The Crucible: the play that warned us about ‘cancel culture’

It was just a pointed allusion in a passing tweet, but this week J K Rowling set squarely in the public domain what has been in many people’s minds for some time.

“You’re still following me, Jennifer,” the author wrote on Wednesday, addressing fellow author (and one of her 14.3 million Twitter followers) Jennifer Finney Boylan, after the latter apologised for having signed an instantly controversial open letter (to be published in Harper’s Magazine), along with more than 150 other authors, attacking a liberty-curbing climate of intolerance, censoriousness, shaming and ostracism – so-called “cancel culture”.

“Be sure to publicly repent of your association with Goody Rowling before unfollowing and volunteer to operate the ducking stool next time, as penance,” the creator of Harry Potter jibed – an explicit reference to the Salem witch trials of 1692.

What happened in Salem constituted the deadliest witch hunt in American history. For a year, this God-fearing, Puritan-minded town in colonial New England succumbed to hysteria and havoc. Multiple accusations of witchery, detected in its citizens on negligible evidence, with suddenly empowered girls leading the denunciations, resulted in the merciless application of the law.

More than 200 were accused; 30 were found guilty, of whom 19 went to the gallows, the majority women. The court records confirm the use of “Goody” – a shortened version of Goodwife – to refer to the accused. When news broke that Elizabeth Proctor, who survived but whose husband John was hanged, was to be summoned for questioning, one accuser reportedly shouted: “There’s Goody Proctor! Old Witch! I’ll have her hung.”

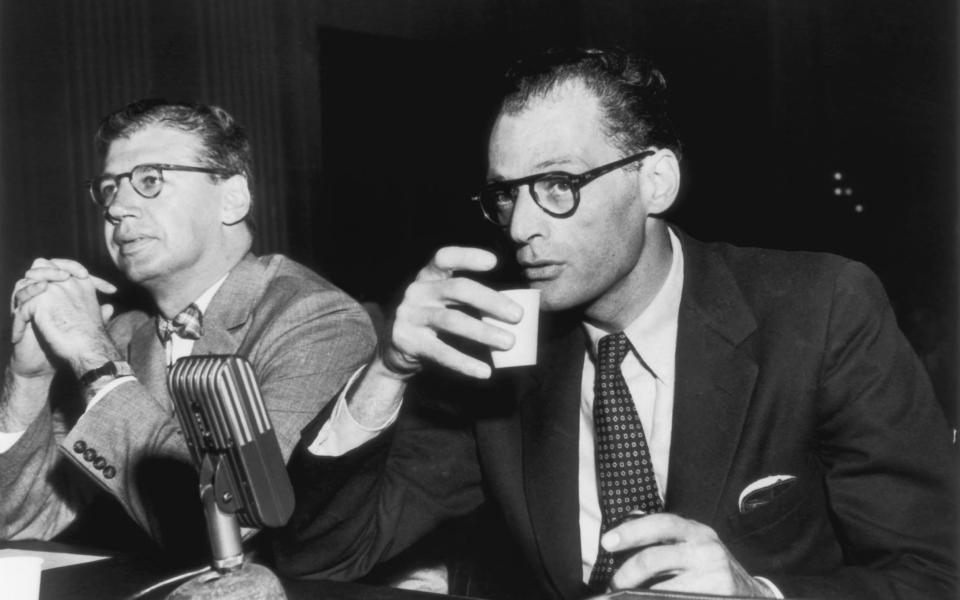

It was Arthur Miller who made what happened in that suddenly benighted corner of Massachusetts a renewed cause célèbre with his 1953 play The Crucible. Miller conjured the past with poetic licence but much commendable fidelity, too. The object of the exercise, though, was to create an allegorical parallel. He had in his sights the mania for the denunciation, blacklisting and purging of Communists, former Communists and suspected Communists, in what became known as the McCarthy era (after the most zealous pursuer of this supposed fifth column, Republican senator Joseph McCarthy).

In Miller’s eyes, the political establishment had slipped its moorings with reality – and morality – bearing down on individuals for their perceived intellectual wrongdoing, most notably in the case of Elia Kazan, who had directed Death of a Salesman and who buckled under pressure, naming names before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), in 1952, thereby causing a rift with Miller.

For Rowling, the parallels between Salem, McCarthyism and today are clear. On Twitter she has also quoted the playwright Lillian Hellman’s remark, “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions”, made in a letter to HUAC in 1952.

We’re barely more than halfway through the year, the theatres have been closed for half that time and uncertainty remains as to whether we’ll see any activity in many for the remainder. Even before Rowling’s pronouncement, though, I’d have suggested that things have taken such an ominous turn that Miller’s canonical work feels like the most urgent, vital play of 2020.

In 1996, on the release of the film version starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Winona Ryder (directed by Nicholas Hytner), Miller suggested that The Crucible could be applicable “to almost any time… I wrote it blind to the world. The enemy is within, and stays within. It’s always on the edge of our minds that behind what we see is a nefarious plot.’’

In his biography of Miller, Christopher Bigsby outlined the correspondence between the Puritan “terror” and the Red Scare. Back then, “The accuser was innocent, the accused assumed to be guilty and stripped of social power. Judicial processes were perverted, a new language deployed. Survival depended on submission and an acceptance of the paranoid vision… the casting-out of devils was seen as a national responsibility, the penitent an image of reborn man.” Sound familiar?

Aside from the torrent of complaints – and more – directed at J K Rowling for her views on trans issues, the past few months have offered the repeated spectacle of people being dragged into the court of progressivist public opinion and denounced – their only hope of rehabilitation to recant and “work harder” for acceptance.

The modern penalty for failing to move with the herd when it’s charging in one direction, or for being identified as antithetical to it, may not be as grave as swinging from the gallows. But as Douglas Murray, author of The Madness of Crowds – the bestselling critique of the rampancy (and tyranny) of groupthink in the age of identity politics – recently noted, “The stakes are quite high for most people”. Failure to comply with the avowed Left-liberal agenda (the opposite, but still analogous, situation to Fifties America) carries life-changing risks – the loss of work, demonisation.

To take one example this week, the sudden, furious attempt on social media to “cancel” Jodie Comer, the Killing Eve actress. The grounds? It was concluded, on the slenderest online evidence, that she was dating a Bostonian lacrosse player, James Burke, who was deduced to have voted Republican. That was enough to get #JodieComerIsOverParty “trending” on Twitter.

Re-watching Yaël Farber’s shiver-making production of The Crucible at the Old Vic in 2014, you get a visceral physical correlative to what might nowadays find expression as an online mob, as the girls of Salem twitch, convulse and finger-point as if surrendering to supernatural powers that carry the force of irresistible truth. Miller allows us to sit at one safe historical remove from the scene, but the “theatre” of it draws us in, implicates us in mass credulity.

He identified the private impulse behind the public act, the factionalism, self-interest and instability to which the majority of us are prone – detecting in the town’s runaway unreason the unleashing of repressed sexual urges. This finds its most pivotal expression in the figure of Abigail Williams, who incriminates Elizabeth Proctor because she hankers after the latter’s errant husband John, the play’s hero.

Proctor goes to his death having been offered the chance to live through accepting his guilt and naming others: “I speak my own sins, I cannot judge another. I have no tongue for it.” In a remarkable case of life mirroring an author’s own art, when Miller was subpoenaed before the HUAC in Washington in 1956, he refused to name names, declaring: “I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him.”

He was charged with contempt, appealed and eventually won. The McCarthyist frenzy abated. He was vindicated in his opinion towards Kazan, as recorded in his memoir Timebends: “I could only say that I thought this would pass and that it had to pass because it would devour the glue that kept the country together if left to its own unobstructed course.”

Those fearing the worst ramifications of today’s culture wars can take some comfort from the fortitude, and wit that got Miller through that period (expressed through Proctor’s own dry eloquence: “This society will not be a bag to swing around your head,” he tells one adversary). But The Crucible still offers a timely, chilling warning from history that something deep, disturbing and very possibly ineradicable in our nature likes to march in step, crushing dissent, heedless of the destination.

Watch the Old Vic production of The Crucible at digitaltheatre.com