Critic A.O. Scott Reveals the Films He’d Happily Live In

Above: A seaside house near Rome is the setting for a decadent party in La Dolce Vita.

If you asked me to name my favorite movie, the answer would be La Dolce Vita, Federico Fellini’s sprawling 1960 spectacle of modern Roman decadence. If you asked me why, I’d say that, more than any other film I can think of, this is the one I wish I could live in.

Which, I admit, is a bit perverse. The people in this movie are glamorous and good-looking—Marcello Mastroianni in his slim suits and sunglasses; Anouk Aimée in her black cocktail dress; Anita Ekberg with a kitten on her head—but also notoriously alienated and miserable. Don’t get me wrong—it’s not that I want to be like these people (as if I could). When I say I want to live in the movie, I mean it literally: I’m coveting the real estate.

That includes Rome’s famous public spaces, of course, like the Trevi Fountain, where Marcello and Anita take an impromptu, fully clothed, late-night dip; and the Via Veneto, where the stars strut and the paparazzi prowl. But the real magic of La Dolce Vita, its endlessly seductive art, lies in the interiors. There is the apartment of Marcello’s learned friend, Steiner, where artists and intellectuals gather for lofty talk in a spacious, book-lined salone. There is the villa in Ostia where Marcello, undone by Steiner’s death, hosts an all-night bacchanal that spills out onto the beach at dawn. And there are a series of more briefly visited palazzos and suites. I long to linger in all of them. However mean, messy, or fussy, every kitchen and bedroom in La Dolce Vita expresses a coherent aesthetic. Really, they are testaments to the genius of Piero Gherardi, the production and costume designer, who is one of the unsung heroes of Italian cinema. “He’s like a diviner, out to find the physical version of something you think you made up,” Fellini once said of his friend and frequent collaborator.

Or, to put it another way, Gherardi—who was nominated for six Oscars, winning two, for the costumes in La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2 —was able to imagine the shape that reality was taking. Postwar Italy underwent a dizzying series of economic, cultural, and demographic changes. A mostly rural society urbanized rapidly; southern agricultural workers migrated to the industrial cities of the north; women gained access to the workplace and the voting booth; new gadgets and products could be purchased, or at least desired, by members of every class.

Gherardi, trained as an architect, captured the way this revolution remade domestic spaces. The Italian home is where novelty collides with tradition, where family photographs and pictures of saints hang alongside movie posters and pinups, where rituals of table and hearth persist in the presence of kitchen appliances and television sets. Gherardi saw the comedy and the pathos inherent in these collisions.

Before La Dolce Vita he and Fellini worked together on Nights of Cabiria, the episodic tale of a Roman prostitute (played by the director’s wife, Giulietta Masina) that is also a showcase of midcentury Italian vernacular architecture and design. Cabiria likes to boast that she owns her own house, a boxy, one-room cement-block bunker (designed by Gherardi) on the desolate margins of Rome. The decor is as warm and idiosyncratic as Cabiria herself—a curated array of keepsakes and useful objects. Later, she spends an awkward night in the opulent home of a movie star, marveling at the furniture, oversize aquariums, and massive closets. Neither she nor her host can be accused of having good taste. That may be an irrelevant concept in the world of Fellini, who was as fascinated by vulgarity as he was by elegance.

In Big Deal on Madonna Street, Mario Monicelli’s farcical 1958 heist picture, we meet the members of a ragtag gang of would-be jewel thieves partly by seeing where they live. Though the rooming houses and cramped apartments are nondescript, the interiors are full of specific life. That includes the kitchen where the movie reaches its climax. The burglars wind up there by mistake after drilling through the wrong wall. Having missed out on a safe full of treasure, they settle for a pot of leftover pasta e ceci—a metaphor, perhaps, for the kind of satisfaction that money can’t buy.

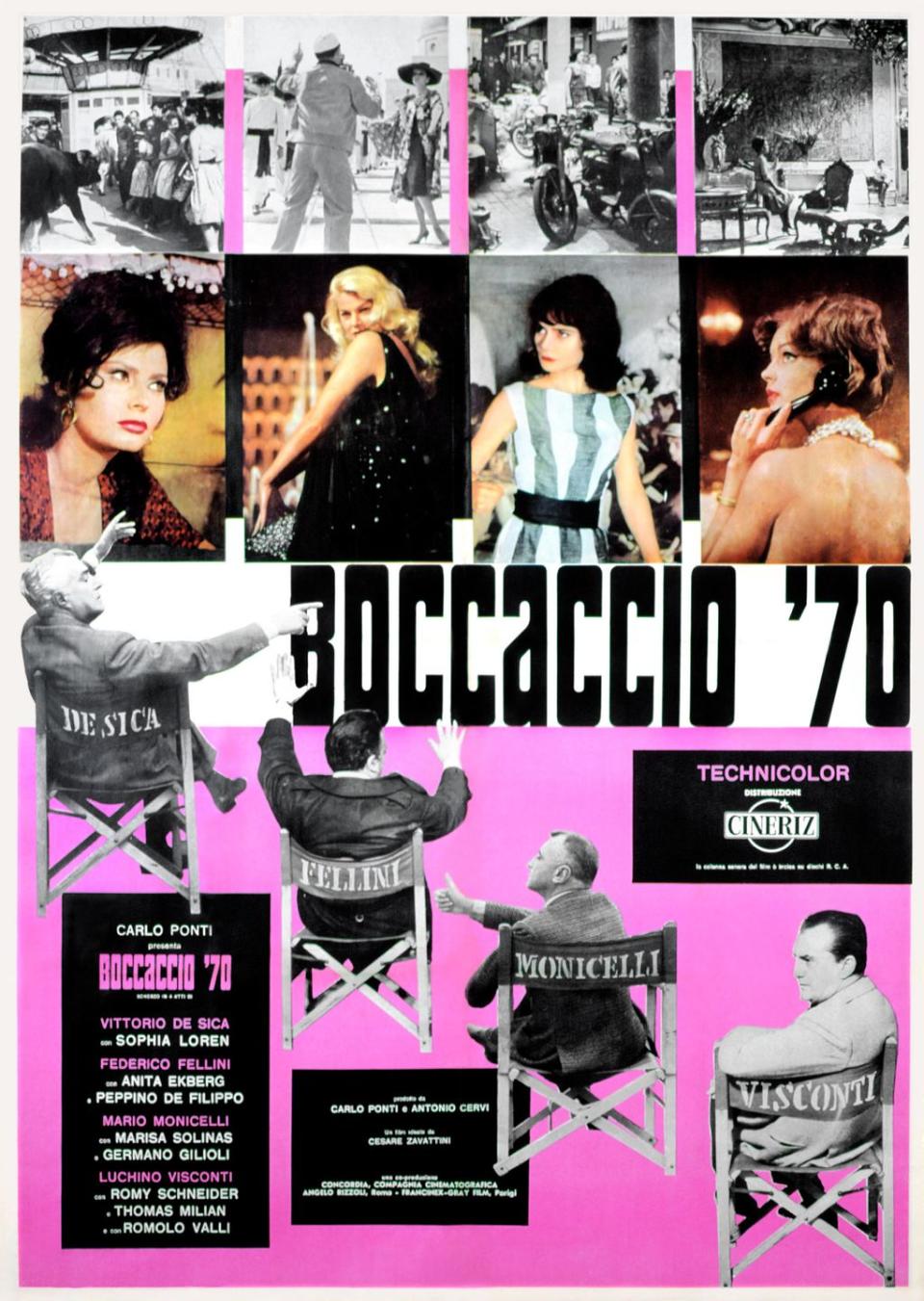

The young couple in Monicelli’s “Renzo and Luciana”—a chapter in the all-star auteurist anthology film Boccaccio ’70—yearn for a different kind of satisfaction. Newly married, they live in a gleaming, modern Milan apartment with Luciana’s extended family. The thin, white walls make privacy impossible, and their untapped lust becomes the engine of upward mobility. The couple work extra shifts and find a cozy one-bedroom of their own, feathering their nest with mass-produced, store-bought commodities—lamps, cups and saucers, a nice big bed—that are magically infused with their own sensual, optimistic, striving sensibilities.

Though I’d hesitate to intrude on Renzo and Luciana, I’d happily inhabit that movie, too, or just about any other Italian movie from that era. I’ve been watching a lot of them over the past year, in the tedium and comfort of my own home. It’s an odd form of escapism, traveling through time and space into imaginary worlds that seem so perfectly—so crazily, passionately, creatively—lived in.

A.O. Scott is a chief film critic at the New York Times.

You Might Also Like