Dear God, Why Do You Keep Trying To Kill Me?

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Dear God, Well, once again you've tried your hardest to kill me, and it hasn't worked. This last time--a head-on with a truck while I was on a motor scooter on Caicos in the Caribbean--was a doozy. I also thought the plane crash in Stehekin or the kayaking calamity on the Salmon River years ago might really be the end of it all, but those, too, proved insufficient.

This pursuit of yours has been going on a long time, spread over 60 years and a couple dozen activities, frequently in the mountains. I know you're fond of Moses and his trip up the Mount. Is that why you chose me?

It began in 1977 with that fast one you tried to pull on Denali. Descending from the summit, I stopped on the edge of the bergschrund to take a break and watch the rest of the crew descend to camp at 14,000 feet. As I stood admiring the view and basking in the great glory of our ascent, whump--the edge broke off. Oh, you almost had me there, but I fooled you: I was tied to a fixed rope.

That must have pissed you off, because next thing I knew I was hanging upside-down in the yawning blue-ice crevasse, strapped to a 70-pound pack that completely cut off my air. Breathing at 14,000 is hard enough (I'm not sure what it's like up in Heaven), let alone with 70 pounds of dead weight crushing your chest. As I hung in midair thinking about what I was going to say to you when we met, I realized I had one small chance to delay the conversation.

Frantically yanking at the buckles, I was able to release my pack straps, and slowly lower the pack with one outstretched arm until it was poised above a foot-wide shelf. Just as I was about to pass out, the blood pounding until my eyeballs hurt, I dropped the pack, and--I'll give you this one, God--it miraculously landed with a thump and stayed on that little ledge. I was just able to touch one foot onto the pack, unweight the ascender, and release myself.

I slid onto the pack and sat for a long time, sucking in oxygen and contemplating my next move. I clipped back into the rope, jumared up to the lip of the crevasse, and stumbled down to camp.

I guess you were just getting started. The next summer while my friend Mark and I were climbing El Capitan, the 18-inch ledge we were sleeping on collapsed, sliding away at 2 a.m. in a tremendous nighttime display of thunder and sparks and ozone. Too bad for you--we had tied into a couple of bolts above the ledge. We were simply left hanging in space wondering what the HELL (sorry to bring that place up, God) had just happened! We spent the rest of the night suspended like frightened bats, dreading any further tricks you had up your sleeve.

One of your very best attempts, of course, occurred the following winter while I was driving over Washington Pass, which links western Washington to the eastern side of the Cascade Mountains. It was snowing hard as I headed east from Seattle. Arriving at the west-side highway gate--usually closed during dangerous storms--I found it wide open, so I continued, happy not to have to take the six-hour detour to get home. Naturally, you had arranged for the highway workers to close the gate just a few minutes after I went through--and, in a fit of divine inspiration, had them call the gatekeepers on the other side saying there was no one on the road, so to close their gate as well.

As you know, God, because you designed the pass, a dozen major avalanche chutes above the road deliver massive slides during a storm. These slides start way up in the steep, narrow gullies between the peaks, and hit the highway carrying enough snow to bury a small town. At 200 mph.

So here I was crawling along through the storm in my two-wheel-drive van in the dark, trying to make out the completely snow-covered road, mostly from memory. I crested Washington Pass and hooted in delight. I made it! Home in half an hour. It's all downhill from here.

It certainly was. As I peered through the iced-up windshield, the wipers trying in vain to keep a small patch clear, my van lifted up and spun around. It was a very strange sensation, since I had no visibility or point of reference. I could feel my body shift forward, then to the left, then forward again, with no noise or sense of direction. A few seconds later the movement stopped, and so did the van. It was totally dark, though my headlights were still on. I sat there for a minute trying to make sense of what had happened.

I tried to open the door. Nothing. I turned on the inside light and looked around. Snow was packed tight against all the windows. I put on my gloves and hat, zipped my jacket tight, and rolled down the passenger side window. The snow was rock hard. Only by drooling (on purpose--please) did I figure out that up was actually toward the back of the van. I started digging through the window, using a small shovel I always carried, thank God (you).

An hour later I had tunneled perhaps eight feet but still had no idea how deep I was buried. Ten minutes later I finally punched through. By this time not much oxygen was left in the van (or me), and I eagerly sucked in the cold, snowy air. The blizzard was still raging as I wormed out. I tried to figure out where I was by using my flashlight but it only penetrated a few feet into the thick darkness.

Suddenly I saw another light, flashing yellow far below me. It came and went as gusts of wind blew the billowing snow into my eyes. Then a flashlight beam appeared, swiping back and forth, occasionally hitting me. I waved and yelled into the storm, unsure of how far away the light was or what anyone was doing there.

Not knowing whether I would ever see my van again, I crawled and waded through two feet of snow for almost an hour before reaching two highway workers, camped in their truck at the bottom of the pass. They had seen my headlights snaking around the pass, then suddenly tumbling and shining all over the place--and disappearing.

We all piled into their truck, and they gave me a ride home. During that drive I believe your name and your son's name came up several times.

The following summer I think you meant it, though. Perhaps over the rest of that winter you had been stewing on my name-calling.

The forecast for Mt. Rainier called for sunny and warm weather, clear skies and crisp nights for a week: ideal for a springtime ascent of the Liberty Ridge. I gathered up three friends and a pile of gear and drove to the end of the road on the northeast side of the mountain.

The weather was perfect during the long slog up the Carbon Glacier to base camp. The following morning we headed up early, hoping to make the summit in the afternoon, bivy on the other side, then circle back to base the next morning. Easy.

We moved fast and by 10 a.m. reached the base of the ridge. We put on crampons, grabbed our ice axes, and made good progress up the steep ridge. Seeing how much fun I was having, you decided to intervene, I guess. Around noon the sky clouded over, but we didn't really notice, since the forecast was for perfect weather for at least three more days.

By 2 p.m. it was snowing, and I did notice: Hey, now, what's this? By 3 p.m. it was dumping hard, with four inches of thick, heavy snow blanketing the steep ice. By 4 there were eight inches, and we clearly weren't going to make the summit. Small avalanches started pouring down around us.

We were only 500 feet from the top of the ridge, and another hour to the summit, but in a total whiteout. We all took our ice axes and started chipping out a couple of small caves in the rock-hard ice. Two hours later I had a hole large enough to crawl in and barely sit up, with my feet dangling over the edge.

Yes, God, I sat and shivered for three days in that cave while you let loose with the monster storm that had all the weather forecasters scratching their heads. We quickly ran out of fuel for our stove, so had no hot food or means to melt snow for water. I chewed on a frozen piece of beef jerky for two days.

That was quite a sucker punch you threw on day three when the sky cleared slightly, and I crawled out of my hole and tried to claw upward in three feet of new snow. I made 100 feet in an hour before realizing the futility of the effort. When you sent that massive avalanche down the Willis Wall just a hundred feet to my left, you were offering a clue: to wait another day, even with no feeling in my fingers or toes. You must have had enough fun with me for the moment.

By day four everyone was hypothermic, and one member of our group wasn't going anywhere, up or down. Time to bust a move. We bundled the guy in our sleeping bags, told him we'd be back (maybe) with a rescue, and started down the ridge.

Avalanches crashed down all around us, and it was only by your grace that we weren't swept away. I left two of my mates at base camp and ran out to the ranger station eight miles away. On my frozen feet.

It all ended well since you blew the storm away and let that helicopter go rescue everyone. And by the way, thanks for not having that doctor amputate my toes.

Of course who (not me) could forget getting struck by lightning?

I was running a small guide service in Mazama, Washington, when I got a call from the District Ranger at the Forest Service office asking if I knew anything about a climbing accident on Liberty Bell Mountain, 20 miles up the road. I phoned around and learned that a leader had fallen high on the spire, shattered his leg, and was apparently still up there. The rest of his crew (friends?) had left him up on the mountain and driven home, but at least stopped to alert the county sheriff. Unfortunately they couldn't describe exactly where on the mountain it was, and couldn't show anyone because they had to get home to go to a party that evening.

The borders of three different counties intersect on the summit of Liberty Bell, which was pretty clever of you, God. This means that three different County Sheriff's Departments get to fight over who is in charge. Sometimes they all want to be in charge (good press coverage) and other times none of them want anything to do with it (no press, tight budgets).

The District Ranger asked if I would assist in a rescue, so I called one of my guides, Dave, to help. By this time it was 9 p.m. The victim had been up on the mountain since 8 a.m. Dave and I hiked up to the base of the rock in the dark and bivied, awakening just before dawn to watch a long line of would-be rescuers meandering up the trail below us, their headlamps bobbing erratically in the dark.

Having been up this climb dozens of times, I had a good idea of where the accident had probably happened. Dave and I roped up and began the ascent. An hour later we found the victim, Larry. I think the only thing that saved him during his long, cold night on the mountain was the fact that he weighed about 250 pounds. How he even got that far up, I have no idea. I think you must have had something to do with that, God.

Larry had grabbed onto a notoriously loose off-route boulder that had been teetering on a ledge for a thousand years. It tumbled down, of course, and landed squarely on his right leg, shattering it and leaving a gaping wound with bone sticking out.

I got out my first-aid gear, which at the time was mostly several rolls of plaster gauze and a couple of water bottles. I wrapped up Larry's leg--pants and all--with the plaster and soaked it with water. Pretty soon it hardened, and he was just one big cast. I also gave him a shot of morphine, which put a big smile on his face. Far below us, the county "rescue" crew was scrambling around the base of the rock trying to figure out what to do next.

Since we were only 200 feet from the top, Dave and I decided that rather than lower the now 300-pound plastered-up Larry to the bottom and manhandle him two miles down rough trail, we'd haul him to the summit for a helicopter pickup. I used my walkie-talkie to call the sheriff, who was down in his truck eating doughnuts.

"We're taking him to the top," I told him. "Get a helicopter to meet us on the summit in two hours."

"A helicopter?" came the reply. "Oh, no, we can't do that. That's not in our budget. You'll have to bring him down."

"No, I won't," I responded. "If we try to do that he might die. Or at least lose his leg. You order that helicopter, now! There's a storm moving in. That chopper better be at the summit when we get there!"

Having guided on these peaks for 10 years, I was well aware that in the summer the afternoon storms roll in almost every day, with thunder, rain, sleet, hail and--yes, God--lightning, tearing at the solitary granite summits along the jagged ridges of the North Cascades.

Dave and I rigged a pulley system and began hoisting Larry, still smiling with morphine, up the rock. By 2 we were at the summit; no helicopter in sight. We did see huge, billowing storm clouds all around. The temperature was dropping rapidly, and my hair stood up with electricity, which meant you were coming.

I got on the radio and yelled at the sheriff. "Where the hell is that chopper? We're at the top. We need it now!" Nothing.

Cold rain pelted down. The temperature had plummeted from 70 degrees to 45, and the wind began to howl. We dragged Larry under an overhanging boulder and said good-bye.

"Sorry, buddy, nothing more we can do until this storm passes. Don't worry, we'll be back."

With that Dave and I scrambled off the summit looking for shelter. I tucked under a large boulder and curled up in a ball as your lightning began hitting the adjacent spires. Blue and white streaks of electricity crackled down walls pouring with water. Good show, God!

As the storm advanced along the ridge, it intensified. I watched in awe as the lightning struck the peak just to the south of me. Baaang!

That's the last thing I remember. I awoke to hear Dave shouting my name. "Eric! Eric! You OK?"

I looked over in the direction of his voice but all I saw was blue. Left? Blue. Right? Blue. Up ... down? Blue. I pondered this phenomenon as I tried to piece together where I was. Oh, that's right ... there was a storm. I must have fallen asleep ... Now the sky is blue. No more storm. But why is everything blue ... ?

Two big medics reached for Larry and hauled him aboard. As I stepped forward, the door closed, and the chopper took off. "Hey! Hey! What about me?"

Dave kept calling, pestering me. "Eric! Are you alive?"

I tried to get up but had no idea where up was, so I sat again. Very slowly you took the blue blindfold off me, and there was a fuzzy image of rocks and clouds and ... Hey, there's Dave, huddled under a rock 100 feet away. As my vision cleared, I started to remember things. Larry, where's Larry? Is the storm over?

I rose unsteadily and staggered toward Dave.

"You got hit!" he shouted. "You got hit by lightning. It hit the rock and went all around you. It was unbelievable. I thought for sure you were dead."

Then I heard it: the helicopter. It had arrived just before the storm and landed in a small meadow at the base of the peak. Now it was hovering somewhere above us. Dave and I scrambled to our feet and headed up to Larry, still with a smile on his face. We grabbed him under his arms and with only the strength that lightning-fueled adrenaline can provide, dragged him to the very top of the peak.

Just as we got him there a crack in the clouds opened, and the helicopter appeared. It touched one skid down to the rock, and the side door slid open. Two big medics reached for Larry and hauled him aboard. As I stepped forward, the door closed, and the chopper took off. "Hey! Hey! What about me?"

Within seconds the hole in the clouds filled in, and hail fell. Hard. Wind whipped the marble-sized ice into lethal pellets. We ran across the summit to rig rappels.

Every time I almost get killed--and that's not even counting the ones we both know I've glossed over (including the time I came to after a lightning strike to see a little girl, whom I'd grabbed to hasten her down a trail, staring at me, asking, "Were you dead?"), someone says, in one fashion or another, "You're obviously still here for a reason. God is watching out for you."

So I'm trying to figure out exactly why you keep me around. Although I occasionally do good stuff, I'm not a saint. I guess I've got some organs you could use if you find someone nicer who needs a spare part. Perhaps you intend to use me as an example: Don't be bad like him or I'll whoop your ass, too.

No, I think I've finally come up with the answer: comedy. You enjoy pulling all these stunts on me. You're just showing off for the angels! I bet they're really having a hoot up there on Cloud 9, eh? What about when you don't have me to kick around anymore, at least down here? Do you really think there's another knucklehead as understanding as I am? Think about that. Now I better hit send, because you never know what's going to happen. Actually, you do.

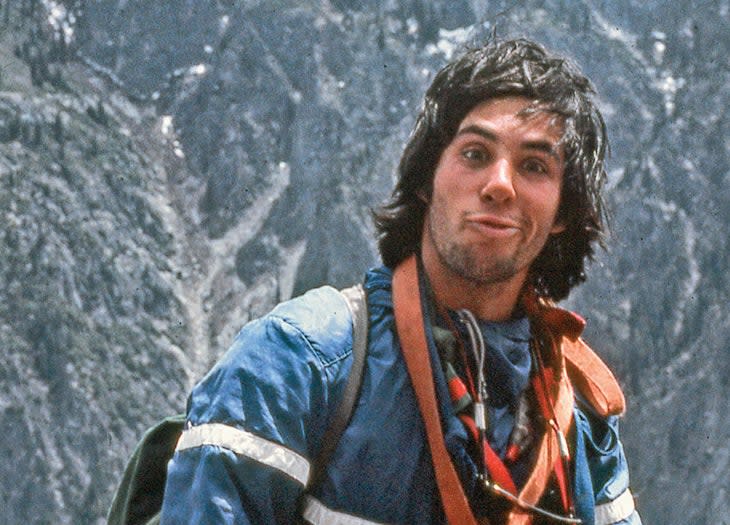

Eric Sanford survives in White Salmon, Washington.

This story first appeared in Ascent 2018.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.