Coronavirus Is Making the Worst Part of Prison Even More Cruel

When Stacy Burnett was incarcerated, she played worst-case scenarios in her head on repeat. “You look out the window, and you see the traffic backed up, and you’re like, ‘oh my god, my kid is dead and no one's telling me,'” she said of when her pre-teen son was late for visits. Then there was the self-flagellation for milestones missed: “No, I don't remember that time your tooth fell out at the dinner table. No, I don't remember the time you crawled into the dog crate and couldn't get out,” Burnett says of conversations she’s had with her son since her release. “There is a reminder in the ensuing silence that I don't remember because I was ‘on vacation.’ Which is how he referred to my time in prison.”

According to data from the Prison Policy Initiative, women’s incarceration has grown at twice the pace of men’s incarceration over the last few decades. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of women in jail grew by more than 5%, though the overall population of inmates in the U.S. declined. Women of color are “significantly overrepresented” in the criminal justice system, with Black women representing 30% of all incarcerated women in the U.S., and Hispanic women representing 16%. And, according to the ACLU, two-thirds of female state prisoners are mothers of a minor child. Burnett was one of them.

“Family separation is traumatic for the entire family unit — especially children,” says Evelyn McCoy, a Research Associate at the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute. While the issue is not new (and is consistently traumatic), COVID-19 has placed additional stress on incarcerated mothers. Increasingly, prisons and jails are suspending in-person visits as a precaution against the spread of the coronavirus. Now, phone and video calls are the main means for families to keep in touch — but those options come with a cost many families can’t afford.

RELATED: What You Need to Know If You’ve Been Laid Off or Furloughed, or Fear You Might Be

“Visits can be a sacred time for families to be reunited and strengthen familial bonds, having a positive impact on a child’s behavior and mental health, and a mother’s wellbeing as well,” says McCoy. “Should a mother get sick and pass away, this has an enormous impact on the family unit,” she adds, pointing out that women are more likely to have been the primary caretakers of their children before entering prison.

"You have parents out there, and kids out there [of incarcerated women] ... and they're like, 'oh my god, are they gonna survive this?'" says Lynne Sullivan, a former inmate who now serves as a division manager of the Petey Greene Program, which recruits and trains volunteer tutors to support incarcerated students, and an advocate for incarcerated people. "They don't have the kind of care that you're going to need, not on the inside. And the only way to keep people separated is if you put them individually in cells and lock them in. So now you're putting them basically in closed custody — solitary confinement — because you're locking them in all day. Mentally, that's a form of torture."

Despite the suspension of visitors, the coronavirus has already infiltrated correctional facilities, and is spreading aggressively, according to Vox, mostly due to inmates’ close quarters and a lack of adequate cleaning supplies. Shannon*, a 47-year-old woman who is incarcerated in a medium-security women's prison in the northeast, wrote in a text to Burnett shared with InStyle that "people are sick and I'm pretty sure we're going on complete lockdown." Shannon's sister, Sarah*, tells Burnett that Shannon skipped her medications over fear of contamination, and ended up with heart palpitations. "I just sit here feeling powerless,” reads a text from Sarah to Burnett.

To quell the spread of the virus, some states have released inmates with pre-existing conditions. Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department is considering releasing pregnant women and older adults with higher risk of contracting the virus, and as of the end of March, six women and their babies were released from Decatur Correctional Center in Illinois. But a few successes here and there is not enough — not for the women incarcerated across the country, nor for their families.

“This is not the same as our self-isolation, lounging on comfy couches and binge-watching television,” explains Burnett, who now works as Recruitment Intake Support Coordinator at College & Community Fellowship, which enables women with criminal convictions to earn college degrees. “They are on their mattress, which is about as thin as a yoga mat, with nothing to do but obsess over whether the women in the adjoining cells are exhaling COVID-19, while they have no choice but to breathe it in.” She adds that a well-thought-out release is crucial to keep women safe — and that includes a plan for when they get to leave the facilities.

Georgia Lerner, Executive Director of Women’s Prison Association, which promotes alternatives to incarceration and supports women as they plan for release, says that women are coming to her organization for things they always need following their release, including access to healthcare, housing, reunification with their children, and services to help them manage mental health and gain employment. “What’s different now is that access to those things is lacking across the board and the most marginalized are bearing an even greater burden than before,” she says. The Association has heard of people coming home from jail or prison only to be turned away by their families over fear of COVID-19 spread. People are losing jobs, or not getting them, and systems are overloaded. “Women are leaving jail [sick] with COVID-19 and we don’t have the resources we normally have to connect them to medical care,” she adds.

RELATED: Young Women's Careers May Never Recover From This Pandemic

It isn’t challenging to see how lack of safe places for formerly incarcerated women, and lack of resources, impacts family separation. “We often think that when people go to jail or prison they are cut off from society — sent to a fortress on a hill,” says Stephanie Bazell, Director of Policy and Advocacy at College & Community Fellowship. “This could not be further from the truth. Women mother through jail and prison [and continue] to care for families and communities.” With visitation suspended, she continues, mothering is made even more difficult, which is why College & Community Fellowship is working with several other groups to fight for free phone calls for inmates who have yet to be released.

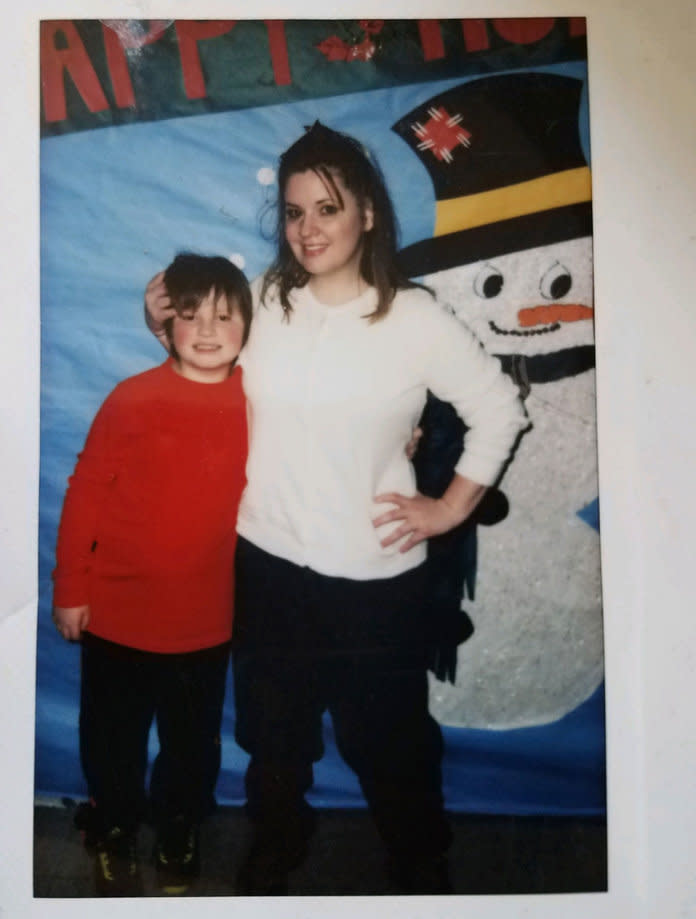

Stacey Burnett

Burnett says that about six months after her release, her son confided in her that he felt he needed to visit her in prison to ensure she was OK . Now 13, he explained that he had been told by officers that she received a strip search every time he came to see her, leading him to not want to visit because “he didn't want me to have to go through that just to see him.” Her son also always wanted to bring her food, convinced that inmates only received bread and water, and was concerned for his mother’s safety when she went to the bathroom, because he assumed that’s where people got beat up. “Those are the types of cruelties that are so casually flying about,” because of the misconception that permeates society about what prison is like, Burnett says. “And we don't realize what the long-term effects or ramifications [on children] are.”

RELATED: Why You're Suddenly Remembering Your Dreams in the Morning

Burnett sympathizes with women behind bars who are “alone, cut off and just terrified.” It’s why family reunification, in light of COVID-19, is so necessary. Women who have been incarcerated are human beings: daughters, sisters, friends, and mothers. “They spent their whole lives invisible,” Burnett says. “And now their lives are in jeopardy because to most people, they are invisible.”

While an overhaul of the system is the only real solution for protecting women and their families now and in the future, there is a little something that people can do from home: Stop the fear mongering about the “danger” of releasing inmates. “In the face of COVID-19, the right thing to do is bring people home,” Lerner says. “And then that begs the question, did they need to be incarcerated in the first place?”

*Names have been changed out of respect for subjects' privacy.