COVID-19: What changed in four years since pandemic was announced?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The world likely wasn’t paying that much attention on March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared already-worrisome COVID-19 a global pandemic. But that coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, would soon change world economies, business practices and how health care systems and even schools operated. New and repurposed phrases in the U.S. would soon become part of everyday language in coming months: “masking,” “social distancing,” “flatten the curve,” “quarantine” and “remote work.”

COVID-19 would forever change individual families, too, as the death toll climbed into the millions worldwide.

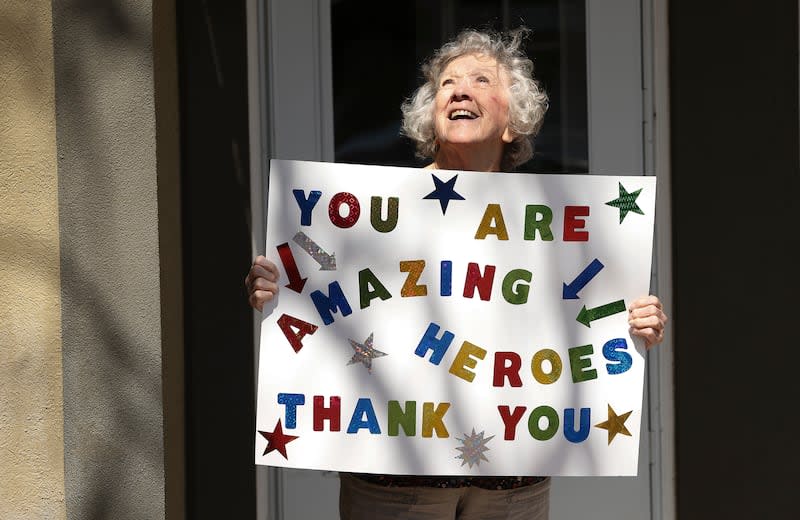

The fourth anniversary of that pandemic declaration this week is a reminder of how it reshaped the world in profound ways. We better understand preparedness and resilience. We witnessed the vital role of science and research. We found more appreciation for public health and health care workers. We figured out that mental health matters. We saw the value of technology for remote work, education and social connection.

We learned a lot about disease spread and building vaccines fast, about lost jobs and opportunities. We also gained insight into social isolation, the nuclear family and how to put one foot in front of another on a very unfamiliar path. It’s a time to look back, review what happened, and then look forward and commit to keep going when crises inevitably come.

Shutting down

The highly contagious virus had already been declared a public health emergency in the U.S. and three big airlines had already suspended flights to mainland China because of the outbreak there. But despite stories about virus-related illness and death in nursing homes on the West Coast and a deadly outbreak on a cruise ship, U.S. news cycles that morning seemed more taken with the previous night’s Democratic primaries, which nudged Joe Biden along the path to presidential nominee, and the sentencing of film producer Harvey Weinstein for his rape and sexual abuse conviction.

Still, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus’ words to the media that morning were stark: “In the past two weeks, the number of cases of COVID-19 outside China has increased 13-fold, and the number of affected countries has tripled. There are now more than 118,000 cases in 114 countries, and 4,291 people have lost their lives. Thousands more are fighting for their lives in hospitals. In the days and weeks ahead, we expect to see the number of cases, the number of deaths and the number of affected countries climb even higher.”

The mysterious illness — best course of treatment unknown, details of its origin unclear, how to stop its spread unmapped, symptoms all over the place, no vaccine available — “can be characterized as a pandemic,” Tedros said. A coronavirus first.

Later that day, Tom Hanks announced he and his wife, Rita Wilson, had contracted COVID-19. That night, President Donald Trump addressed the nation regarding COVID-19. And as Deseret News’ Sarah Todd was covering the Utah Jazz vs. Oklahoma City Thunder, officials sent the gathered crowd home on news that Jazz player Rudy Gobert had tested positive. Soon, the whole NBA season was suspended.

Tedros, standing at his podium, reported 81 countries had no cases and you could count those detected in 57 countries on your fingers. There was time, he cajoled, to “change the course of this pandemic.”

That was a Wednesday. By the weekend, employers and schools were sending people home and businesses were closing. Some never reopened.

At the pandemic’s fourth anniversary, Worldometers reports the U.S. has had 111,638,262 confirmed cases of COVID-19, though it’s clearly a major undercount. Most of us told bosses or schools, family or friends if we got COVID, but aren’t in an official tally. There have been 1,217,245 U.S. COVID-19-related deaths as of March 13, 2024. Those numbers include 5,719 deaths in Utah, of its 1,136,008 reported cases. Nationally, the death count includes 25,996 in the Veterans Administration health care system, 2,268 in the Navajo Nation, 689 in the U.S. military, 324 in federal prisons and seven on the Grand Princess cruise ship.

The New York Times this week made the case that the death toll is much worse than indicated. “The Economist magazine keeps a running estimate of excess deaths, defined as the number of deaths above what was expected from pre-Covid trends. The global total is approaching 30 million.”

A new Lancet study reported the average life expectancy globally dropped by 1.6 years during the pandemic′s first two years. Among high-income nations, the U.S. fared especially poorly, with the highest excess mortality rate in 2020 and 2021.

An unmapped journey

The pandemic was so serious in New York City for a while that nurses were borrowed and bodies were sometimes stored in portable morgues. Overall, New York had 7.5 million cases and more than 83,000 deaths. But it wasn’t the hardest-hit state. Per Worldometers’ statistics, that was California, with 12.7 million cases and more than 112,000 deaths.

Schools went online. Airlines stopped flying to certain countries. re banned entry of noncitizens who had visited 26 different European countries within two weeks of arriving in the U.S. Millions of workers were sent home unless their in-person presence was deemed essential. And the government responded with stimulus money, financial aid for businesses and other help to reduce potential for an economic meltdown.

Two months after the pandemic declaration, Deseret News did an in-depth story on a Grantsville, Utah, husband and father of four, Justin Christensen, then 42, who had been hospitalized for more than two months after becoming sick with COVID-19 on a family trip to Disneyland. For most of that time, he was gravely ill and doctors at University Hospital described feeling their way along a basically uncharted treatment path to save him. They succeeded.

“Doctors are still figuring out how to treat the disease, which has no proven cure. The challenge is great because COVID-19 attacks patients differently; care varies even from room to room in the same hospital. It’s still largely a matter of managing each complication that arises. As the Christensens were about to find out, COVID-19 can change quickly from a distant news story to a battle for survival,” the 2020 article said.

Doctors nationwide were using therapies proven for other illnesses, sometimes boosted by experimental treatments like hydroxychloroquine, described as an “antimalarial long shot” that fell from favor for COVID-19. Though most cases had relatively minor symptoms, so many people needed critical care that they quickly outpaced available medical equipment. States, including Utah, drew up crisis standards of care guidelines to prioritize who’d access tools like ventilators should such decisions be required.

Shortages complicate COVID

So much happened in a very short time.

The disease seemed to ravage older people, so those 60 and older were told to isolate if they could. Visitors were locked out of assisted living, long-term care facilities and hospitals. Families were told to avoid group gatherings and especially older relatives. In a world that needed comfort, hugging and even handshakes stopped.

Meanwhile, local health departments were taking on additional staff to help with contact tracing and governments and public health experts made backup plans as case counts grew. Part of Utah’s backup plan included turning an expo center into a temporary hospital for up to 1,000 patients, complete with a pharmacy.

The pandemic was just two weeks old when Deseret News reported that shortages of lab tests, protective gear and other necessities “have made a severe crisis even worse, with officials begging for help. For example, people who purchased masks, gloves and other protective equipment for personal use early on are asked — along with primary care doctors, veterinarians, dentists, construction workers and others who might have their own supplies of certain types of masks — to donate them to providers for the public good.” Some businesses diverted to manufacture personal protective equipment for health care workers, but even so, non-emergency medical procedures were canceled. With massive need for testing, lines of cars wound into drive-through clinics. Testing supplies and lab capacity was inadequate. In early May, at-home saliva-based testing eased some of the testing angst.

Simple mask designs were created so those who could sew could make their own, even as folks were scouring empty store shelves for toilet paper and hand sanitizer. The entire country learned to obsessively wash their hands while humming the Alphabet Song twice.

Two months feels like eternity when the world shudders. In April, the White House came up with “gating criteria” to reopen the economy, based on achieving “benchmarks” reducing illness and deaths, as noted by an American Journal of Managed Care timeline.

In reality, 2020 was a scramble: to make the right public health recommendations, to find the right medicines, to craft better COVID-19 tests, to create vaccines. The latter was actually surprisingly swift, in a government/pharma push nicknamed Operation Warp Speed. As early as May, dozens of vaccine candidates were being considered, including eight already in human trials. By early 2021, three vaccines in the U.S. had fast approval and government contracts for millions of doses.

There were reversals, too. The CDC said masking wouldn’t help. Then everyone was ordered to mask. Experts said the virus spread by touching surfaces, but wasn’t airborne, which it proved to be.

COVID-19 was on a rampage through it all, gathering speed. On June 10, the U.S. hit a 2 million confirmed COVID cases milestone. By Aug. 17, COVID-19 was the No. 3 cause of death in the U.S., behind heart disease and cancer. And each viral mutation brought new degrees of contagion and severity.

Worse, more than a year in, some people couldn’t seem to shake symptoms after surviving the virus. In October 2021, WHO released a clinical definition of “long COVID,” including lingering symptoms. Some are quite serious, including terrible fatigue, brain fog, chronic pain, shortness of breath and chest pain. While not a health catastrophe, losing one’s sense of smell was often cited as a major disappointment.

How COVID-19 changed health care

Health care delivery changed in many ways due to the pandemic, hospitalist Dr. Russell Vinik, chief medical operations officer at University of Utah Healthcare and associate professor of medicine at the U., told Deseret News this week. He thinks some of those changes will last.

Telehealth is a big one. Before the pandemic, visiting with a practitioner by a video link was done primarily for low-acuity urgent care, like a urinary tract infection. Pre-COVID, mental health was also making small inroads in telehealth. But generally, 1 in 100 patient-provider consultations were remote. In the pandemic, it zoomed — literally.

“During the early day in the pandemic, those telehealth systems really weren’t built out to be able to handle it. But we did the best we could so we could take care of patients virtually. What we saw was a very dramatic increase,” he said, noting at least half of patient appointments were telehealth.

That was aided by the fact rules were changed to encourage virtual visits to avoid COVID-19 spread.

While telehealth visits have dropped dramatically to about 1 in 10 or 1 in 12 visits now, they’re certainly no longer 1 in 100. “We’re still probably 10 times higher than what we were pre-pandemic, but significantly lower than those peaks,” Vinik said. And some areas, like mental health, still make robust use of telehealth, maybe as much as 40%, he added. When the care provider doesn’t need to touch the patient, to give an injection or perform a physical exam, care is more amenable to telehealth than when those needs exist.

Masking also changed, Vinik said. “With the exception of maybe our chemotherapy patients, mask utilization was very rare. We’ve learned a lot and I think a lot of us recognize, if I get the sniffles, I should wear a mask. We certainly see a lot more of that now than we did pre-pandemic and I think that’s a good thing.”

He noted that while rules are less restrictive, where patients are the most vulnerable, like neonatal intensive care, “we encourage a lot more mask utilization.” But the culture changed, too. “The pandemic made it somewhat normal and people realize wearing a mask isn’t so terrible.”

Some changes are less welcome, the doctor said, including vaccine skepticism. Even vaccines around for decades may generate skepticism and he noted COVID-19 “propelled an even bigger debate about vaccines,” in part because during the pandemic new methods of making them developed.

One of the tragedies still impacting health is delayed screening. At the height of the pandemic, mammography dropped by over 50%, while colonoscopies fell as much as 80%. The cancers themselves weren’t suspended, just the search for them. So cancers were detected at later stages, Vinik said. “Patients suffered because of that.”

Lessons continue, Vinik said. “We had a pandemic where young, healthy people were dying every day right in front of us. We made the best decisions we could at the time to protect and contain this disease. This is where we learn from it and try to move forward.”

He said we learned “a ton” on the medical side about rapid development of treatments and new tools like mRNA technology that will be helpful in the future. Using antibodies to treat disease was very new and will continue to grow, along with knowledge of how disease propagates.

Failures and sorrow also emerged. “We have this legacy of depression and substance abuse which clearly worsened during the pandemic. It’s really probably too soon to tell if we’re ever going to get back to our pre-pandemic baseline. And we hear all the time about kids that went through junior high and high school, isolated from their friends. How are those kids going to do?” Vinik asked.

Then and now

It’s hard to talk about the pandemic in the U.S. without talking about politics. Pretty early on, political divides erupted centered on COVID-19 policies, probably in part because it was an election year. And some of the division lingers. Even now, folks are divided on vaccines or wearing masks. There are debates about stimulus packages and policies passed when people were losing jobs, businesses and schools were closing and it seemed the economy might rupture. Both liberals and conservatives have criticized the handling of the pandemic.

Liberals say that refusal to be vaccinated led to more spread and more death. Conservatives counter that physically closing schools lowered test scores, which have never recovered. A National Assessment for Educational Progress said that happened in blue states and in red states. COVID-19 clearly disadvantaged school kids.

There’s also pretty broad agreement that a lot was learned, accomplished and managed in a short time. It was all hands on deck: scientists, doctors, politicians, public health, educators, store clerks — name a profession and folks had to step up. Crisis enlivened helpers.

Last May, the public health emergency for COVID-19 ended in the U.S. Just this month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said those who have COVID-19 don’t need to stay in isolation for five days after symptoms leave. We now often talk about COVID-19 like we talk about other more seasonal respiratory viruses. Stories refer to a “tripledemic” that includes influenza, COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV.

A pain, but no longer a panic.