The Creator of American Sportswear Who Time Forgot

Bonnie Cashin retired from design 35 years ago, but her legacy still dictates how women dress.

About three months ago, I was knee-deep in some reporting about how those saggy canvas tote bags are obliterating our skeletons when I came across a name that made me pause, Google and then Google again. Perhaps you read the piece when it was published, and perhaps you had the same reaction as I did, which came on quickly and rabidly and introduced a fascination I can only describe as relentless.

The name? Bonnie Cashin, a pioneering ready-to-wear designer whose mid-century contributions to the fashion industry helped invent, and cement, the category of American sportswear. And yet, my fascination was this: I genuinely had no idea she existed until a historian told me so.

Apparently across the Bonnie Cashin Awareness Society, I'm more the rule than I am the exception. It’s been 20 years since her death, and her legacy still dictates how women dress and, in turn, how designers dress us. But that impact has gotten lost in time, buried beneath the very same mountain of practical, accessible wardrobe staples she introduced in the first place.

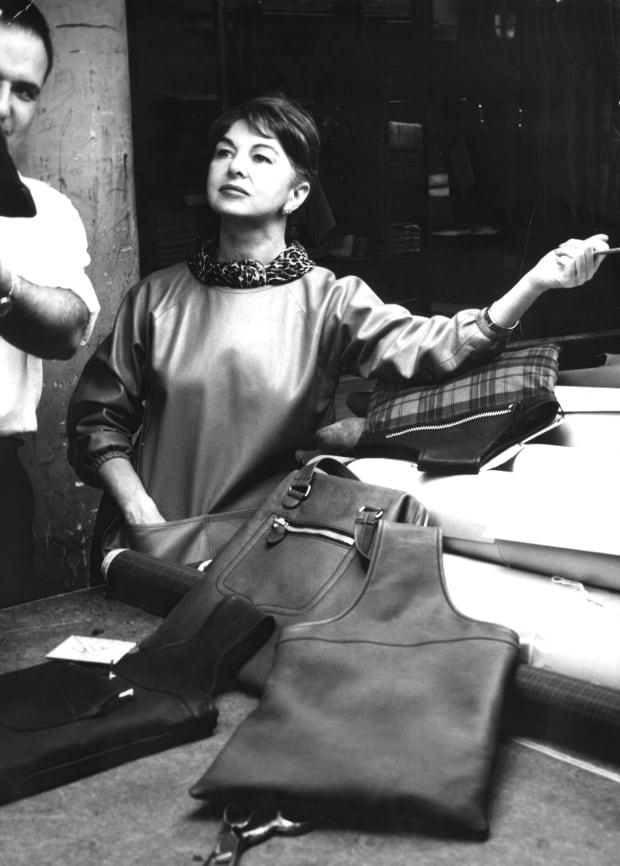

Cashin's influence on American design — and on sportswear in particular — is tremendous. In fashion, she's often credited as the inventor of "layering," both the concept and the term. She was among the first to use metal hardware in clothing and accessories, and to combine leather and fabrics in the same garment. She designed the first-ever goddamn flight attendant uniforms for American Airlines!

Though, the more I read up about her life, the more dizzyingly desperate I became to answer two questions: Who was Bonnie Cashin, and how exactly did she become one of the U.S.'s most influential fashion designers that popular history forgot?

The answer to both those questions appeared 1,200 miles away in the hands of Dr. Stephanie Lake, a jewelry designer and decorative-arts scholar who lives in Minneapolis. As Cashin's biographer and sole owner of her personal design archive, Lake is also the designer's literal heir. Today, she oversees a collection vast enough to be considered a private museum. Among her other Cashin-adjacent duties, she runs the Instagram account @cashincopy, which charts contemporary iterations of Cashin's designs and places them side-by-side the original pieces.

Lake's introduction to Cashin was similar to mine in that she was entirely unaware of Cashin's personhood until she came across some research that made her presence known. It was 1997, and Lake was working as a research consultant at Sotheby's when one of Cashin's designs came across the Sotheby's floor.

"I had never heard her name, so I started to learn about her and I was shocked that I wasn't just pulling a book out of our reference library, a Bonnie Cashin monograph," says Lake. We've scheduled a phone call that she takes from her home office, within a floor devoted to the Cashin archive rooms and her own design studio. "I was absolutely shocked that that didn't exist."

One degree of separation led to another, and soon enough, there she was at the source: sitting in Cashin's UN Plaza apartment. The two became fast, fierce friends — so fierce, in fact, that upon Cashin's death three years later, Lake was surprised to learn that Cashin had entrusted her entire design archive, as well as a vast amount of her personal estate, to Lake and Lake alone.

Lake swiftly learned that Cashin was the kind of fabulously madcap, Interbellum Generational icon who just didn’t come around anymore.

Cashin was born in Oakland, Calif. in 1908 to a swirl of creativity: Carl, her father, was a photographer and inventor, while Eunice, her mother, was a dressmaker who opened several custom dress shops throughout Cashin's childhood.

By high school, the family had settled in Hollywood, at which point Cashin was hired as a costume designer by legendary ballet and revue company Fanchon and Marco. In 1934, Cashin moved with the company cross country to New York, but returned to Hollywood 10 years later, this time with a blue-chip 20th Century Fox contract. In just six years, she produced the clothing for roughly 60 films, including 1945's Oscar-winning production of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Related Articles

In the Always-On Economy, Workwear Is Getting a Fashion Upgrade

The Symbolic, Practical and Sometimes Painful History of the Commuter Bag

Fashion History Lesson: The Real Story Behind Fake Fur

Then, at age 41, Cashin bid adieu to Hollywood, both literally and figuratively, and began Act II.

In 1949, Cashin was back in New York designing her first ready-to-wear collection under her own name. The debut received a windfall of acclaim: In 1950, she won both the prestigious Coty Award (alongside fellow recipient Charles James) as well as the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award. She opened her own business, Bonnie Cashin Designs, in 1951.

Cashin was not designing costumes anymore, and that was the point: It was time to infuse some good 'ol Yankee practicality into what was then a decidedly unpractical way of dressing.

In 1932, retail magnate Dorothy Shaver — one of the first American women to head a multimillion-dollar company — was working as Lord & Taylor's vice president of style, publicity and advertising when she created a program, called the "American Look," to support the work of American fashion talent, the pool of which would later include Cashin.

The American Look challenged the status quo that all of fashion — its mores, its trends — came from Paris, and that all of womankind was expected to keep up accordingly. So as Christian Dior was presenting his "New Look" from Paris in 1947, a growing legion of women in the U.S. were also announcing their dissatisfaction with the same style's impracticality.

"Women had been out in the workplace while men were at war," says Cynthia Amneus, chief curator and curator of Fashion Arts and Textiles at the Cincinnati Art Museum. The institution regularly features Cashin's work, and in 2015, put on a pop-up exhibit that chronicled her life and career. "Women were wearing coveralls. They were in pants. Suddenly, Dior took them back to corsets and structured clothing and nipped-in waists."

It wasn't that women were entirely shunning Dior's interpretation of femininity. It was just that we, as ever, wanted options.

"I mean, everybody wanted to go back to that, to some degree — to look feminine"” says Amneus. "Women wanted to look beautiful. Men wanted their women to look beautiful. But Cashin and other American designers were saying, 'Hey, we want to be comfortable.'"

There we have it: sportswear! It's extremely difficult to separate the definition of sportswear — "coordinated separates that could be easily mixed and matched," per WWD — from Cashin's respective work. One informed the other as much as someone like James Jebbia or Virgil Abloh has animated streetwear. Sportswear's comfortable, laid-back designs also came to represent the middle class, particularly throughout the suburban shift of the Forties and Fifties.

If Cashin had one iconic design job — and she had a lot — it was at Coach. In 1962, Coach's co-founders Miles and Lillian Cahn hired Cashin to spearhead a brand-new women's accessory business under their men's accessory company, Gail Leather Products. Internally, the brand was even known as "the Bonnie Cashin account."

In 1969, Coach released its Cashin-designed shopper: a zip-top tote that came in three different sizes and was specifically engineered to carry another smaller handbag inside. (Coach now sells a reproduction of one of the original "Cashin-Carry" bags for $550.) Cashin popularized the bucket bag, too, as well as the brand's signature turn-key hardware that remains a house design staple.

"[Cashin] was the designer who started the movement of carrying two bags to work," Jeannine Scimeme, adjunct assistant professor in Accessories Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), told me this fall. "It was definitely for busy, working women. If she carried two bags, that woman was working outside the home. And [Cashin] believed that women had so many roles, one bag wasn't enough."

That's the sound bite that set me down this path of mystery-solving: that women in their new, post-war realities needed coats and bags, shoes and skirts that covered just about everything in their daily lives in a way that was as chic as it was accessible — traveling to and from work, of course, but also picking up and dropping off children, having lunch, running errands.

"Bonnie Cashin created that," says Amneus. "The whole idea of separates, of going into your closet and saying, 'I'm going to wear this jacket with this skirt with this blouse,' and it not being a set ensemble. It's how we dress today, but people don't understand where it came from."

When I ask Amneus why Cashin has largely evaded household-name recognition, she replies that the answer is right there in front of us: It's how we — not like, Audrey Hepburn — dress today.

"Even though she was revolutionary in what she was doing, nobody knows who she is because she was designing sportswear. You know who Valentino is, who Dior is, who Balenciaga is — all the high-end, highly-visible designers. But you don't know the every day. Sportswear has gained some traction in the world of fashion, but at the time she was doing it, it was more casualwear, and so it was under the radar."

Would Cashin even have wanted to sit above the radar, though? I ask Lake. For her work, her affect, her legacy, certainly. But for herself, absolutely not. Cashin was a notoriously private person, and Lake describes that this sometimes presented as an iciness.

"She worked as an artist," she says, "and she was not interested in just having people fawn over her." She never registered her own name to prevent licensing throughout and after her career, after her life. Cashin passed away in 2000, and Lake still owns and controls 100% of Cashin's archive.

"She was very interested in how others could benefit from what she did, how she did it and from the archive that she left behind," says Lake. "The scope was so much bigger than putting a name onto an object. I think in some ways, she made sure that her name posthumously was not where the greatest value is. It's her story, it's her collection, it's her impact. It's not distilled down to stamping a name onto something."

One of the chapters of her own story that Cashin valued most was her Innovative Design Fund, a New York-based nonprofit organization she founded in 1979. The program effectively served as an early-stage design incubator, awarding scholarships to creatives with original ideas in home furnishings, textiles and fashion so they could bring their prototypes to market. It was not dissimilar from the flood of accelerators for fledgling designers that now peppers markets all across the world.

"It does just become one jaw-dropping moment after another where you realize how early she did things and that she is the point of origin for so much," says Lake. "History is not just some marvelous, magical thing that just happens. It's completely shaped by so many forces. And Bonnie was one of them in the fact that she was interested in telling her story, but she wasn't interested in diverting her energies from the central joy for life, which was design."

Minutes after Lake and I wrap up our call, she sends along a follow-up email that includes a scan of handwritten note, messily, seemingly hastily scrawled across a piece of scrap paper. It's from Cashin, obviously, who's coming at my inbox from the great beyond with the following message:

Creativity is like love — the more you give, the more there is. The multiplication is unstoppable, the thirst is unquenchable. Of course neither works in a vacuum — the climate for both is variable — but where there's a yearn there's a way.

Maybe time didn't quite forget Cashin. Maybe her work simply multiplied, and maybe it was unstoppable.

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.