At All Costs

I was first diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome when I was 14. At the time, it felt like an admonition, something that the doctor told me through gritted teeth. After reading every detail I could find about why it felt like an uncontrolled ricochet would fire through my digestive system like a hand grenade’s explosion, I found a naturopath who confirmed that my phantom illness might be IBS. It was the mid-2000s, and so my parents, having been shamed for the medicine of their South Asian roots, opted to get a second opinion from a Western doctor. And there I was, at 14, being told by said doctor that irritable bowel syndrome was still a largely unproven phenomenon and that what I had was still a mystery to her—but, yes, my naturopath could be onto something. Years of stool samples later, allergy tests on my back like bee stings, I decided enough was enough. I’d take matters into my own hands.

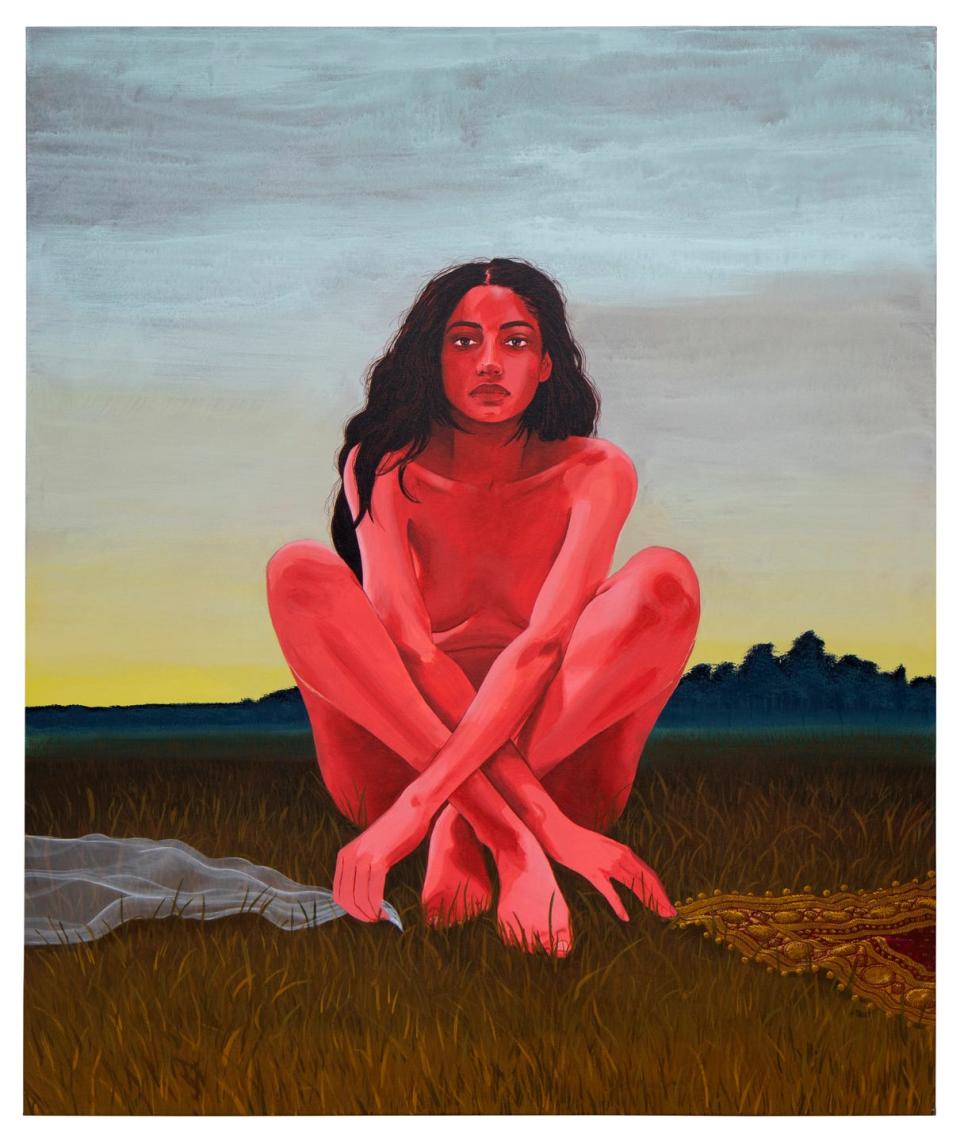

Growing up in a time when all information about the body had to be blindly assigned by a medical professional was difficult when you had a chronic condition that confused others. Somatic intuition was seen as quackery, and if I tried to describe the workings of my insides to doctors, they’d spend more time gaslighting me than actually listening to my perceptive wisdom. Sickness was common for not only me but also my sister, and we spent most of our teens turning our bodies into litmus tests for our own survival. I was constantly bloated, mucus stored in my throat so that every morning I’d wake up to a sea of phlegm pouring out of my mouth. Every time I’d blow my nose, snot dripped out like sap, and I’d wonder, who would ever marry me? It’s too simple to say I felt ugly. I felt like a bad equation, nonhuman, a person who was wrong in every sense. Femininity was beyond me, as was beauty; I couldn’t comprehend a time when I could be at peace with my physical body—a failing body that couldn’t even digest food, absorb nutrients. Instead, my physical self loomed in terror, becoming a punishing vessel for my already-lagging self-confidence. Dissociation can be such an abstract thing. If you’ve never felt at home in yourself, when do you know how to arrive into it? I’d never known how to feel safe in my own skin. Years later, I would understand that the reason I felt this way was that I’m a survivor of child sexual abuse. My body was always in revolt because it had never felt safe.

As I began my process of holistic healing in my 20s, what I started to realize was that so many of the practices I was gravitating toward—namely Ayurveda, meditation, and yoga—were rooted in my cultural lineage, and yet I couldn’t afford access to a lot of them. In my latest book, Who Is Wellness For?, I write about this paradox: how the disproportionately white wellness industrial complex profits off of Indigenous cultural and spiritual practices, only to then shut out members from those communities via class barriers and a lack of representation and accountability. As a result, it fails to understand the specific community needs of everyone. Wellness, for it to truly work, must be navigated with care, intention, and a decolonized approach. This means extricating it from capitalism so that customs and cultures are not abused for gross profit, isolating the very people that these practices are stolen from.

Years ago, when I was living in Canada, I volunteered at a white-owned yoga studio as a trade for classes. One day, during a busy afternoon class, the instructor, a white woman, came up to me and jabbed me bluntly with the stub of her finger and, more loudly than I would hope for, said, “You have a weak core.” It completely humiliated me, the only brown (let alone South Asian) woman in the yoga class. I was haunted by that experience, embarrassed, again, by the failure of my body.

In an interview with Studio Ānanda, an online community platform and social-art practice I cofounded to allow for conversations about wellness to be accessible, yoga teacher Lakshmi Nair explains, “The overemphasis on yoga for fitness and getting a ‘yoga body’ is colonized yoga. The emphasis in yogasana should be self-awareness and opening up and clearing energy channels.” I recently began learning about the chakras, the energy channels Nair is referring to. I read that when the solar-plexus chakra is blocked, it could be because of a lack of self-worth, a lack of value in oneself, which might manifest itself in IBS. “I think what is colonizing about the way Western yoga is usually taught is that it treats all human bodies as if they were the same or based on some idealized human body,” says Nair. “Western medicine is like that too. That is generally the colonized approach. I think the Indigenous approach respects the vast diversity of creation.”

That was one of the main findings from my own healing journey—that my people had the answers for the mysteries of my body. What has happened in the commodification of my people’s practices is that we’ve forgotten that caring for yourself is caring for the community and that those things should be interconnected. The pursuit shouldn’t be for aesthetic gain or capital gain; it should be about participating in something sacred, together, toward the divine. Remembering responsibility to one another is a part of yoga; it is a part of the ancient principles of my people that the wellness industrial complex has co-opted for its own gain. But I should know, there’s power in remembering, in reclaiming, in turning toward integrity. Sometimes it feels that’s the most necessary part about being human, about finding truth in your experience, and the only way you can do that is by facing yourself.

My IBS is a teacher; it’s become a miraculous guide toward understanding myself. It’s been humbling to remember there’s immense power gained from embodying. These days, I understand my life more complexly. I found perspective by wanting to hold and see all things equally—and, also, by trusting myself, my gut, and my own intuition.

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Harper's BAZAAR, available on newsstands May 3.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE OF BAZAAR

You Might Also Like