A Cultural Critique of the Tesla Cybertruck

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

When people ask me why I’m an automotive journalist, I invariably give them one of two responses. The first—when I want them to leave me alone—is “I just always liked cars!” The second response, the real response, is that I actually wanted to be a cultural critic. Sadly, that’s not a real job anymore. Cars, in American society, are the next-closest thing to culture itself, and so I chose to focus on those.

While most days, I do focus on the “I just always liked cars” component of my job, sometimes a new vehicle comes along that provides such cutting insight into the country I live in that I have to drop everything and analyze it. This happened to me last week. From the perspective of a cultural critic, the Tesla Cybertruck might be the single most interesting vehicle of the twenty-first century.

Get Your Kicks (on Interstate 66)

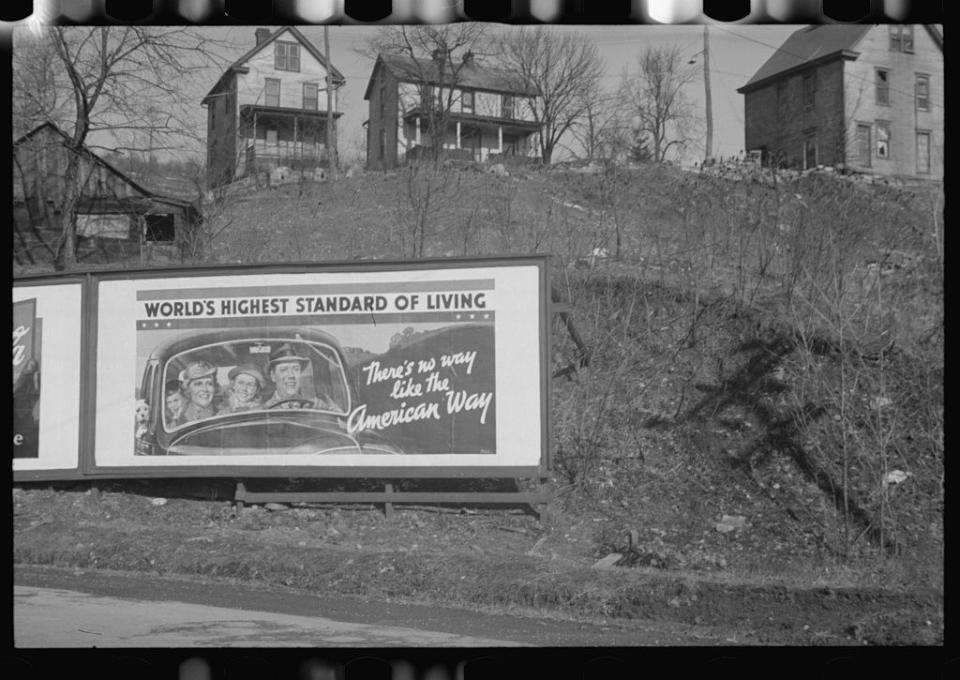

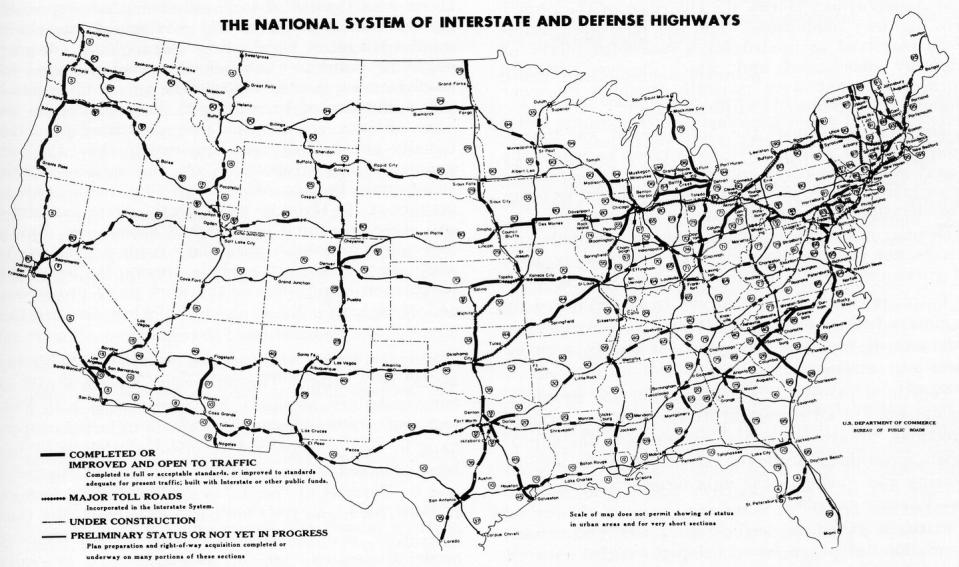

I will justify this claim, but first, I must give a brief history of America. Automobiles in the United States occupy a special place in our conscience. Our country’s transformation from an isolationist backwater to the industrial empire that dominated the twentieth century is inextricably linked with car culture. Not only did the automobile (and the Federal Highway Act of 1921) allow Americans to travel from coast to coast in a quick and safe manner at home, the mass-production techniques developed to build them at unimaginable rates were crucial to winning World War II, beginning decades of American dominance. In parallel with the automobile and because of the automobile, the American West became heavily populated and the United States cemented itself as the primary superpower of the global West. The America everyone alive today has known and lived in was built on the back of “a car in every garage”.

Post-World-War-II, when Eisenhower declared that America would build the Interstate Highway System for national security purposes—and therefore, federal funds would always support an auto-centric society—he cemented that American culture would simply be car culture for as long as the United States and the automobile existed. Car ownership among Americans doubled in the decade after WWII; by the end of the Fifties, one in six Americans were employed (directly or indirectly) by the auto industry. As this shift occurred, the automobile’s design transformed from a relatively utilitarian two-box design to a highly stylized reflection of the culture surrounding it.

But none of this should be news. Car enthusiasts inherently know that the postwar optimism of the Fifties is practically synonymous with the ever-growing height of land-barge tail fins, and the blocky restraint of Sixties sedans got ever-more-serious, virtually beat-for-beat, as the country grappled with waves of assassinations and social unrest. The uncertainty of the Seventies brought with it the awkward styling of an industry caught off-guard; the Eighties saw the rise of tech-centered Japanese futurism and its aero-forward wedge styling take over American roads.

Cars are unique in their cultural accuracy, too. Architecture moves at a glacial pace (Googie architecture lasted 25 years!) and fashion is ultra-rapid (Dior’s New Look, one of the most influential trends in women’s clothing to ever exist, in its purest form lasted roughly four years), and both of those fields’ designs are vastly different for the wealthy and the average. Automobiles, on the other hand, update roughly every three to seven years, and there is a car for every price point and demographic imaginable, since almost every American needs one.

From all of these eras, certain models—from the exotic to the every day—seem to be perfect windows into our country’s ego and id; they show what it values, and what it fears, at the moment of its release. The ‘57 Chevy, with its vast expanses of gleaming chrome—and its ads full of perfectly-trad-beautiful gleaming white smiles and white faces—became shorthand for the rock n’ roll Fifties; the stainless-steel Delorean DMC-12 and the unreliability underneath its gleaming sci-fi exterior came to represent the hollow futurism of the Reagan Eighties.

Which neatly brings us to the Tesla Cybertruck and the fraught present.

We Didn’t Start The Fire

Hindsight makes most of these observations about bygone models seem common sense, but it is of course much harder to accurately describe a historical moment as you live through it. It would ordinarily be even more difficult to choose something to represent that moment.

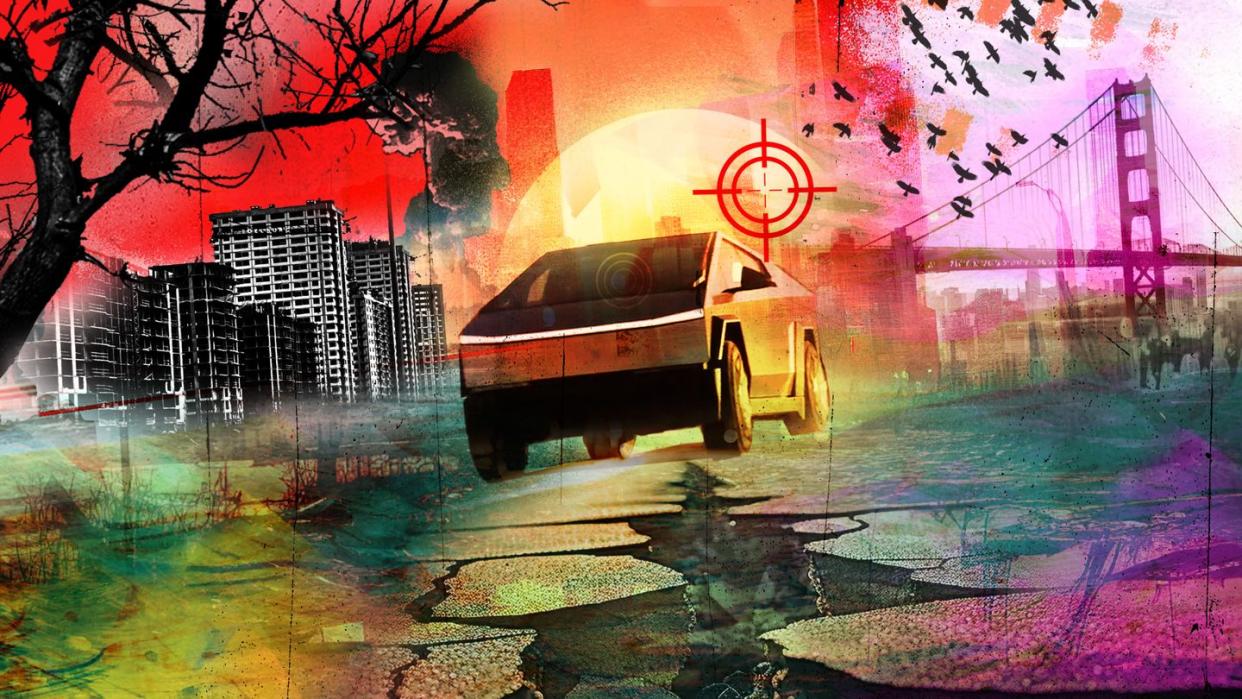

Luckily for us, the Cybertruck and Tesla CEO Elon Musk are not subtle about their aims. Stylistically, of course, the Cybertruck looks like a parody of an Eighties dystopian future. More Total Recall’s Johnnycab than Blade Runner’s Peugeot Spinner, although that has not stopped Musk from making parallels to the latter film. He, after all, announced the Cybertruck in 2019 on the same day the original Blade Runner film is set. That launch event four years ago featured Musk harping on the rugged nature of Tesla’s new pickup, throwing steel balls at the impact-resistant windows and mentioning that the stainless-steel skin of the Cybertruck would be “literally bulletproof to a nine-millimeter handgun.”

In the four years since the initial announcement of the Cybertruck and its release, Musk has doubled down on these comments. He has called the Cybertruck “what Bladerunner would have driven” and “the finest in apocalypse technology”. Press videos released by Tesla show entire MP5 magazines emptied into the doors to drive home the body's bulletproof nature. Musk’s emphasis that the Cybertruck is an “armored personnel carrier from the future” is likely driven by his belief that “the apocalypse could come along at any moment.”

While Musk is, to say the least, well-known for outlandish statements, he does seem to genuinely believe society is on the precipice of a collapse. Over the past decade during his Tesla-fueled rise to prominence, he’s repeatedly expressed concerns that killer robots will threaten humanity in the near future and called artificial intelligence “our biggest existential threat.” His more recent embrace of right-wing rhetoric seems to have only deepened this belief; during a recent trip to the U.S.-Mexico border, he stated that undocumented immigrants will cause “a collapse in social services,” and he believes that falling birthrates—caused, in his view, by birth control and abortion—are a “much bigger risk to civilization than global warming.”

It Starts With An Earthquake, Birds and Snakes

Whether Musk truly believes society is near collapse—or if it is truly about to collapse—are immaterial. What is true is that a majority of people—across virtually all demographics and ages—agree life in America is getting worse, and we must steel ourselves for the grim future ahead. More Americans are pessimistic about the future of the country than optimistic. Almost three-quarters of Americans believe, at least somewhat, that “the country is falling apart.” This is reflected much closer to home, as well; polling shows that a quarter of Americans fear being attacked in their own neighborhood.

And our vehicles reflect these anxieties. More than half of vehicles sold today in America are trucks and SUVs; this fueled a new all-time high for the average weight of a new passenger vehicle in 2022, which hit a staggering 4329 pounds. Pickup buyers, more frequently than other types of vehicle owners, say they enjoy their trucks because they are “powerful” and “rugged”. Most new vehicle buyers rate vehicle safety as a top priority in their purchases, and larger vehicles are indeed safer for occupants than small ones (although they have vastly more negative externalities, such as tire particulates and dead pedestrians).

So automakers have given us what we demanded, and the stylistic language has changed to match: the overarching trends of this decade thus far is to make our vehicles broader, heavier, boxier, and more militaristic in nature, as rounded lines don’t project power. The Cybertruck—which Musk stated at its launch “will win” in an “argument” with other vehicles—simply follows all of these themes to their logical endpoints.

A bulletproof three-and-a-half ton stainless-steel truck equipped with “Bioweapon Defense Mode” designed to slam through other cars is the perfect vehicle for a society where over a third of people are scared to walk around at night.

I’m Afraid Of Americans

I moved recently from a rural town in Idaho to the heart of Seattle, a change I’d been longing to make for ages. When I told my mother I was finally relocating, she told me to avoid walking outside in my neighborhood, because she had heard it was dangerous. She has not been west of the Mississippi River at any point in my entire life. She is simply an avid Fox News watcher.

The Cybertruck is the perfect vehicle for her. It is the perfect vehicle for a culture where everyone is afraid of their neighbor. Musk’s bulletproof wedge-shaped machine is the physical manifestation of America’s fear, and whether it is good or bad, we deserve it.

You Might Also Like