Covid: The Microbe That Changed the World

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

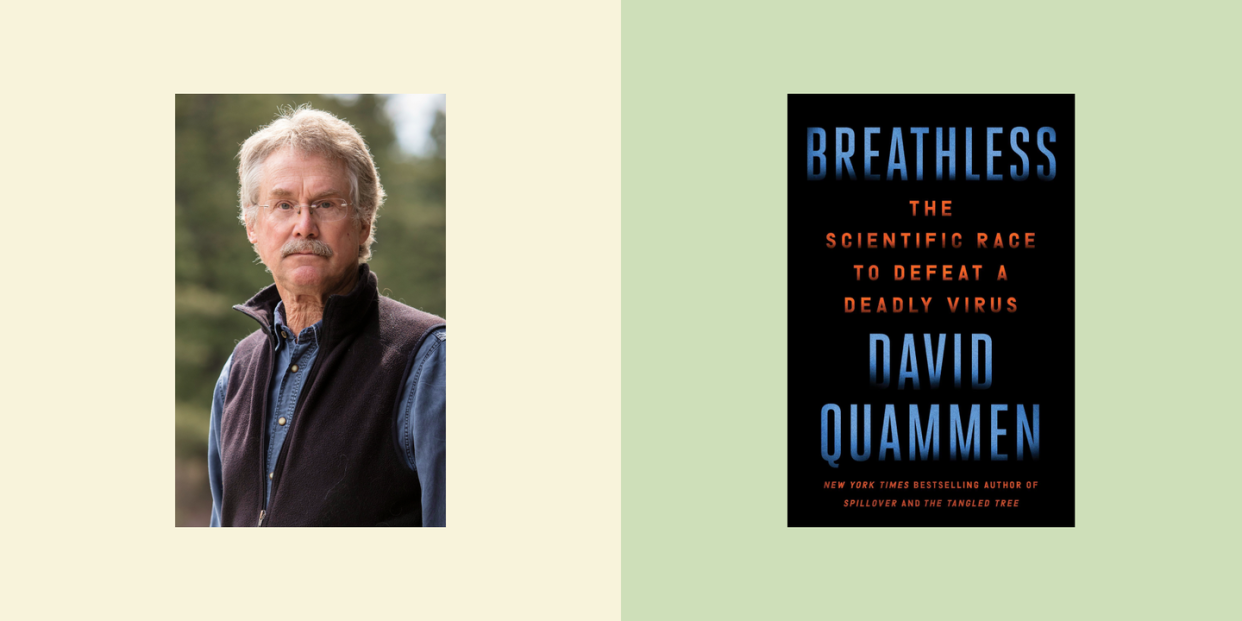

On New Year’s Eve 2019, as midnight revelers watched the ball drop in Times Square, clinking flutes of champagne amid strains of “Auld Lang Syne,” clinicians in Wuhan, China, were buzzing online about a sharp uptick in severe pneumonias, many traceable to a wet market that specialized in wild game, a cesspool for viruses and bacteria. Patients rolled into ICUs ventilated, their lungs drenched in fluid. As the eminent science journalist David Quammen recounts in his sweeping, deeply reported new book, Breathless—a finalist for 2022’s National Book Award in nonfiction—the microbe that changed history had long been predicted, but it still caught the world by surprise.

Unlike his previous books, Quammen composed Breathless behind his laptop, in the quarantined comfort of his Montana home, sorting through Zoom transcripts, phone interviews, and messy data. A few of his headlines are familiar from press reports and Lawrence Wright’s estimable The Plague Year, published last year, just before the Delta wave. The ancestral virus likely emerged from a spillover zoological event, probably in the autumn of 2019. (One of the book’s many merits is Quammen’s meticulous unpacking of the lab-leak hypothesis.) Genomic studies revealed that it had circulated among bats, possibly infecting an interim species, such as pangolins, before jumping to humans. Along the way, it acquired key mutations in the spike protein, which allows the virus to latch onto cells and infiltrate them, churning out copies of itself and spreading across the respiratory tract and other organs. By the time researchers had determined that the coronavirus could pass from person to person, it had already hitched rides aboard aircraft to Japan, Europe, Iran, and the United States. From Wuhan to Milan to Sao Paulo to New York, patients surged into hospitals; sirens shrieked around the clock. By mid-March, the world had locked down.

The Chinese government tried to bottle information, but a cadre of brave, punctilious scientists snapped into action on WeChat, ProMed, and other websites, sharing data, trading interpretations, and publishing the sequenced genome. Quammen beautifully evokes that “all hands on deck” choreography. The DNA closely resembled that of the first SARS virus, which had blazed across Southeast Asia and Canada in 2003 before rapidly burning out. “They also viewed it by electron microscopy,” he writes, “which showed the corona of protein spikes, protruding like cloves in a roast ham, that gives the viral family its name.” Another unusual trait jacked up rates of transmission: An infected person could shed virus even without symptoms. The World Health Organization declared an emergency as SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) blew up, trailed by Covid (the disease) and fatalities.

Thus commenced the worst pandemic in a century. Breathless builds suspense and drama throughout its early chapters, the false moves and authentic leaps as the global scientific community kicked into high gear. Quammen balances the gravitas of his topic with conversational wit, drilling deep into his characters, from the famous and camera-ready to behind-the-scene players, such as Dutch virologist Marion Koopmans and Barney Graham, a Kansas farm boy turned lab magician. Quammen’s flair shines a light on the alleys and detours knotted amid the foreground plot, among them the backstory of HIV and the politics that often chafed against the science.

The later chapters home in on the collective miracle of the vaccines: Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer. Quammen can’t help getting technical in these sections, but he sprinkles in cheeky humor that leavens the mood, as in an aside about ivermectin, which Trump endorsed for Covid treatment. As Quammen observes, “Ivermectin is available over the counter, at your local pet store or feed store, or from Amazon with a couple of clicks—in tablet form, chewable tablets, pour-on liquid, or as an apple-flavored paste, all intended for deworming your dog, your horse, your cows, or your goat. That’s because it’s an important and trusted tool among veterinarians and livestock producers for treatment against lice, mites, and parasitic worms. Then again, the claw hammer is an important and trusted tool among carpenters, but it’s not recommended for use in dentistry.”

And as he reminds us, it ain’t over until it’s over. SARS CoV-2 afflicts us still, spawning variants that continue to raid the Greek alphabet, right up to Omicron and its daughters. With each twist of infection, these variants grow ever more robust, outflanking defenses like natural immunity and mRNA vaccines. Wealthy nations have often hoarded resources at the expense of the developing world—not only a moral travesty, Quammen notes, but a medical one as well: “There is no lasting herd immunity except for the human herd.”

We’re running hard to keep up, but to quote a physician friend, Mother Nature always bats last. If we’re lucky—big if—SARS CoV-2 will settle in like seasonal flu. Until then, we’ll rely on the literature of Covid to make sense of it all. Breathless, then, is an invaluable, vibrant contribution to that literature, arguably the single most comprehensive account of the disease and the clinicians who have labored long and hard to divine its mysteries.

You Might Also Like