If You Could Actually Stop Aging, Would You?

Is this the moment when we all stop getting old?

It’s a strange question yet a valid one to ask in our October beauty-themed issue, given not only advancements in cosmetics promoted as anti-aging but also new scientific thinking that treats aging as a disease — one with a cure just around the corner. Peter Pan, it seems, might finally realize his wish.

All summer long my social-media feeds were awash with images of gray hair and wrinkles from people who posted photos of what they or their favorite stars might look like decades from now using FaceApp’s old-person filter. Lady Gaga came out something like Lauren Bacall, Timothée Chalamet bore an uncanny resemblance to Barry Manilow, and Paul Rudd, who hasn’t aged in decades, looked exactly like Paul Rudd. It was all very amusing but also indicative of a sea change in how people view aging today — that is to say, some of us now see growing old as a novelty.

That’s partly because many people take better care of themselves through diet, exercise, and responsible lifestyles and therefore look younger later in life. Plastic surgery and injectables have played a role in the increasing prevalence of unripe façades too, for better or worse. But what if in our quest to look forever young we achieved the real thing, the ability to stop aging altogether?

“There is no biological law that says we must age,” writes Dr. David A. Sinclair in a fascinating new book called Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don’t Have To. Dr. Sinclair, a Harvard Medical School geneticist named one of the 100 most in influential people by Time magazine in 2014, has made headlines for his discovery of molecular causes of aging that are potentially reversible. One of his latest studies finds that aging is caused by the cellular loss of epigenetic information, which he compares to software that reads the DNA. In another study he and his team reprogrammed that information to make damaged optic-nerve cells of mice young and healthy again, thereby reversing blindness caused by acute stress, chronic stress, or aging.

“Thirty years ago we didn’t understand what causes aging, how the body controls the pace of aging, or how to measure it,” Dr. Sinclair says in an interview. “Now we know all three, and that’s happened only in the last five years.”

After identifying the genes that control longevity, Dr. Sinclair concluded that they were the same ones activated in healthy humans by exercise or intermittent fasting. “And we now realize the reason fasting and exercise are good for us is not because you get thin and you pump blood around your body; it’s because you’re turning on these longevity genes that provide protection against diseases,” he says. “If you develop molecules that mimic that, you can take a fat animal and make it as healthy as a thin one just by tricking it into thinking it’s been exercising.”

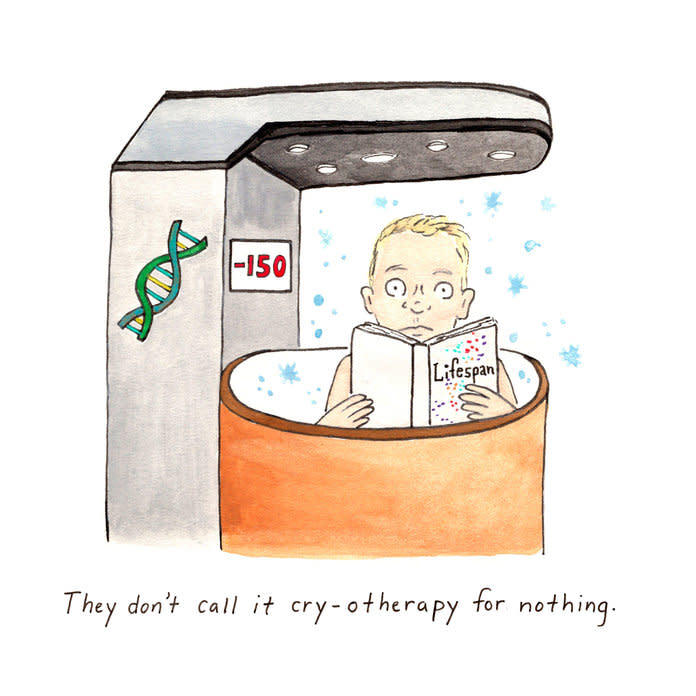

Skeptical? If this sounds too good to be true, Dr. Sinclair says we may not have to wait long to find out. About 20 companies are working on anti-aging drugs that might have practical applications within five years, he says. Of course, there are things people can be doing now. As part of his research Dr. Sinclair describes the possible benefits of less proven treatments, like sitting in saunas to activate heat-shock proteins or his own experience with cryotherapy, in which people subject themselves to extreme-cold temperatures.

“They fit with the idea of hormesis — what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” he says. “All I’m saying is that it’s not impossible that they are helpful.”

Reader, if it doesn’t involve needles and it might work, I’ll try anything once. My medicine cabinet is filled with serums containing enough ceramides, retinol, and hyaluronic acid to retain an ocean of moisture. Like many people, I was upset to learn that there’s a $3.6 billion skin-care market for children — not because Dr. Barbara Sturm is now selling mini-molecular baby face cream for $65 and shampoo for $50 a tube but because, back when I was a baby, I had to settle for Johnson’s baby shampoo, which cost just a few bucks. Stepping into a cryotherapy chamber at New York’s Equinox Hotel, I thought I’d use the three-minute chill at -150 C to consider the ethical ramifications of a post-aging world and the risk of overpopulation, and whether expensive new drugs will further augment societal inequalities. But the cold was so numbing that, $74.70 later, I could hardly count to four.

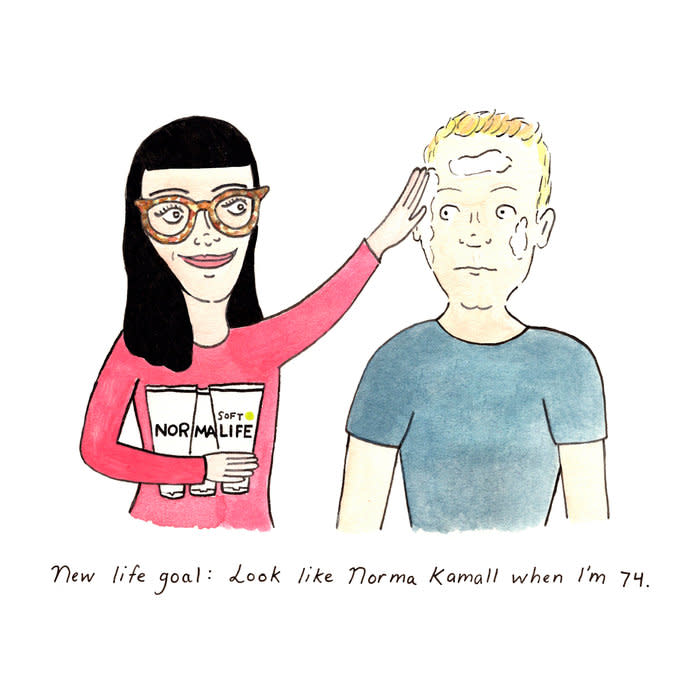

If there’s anyone I trust on the subject of aging, it’s designer Norma Kamali. She’s 74 and doesn’t look a day over 47. She’s just as obsessed as I am with the new science, but she’s on a bit more solid ground with her approach. Her unisex NormaLife skincare concept is as simple as a little black dress: a cleanser made with aloe and charcoal, an exfoliant made with finely ground olive pits, and a moisturizer with olive oil and lime water.

“When they say you can live to 120, I think, ‘Why not?’” Kamali says when I test the line in her store on West 56th Street in New York City. “When I was 50, 50 was very old, but 50 now does not look old at all. There are all kinds of ways to reinvent yourself, and everybody loves wellness. It’s becoming a huge business, and whenever there’s a huge business, there’s also a lot of cuckoo stuff.”

Rubbing my hands with exfoliant, she asks how long it’s been since I’ve been touched that way by someone other than a significant other. Her products are designed to promote self-care, with instructions that require lengthy massaging.

My hands look as young as ever now thanks to Kamali. But she too hopes that we are at the dawn of a new age of aging, when all the lotions in the world might be replaced by a pill.

“I think what the future holds is so exciting,” Kamali says. “I don’t want to miss it.”

Dr. Sinclair believes that the world will be a better place and points out that rich countries in Europe and Asia with the longest life spans have also experienced population declines because of lower birth rates. The best-case scenario is that we live longer, smarter lives if we start thinking differently.

“We don’t have to accept aging as natural,” Dr. Sinclair says. “We can call it a disease or anything you want, really — it doesn’t matter. We just have to not accept it as a natural course of life.

For more stories like this, pick up the October issue of InStyle, now available on newsstands, on Amazon, and for digital download.