The Cooking Gene: An Appreciation

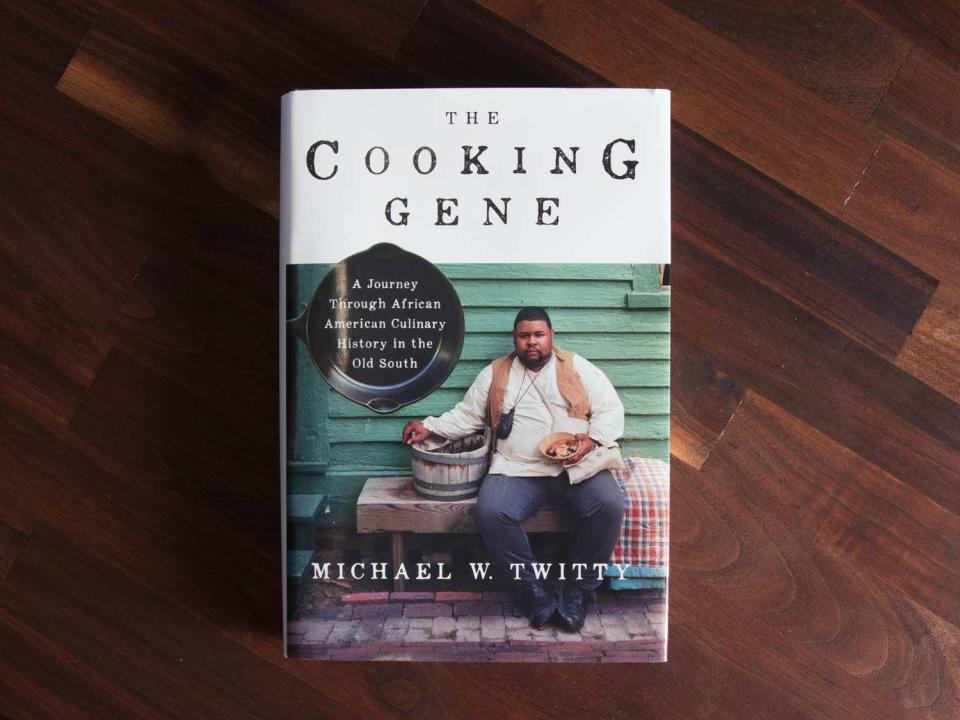

Michael W. Twitty's book The Cooking Gene belongs on every shelf.

The kitchen is commonly conceived of as a space of comfort, a place where love is regularly transformed into daily care and sustenance; it is where some of our most tender memories are created. The dangers, such as they are—the knives, the scalding oil, the open flames and the hot surfaces—we learn to avoid, allowing us to focus on the pleasant things: family, food, and the good feelings that arise from their combination.

But for many, it’s another sort of space entirely. In his book, The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, Michael W. Twitty describes the kitchen as a site of terrible trauma, one that, to this day, goes largely unaddressed.

"The kitchen in slavery was always a sinister place," Twitty writes. "The kitchen is where we acquired the eyes of our oppressors, their blood and bones and cheek-blush. The kitchen was, perhaps more than any other space during slavery, the site of rape after rape, sexual violations that led to one of the more unique aspects of African American identity—our almost inextricable blood connection to white Southerners."

Part cookbook, part memoir, part history, and part genealogical survey, Twitty’s book examines the debts contemporary American food culture owes to the enslaved and their descendants. Since its publication in 2017, it has justifiably received critical praise and a number of accolades, most notably from the James Beard Foundation, which honored the book with the Book of the Year and Best Writing awards. The Cooking Gene's recent release in paperback provides an occasion to make the case for why it deserves as wide an audience as possible.

Part of the project Twitty is engaged in, and has been engaged in for years with his blog, Afroculinaria, is drawing attention to the profound ways in which the history of African Americans in this country has shaped contemporary culture, and particularly Southern foodways. It can sometimes seem as if he’s providing a remedial education for his readers, going over ground that should have been covered extensively in US schools. As Twitty succinctly put it to me over the phone, "Black history matters." Anyone who knows that history knows the enslaved were routinely sexually assaulted, both in and out of the kitchen, but many Americans remain unaware of the scale of that violence, let alone its implications. Just after the above quotation on the kitchen, Twitty observes that the legacy of sexual violence is written in the lineaments of his face: "As Caroline Randall Williams, co-author of Soul Food Love, once told me, we’re 'rape colored, our trigger is the mirror.’"

In The Cooking Gene, the kitchen emerges as a space of both trauma and survival, and Twitty deftly uses it as a lens through which to understand and examine the broader history of the slave trade. Slavery and food were inextricably entwined: Twitty explains that because the enslaved were integral to the agricultural process, they became an agricultural commodity themselves, with the international slave trade timing deliveries of enslaved Africans to the Americas to correspond with the harvesting and planting cycles of corn, rice, and yams. Through this and countless other examples, Twitty illustrates the ways in which the horrors of the slave trade and enslavement fundamentally reshaped survival strategies, creating an entire population for whom the integrity of the family was under constant threat and the concept of heritage a cruelty.

Twitty writes, "So much was lost—names, faces, ages, ethnic identities—that African Americans must do what no other ethnic group writ large must do: take a completely shattered vessel and piece it together, knowing that some pieces will never be recovered." Twitty notes, "The food is in many cases all we have, all we can go to in order to feel our way into the past."

And so Twitty allows the reader to accompany him on an excavation of the African American past, using his own genealogy as a map. As he explores the different branches of his family—going back eight generations, uncovering the identities of his ancestors, both those brought to this country in chains from West Africa and those who forced themselves upon those they held as chattel—he simultaneously explores the way American cuisine was shaped by African American hands.

Twitty’s book doesn’t examine only the foodstuffs and foodways that we too often equate with African American cooking—those crops that accompanied enslaved Africans to America during the first Middle Passage (plantains, pigeon peas, sorghum, okra, et cetera), and those foods that fall under the imperfect umbrella we know as "soul food," like barbecue and fried chicken and cornbread—but also the rice grown with the farming expertise of West African natives, and their role in creating and preparing the haute cuisine of the pre-Civil War period.

""I present my journey to you as a means out of the whirlwind, an attempt to tell as much truth as time will allow.""

The Cooking Gene is not only a tally of the sins perpetrated against the enslaved and their descendants, nor is it just an illumination of how the forced movement of America’s enslaved population led to a vast and varied cuisine for which every modern American should be grateful. It is, in the end, Twitty’s stab at an answer to the question of what we do with this information. As he puts it, "We can choose to acknowledge the presence of history, economics, class, cultural forces, and the idea of race in shaping our experience, or we can languish in circuitous arguments over what it all means and get nowhere. I present my journey to you as a means out of the whirlwind, an attempt to tell as much truth as time will allow."

The day before Twitty received his Beard Awards, I spoke to him about the book on the phone. He noted that, originally, he had meant to end the book with a description of his journey to West Africa, a trip he ended up making after the book’s publication. As we were talking, he described visiting a kitchen on Gorée Island, off the coast of Senegal—one of several famous sites associated with the Atlantic slave trade—and experiencing a kind of catharsis that left him "crying and crying" for half an hour. He told me, "I remember feeling the pots, the firewood, the walls, and the blackened roof, and getting really emotional and very upset. It wasn’t like a feeling of 'Let me go, I don’t want to see this place.’ It was like, 'I thought I was never going to see this place again.’"

When I asked him to elaborate, he responded, "It wasn’t the familiarity of knowing the pieces and the parts and what they do. It was that this place was safe and it was home; this was the original kitchen table with grandmothers and mommas, this was the original space in which that kind of love and nourishing happens."

Much of Twitty’s work can be described as that of reclamation—of African American identity, of African American cuisine, of the security and comfort of the kitchen, and, above all, of the ownership of the largely white scholarship surrounding the African American experience. But it is in moments like the one he experienced in Senegal that one of the purposes of this reclamation becomes clear. It is an avenue for catharsis, a way to dispel the evil that is the product of ignorance, willful or otherwise.

In our conversation, Twitty observed, "People don’t go through the crucible; they don’t experience it, because they’re scared to. I think they’re scared of what will happen to them when they let go of certain things they hold on to out of stubbornness. They’re scared of experiencing the emotions that one gets when one stares down their past and their family’s past. When they think that they’ll encounter the pain that we’ve mistakenly felt like we’ve left behind. We really did believe that all those whips and chains and rapes and exile and loss of language and cotton-picking and all that stuff...that we just left it behind and it’s better off left untouched, like Pandora’s box. Not realizing we are still dealing with the nonsense, and we’re never going to heal ourselves until we deal with it. We’re never going to come out and have new perspectives and treat each other differently, and be different people to each other, until we actually have that emotional catharsis when we begin to crack, until we begin to really have gratitude and humility and sincere gratefulness for not having had to have lived those lives. And also to live in a time when we have the opportunity to live better and do better by each other."

The ultimate generosity of Twitty’s book is that he has already done most of the work for his readers. All you have to do is be brave enough to crack the cover.

September 2018

Read the original article on Serious Eats.