack of a fixed pattern. For example, a sideways leg swing ("pogo move") may help in transferring the body's momentum in one specific context, while other contexts may require adaptability or slightly varied approaches (such as a slight rotation of the hip with a knee hike during the pogo move). Research in the fields of biomechanics and psychology relates adaptability to the balance between stability (persistent behaviors) and flexibility (variable behaviors).

Beginning climbers move in variable ways, as we learn new skills and movement patterns. The more curious a beginner climber can be from the get-go, the better. However, as we improve at climbing, we learn to use certain skills and movement patterns in stable ways. It becomes more automatic for us to determine what different climbs demand, and we may climb in less varied ways. This can both be beneficial and detrimental.

Now let's consider elite climbers--double-digits to 5.14-and-above. They typically create stable movement patterns over time, through experience and expanding their movement libraries. Moreover, they also retain the ability to subtly adapt their movements, carefully calibrating their sequencing according to performance conditions (e.g., routes and terrain, atmospheric conditions, their own level of fatigue, and so on). These subtle adaptations refer to a clever type of adaptability called neurobiological system degeneracy--a phenomenon that allows people to vary motor behaviors (types of movement and coordination patterns) without compromising function--that beginners do not have right away. This behavioral creativity lets elite climbers consistently adapt to the different routes and problems they encounter.

This world-class level of creativity can create paradigm shifts in sports. In World Cups, Janja Garnbret (SLO), who won the gold in at the Olympics in Tokyo, performs a signature move that's been coined the "Janja flick," arching her back into a Scorpion Pose-like position on dynamic moves. With the flick, Garnbret is able to actively adjust her rotational inertia by pulling more weight toward the center of her body, reducing the pendulum. She's not the only climber who performs the flick; other competition climbers such as Akiyo Noguchi do as well, and it's overall elevated the field. If you watched the Olympic bouldering event, you saw more examples of such adaptive curiosity and creativity at play. Before the climbing started, the competitors observed the boulders and strategized how to climb them, comparing beta solutions. When it was time to climb, if a movement pattern didn't work, the climber would think quickly--after all, they only get four minutes per problem--about how to move differently. Sometimes, they even completely changed their intended beta (e.g. Adam Ondra adapting his footwork beta on B2 which involved a coordination-style volume run-likely an anti-style of Ondra's). Even within the limited timeframe of the event, they were still cultivating curiosity.

For the average intermediate-level climber, it's likewise essential to incorporate behavioral creativity into our practice. As certain movement habits become automatic, chronic tendencies can develop, potentially forming strong connections in our brains that are hard to break. This is one way to plateau, when your movement capacity holds you back because you only move well in specific ways and contexts. Yet you can counter by learning a variety of techniques and movement patterns, and then applying them. Try many different types of climbs and styles: Try your anti-style. Try a variety of moves and keep trying. Ask yourself and others lots of questions. Lean into curiosity to break bad habits and develop your system degeneracy. As Le Neve puts it, we must "play with all the settings to arrive to that thing."

Five Drills to Challenge Curiosity

One of the best ways to promote curiosity in practice is to play games, ideally on climbs at your flash level or that are doable in a few attempts. These games/drills are best done on a bouldering wall or systems board. I'd recommend choosing one drill to incorporate as part of your warm-up. On days when you may want a lighter-intensity gym session, choose two to three drills and alternate through them for the session itself.

Drill No. 1: Limb subtraction

Climb without using one of your limbs (e.g., your right arm, which includes hand, forearm, and upper arm). Do the same problem and subtract a different limb each time. Notice how you have to adjust your movements and body positioning to compensate.

Drill No. 2: Hold elimination

Leave out a hold on a pre-set problem. The more critical the hold is, the harder the drill and the more creative you have to be. See how many holds you can eliminate and still send the problem. Notice how you constantly have to exercise your curiosity and creativity, as you may have to change your movement sequence and strategy each time.

Drill No. 3: One touch

In this drill, you are not allowed to make any adjustments on holds: Once you place your foot or hand on a hold, no repositioning. You must figure out the best body position and sequencing for the next move instantaneously, on the go. Notice also how precise and agile you have to be to secure each hold correctly. With practice, this process becomes more automatic.

Drill No. 4: Faster and faster

Climb a problem multiple times, timing yourself on each go. Try to climb faster every time--racing against yourself. Seek the best positions, and move as quickly and efficiently as possible. Notice how you can find your flow. You might also notice adaptability at work, as increasing your speed may force you to perform the sequences in slightly varied ways.

Drill No. 5: Static vs. dynamic

Some people describe themselves as mostly static or dynamic climbers. While it’s OK to have a preference, most routes and problems require a mix of the two styles. Try climbing a problem two ways: 1) only statically and 2) only dynamically. Climbing statically usually requires a focus on balance and slower movements, while climbing dynamically typically requires a focus on power and faster movements. Notice the subtleties in your positioning and movements as you find ways to force climbing in each style.

Thieves of curiosity

The three biggest things that can kill our curiosity are excuses, disbelief, and ego--if climbing is a mirror of your ego, then there is no place for learning and hard projecting. "You must have a strong belief with the open mind to learn. Then you're willing and able to try many things without worry," Melissa Le Neve says. Progress begins by letting go of your ego--becoming willing to fail--asking questions, observing, thinking, and analyzing. Even as you "fail," persevere, remember that your worth is not tied to how you climb. Inhale, exhale, and enjoy the process.

Invent your own games on the wall

As Tommy Caldwell put it in an interview about the Dawn Wall in the Denver Post, "As a climber…you want to find something that looks absurd and figure out how to do it." Climbing is an adventurous and playful sport. Inventing your own games is the perfect way to promote curiosity and learn new ways of coordinating your body. Make up rules that might seem ridiculous (e.g., every third move has to be a heel hook or double dyno). The more ridiculous the rules, the better. You could climb as if you are in a slow motion action scene in a movie. The more dramatic the moves are, the better. Or climb like how a dinosaur, robot, ballerina, or any other creature (real or imaginary) might climb. Don't use your thumbs, always hand-foot match, and so on. The possibilities for silly rules are endless. Then remember that for creating your own games, there are no rules.

Jasmin Honegger, PhD, is a climber, scientist, and a generally curious person interested in all things related to climbing science, human movement, and performance: @crimplabs, crimplabs.com.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.