A Complete—Tireless, Even!—Journey Into Silicon Valley's Tumultuous History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“The point of life and the meaning of freedom is to make something with what the world makes of you,” writes Malcolm Harris, a Palo Alto native, in his bracing new mega-history of northern California, Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World. Ever since Horace Greeley wrote those immortal words, “Go west, young man,” this storied region has been gilded by a mythos of advancement, invention, and reinvention. But according to Harris, that burnished narrative is far from the full—or true—story.

Billed as “the first comprehensive, global history of Silicon Valley,” Palo Alto lives up to its description, but it’s also so much more—in these whopping 720 pages, you’ll find nothing short of an exhaustive history of American capitalism. Harris deftly charts the long shadow of extraction in northern California, from settler colonialism to robber barons to counterculture capitalists. The rapacious greed of contemporary global capitalism, he argues, is an export from northern California, whose history and culture have concocted a noxious brew of capitalist exploitation, with human capital as the most valuable product. “It represents the gold rush and the next gold rush and the one after that,” Harris writes of his hometown, “from produce to real estate to radios to transistors to microchips to missiles to PCs to routers to browsers to web portals to iPods to gig platforms.”

As a massive wave of layoffs stokes fears that the bottom has fallen out of Big Tech, Harris takes a historical perspective. “The bloom falls off the rose every year, but that doesn't mean it's not coming back next year,” he tells Esquire. That’s global capitalism for you: it’s going to keep on keeping on. Ahead of Palo Alto’s release, Harris spoke with Esquire by phone. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: There’s a massive amount of research in this book. What did you learn that most challenged your preconceived notions about Palo Alto and its history?

MALCOLM HARRIS: There was so, so much. On a broad conceptual level, I was stunned by how short the Anglo-American history in California is. You're talking about just a few generations—not that many between the beginning of this colonial project and the current day. It's hard to think about that sometimes, because we write California as part of the national colonization story, even though it takes place under completely different historical circumstances. In terms of specifics, there was all sorts of history that I knew very little about. I didn't plan to write 30-plus pages about Herbert Hoover. Hoover being low-key the most important person of the 20th century was not something I was ready for, but that turned out to be the case, and I had to devote a bunch of the book to him. Early radical history in Palo Alto—I had no idea about any of that, and it was thrilling to read about the international communist anarchist association of Palo Alto.

$29.08

amazon.com

You coin a term in the book and refer to it often: The Palo Alto System. Can you break down what that means, and why it matters?

The Palo Alto System was a term that Charles Marvin and Leland Stanford, the original founder of the town, used to describe a unique way of bringing up, training, and commercializing the production of trotting horses. Previously, to breed, train, and sell trotting horses, you'd wait until they got older before you started racing them at a full sprint. Partly inspired by the early childhood education movement in Germany, they started sprinting horses as young as they could, and in doing so, they were able to operate the business much more profitably. They focused huge amounts of resources on colts that showed the most potential, even though they were young. In their mind, potential was a fixed quality that could be revealed. That project didn't transform the world of horses in the way they thought it would, but the ethos behind the Palo Alto System metaphorically underlies Palo Alto over the next 100-plus years. It's not literal—no one said, "We're going to apply the Palo Alto system to people and companies and the stock market." But they reflexively ended up doing it because they interacted with the same historical forces that Leland Stanford and Charles Marvin did, once upon a time.

Do we see people putting the Palo Alto system in use in other parts of the world?

We see it all the time, led by Silicon Valley. We see it happen when we look at potential rather than execution, when we bet on companies or people based on what we see as their speculative returns rather than their operating returns.

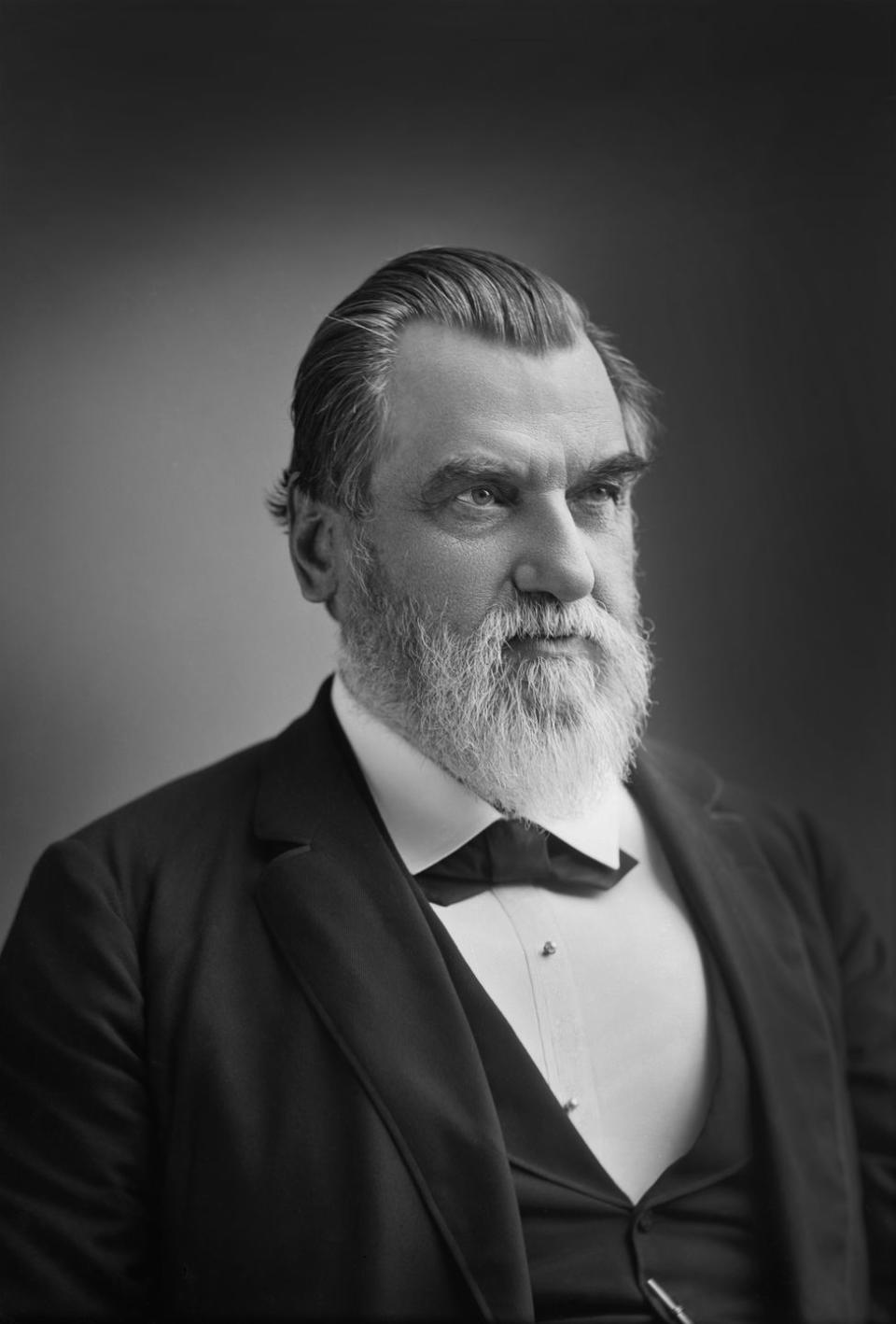

Writing about Leland Stanford and Collis Huntington, you say, “Neither of them laid anything but a symbolic track between California and the East. They hardly even enriched their shareholders. Instead, they had a good deal of money made for them. Such was the role of the Great Man under global Capitalism.” How has the role of the Great Man under Global Capitalism changed since the days of Stanford and Huntington?

It hasn't changed much. The shape of it has certainly changed—there's a big difference between Leland Stanford and Sam Bankman-Fried in terms of their style and presentation. But the role of spinning these big stories that could scale to the whole world, that can absorb infinite amounts of capital... that's still the same basic job. At the same time, on the reverse side, look at someone like Steve Jobs. The creativity and the imagination there is a cover for what Apple is actually doing, which is extending the development of capitalist production by pushing down wages and pushing production throughout the world. All of these historical forces that we end up interpreting as personality characteristics of these Great Men... when we look at them on a historical level, we can see how these impersonal forces operate through these characters. They characterize it—they give it human form. But we can understand it beyond them—not as a function of their individuality, but as this trans-individual thing.

I'm reminded of something else you write: "What interests me is not so much the personal qualities of the men and women in this history, but how capitalism has made use of them." I like that framing, and how it resists the cult of personality and celebrity around founders like Steve Jobs.

Steve Jobs’s personality is important—the fact that he is who he is ends up mattering. But what I want people to understand is that it matters because he fulfills a particular role. One way I try to get at that is through the chapter about Bank of America and the Giannini family. Amadeo Giannini had a classic child of immigrants success story; he founded the Bank of Italy, which turned into Bank of America. But I also tell the story of his father, who was the same sort of promising man, but he happened to get stabbed to death, and that was the end of him. He didn't end up doing it, so somebody else ended up doing it.

Other people will fulfill these roles. There's the development of a class system that's able to transmit these roles not through familial, aristocratic privilege, but through a bourgeois class. Leland Stanford Jr. died unexpectedly, but Herbert Hoover, an orphan, came to occupy his role instead. The privileges, wealth, and historical direction of the Stanfords could be passed down not just through their only child, who they happened to lose, but through the best representative of their class in the region—Herbert Hoover, who ended up being the best Leland Stanford Jr. they could ever hope for.

As you point out in the book, "Profits search for the necessary people, attitudes, and weapons to do what needs to be done, and profits find them."

Profit finds a way. It's an impersonal, accumulative drive that has characterized global society for this period of time. That's why it's such a good object to analyze, because it's coextensive historically with this world system.

There are so many breathless books and articles lauding tech founders. What would be a more responsible way to cover these Great Men under global capitalism?

I try my best to be deflationary and use some humor. It's important to show that there were other people in the story, too. The guy that we think of as the Silicon Valley founder is not the same as the Silicon Valley engineer who makes stuff. For every Steve Jobs, there's a Steve Wozniak. Steve Jobs didn't actually invent the iPod. We also need to see them in the context of the people who are creating the wealth on which they depend. I constantly try to show the workers as well as the capitalists, instead of just telling a capitalist history, or just telling history from below.

I really appreciated the chapter about the suicides at Foxconn, the Chinese Apple factory where over a dozen workers took their lives. That's as much the company's legacy as the iPod.

We think about Steve Wozniak wiring the first Apple, but then we don't talk about who wired the rest of the Apples, and who actually made the computers. We only care about the design of the first one, but not the execution. It's the execution that really made Apple the company it was at the beginning and has continued to be. It's only by looking at that relationship over time, between capital and labor, that you can get a realistic or true sense of these phenomena.

$29.34

amazon.com

You illuminate how Stanford University has its roots in eugenics. How should that shape how we think about and interact with the university today?

I think students might be really interested in this history, and the historical project that they're a part of and have been selected for. It's pretty explicitly a eugenic project and has been for a long time. How do we think about elite higher education in terms of its historical relation to eugenics and natural hierarchy? We need to pay a lot more attention to that, especially around the west. People have a tendency to separate California history from the rest of United States history, and be forgetful about California history. If you look at biographies of William Shockley, they all basically say, "We don't know where his racism came from. How could he be racist, growing up in northern California?" But he was born in the world's center for eugenic thinking. We don't associate that with California—we associate it with something else. But it's definitely California.

When I think about the state of Big Tech in 2023, it seems clear that the bloom has come off the rose. Amid a wave of mass layoffs, these jobs that once seemed so covetable no longer seem secure. As tech workers attempt to organize, management is fighting it tooth and nail. How do you make sense of this unstable moment for Big Tech?

The bloom falls off the rose every year, but that doesn't mean it's not coming back next year. These layoffs are totally cyclical. They're not shrinking the tech sector; it doesn't suggest that people now understand Silicon Valley is a scam, or that global capital is going to pull out and stop investing. In fact, it's never meant that. Y2K never meant that. The 2008 recession didn't mean that. It's never happened—there's been continually more investment in Silicon Valley as things have gotten harder for more people. I don't think this is a moment where tech has hit the end of the road or been confronted with its own core contradictions. You see that with all the so-called artificial intelligence nonsense that's going on right now, which is a pretty far-out version of Silicon Valley scamming. It's not that different from crypto in terms of how much there there is there, in my opinion. It's not over, because there's something inextricable about Palo Alto, Silicon Valley, and American capital.

Spoken like a true historian. Everyone is panicking and you're over here saying, "We've seen this before, and we'll see it again."

They're going to hire everybody back within a few months. It was just a demonstration of discipline for the markets. Even though tech companies saw their wealth explode and rich people got significantly richer during the pandemic, the labor situation was tight. Now that we've moved forward, this kind of crackdown is not unexpected. The other sectors are following tech's lead, which is a demonstration of the tech-ization of the total economy. The tech people who've been laid off don't have much to worry about. The job market, generally speaking, is pretty good. It's not like they won't be able to find jobs.

What can the history of Palo Alto tell us about the future of organized labor?

A lot, especially within the tech sector. We've seen this happen so many times before. What's happening now isn't the first organization of workers in Silicon Valley, although the kind of workers we see organizing might be different. We know that California capitalists have a tendency of real intolerance about labor organizing, going back to the turn of the 20th century and the axe handle brigades of the California Highway Patrol. We should expect companies to fight tooth and nail, especially in the tech sector. There's a set of strategies they've used over the last 150 years that we can really learn from.

In the book’s final chapter, you propose that Stanford University return its land and wealth to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. Some critics have pushed back at the idea, with one trade writing that your plan “probably doesn’t stand a chance.” What’s your response to those who call your proposal is too audacious or too unlikely?

I think it's kind of funny. I think it's very easy to make an extremely pragmatic case for, if not turning over the entire 8000 acres and $30 billion Stanford endowment, then at least transferring enough land and money to live on back to the ancestral Muwekma Ohlone community. Stanford acknowledges them as the ancestral title owners of the land. It's about 500 people in a politically recognized group. Stanford can afford to give them enough land to live on in their ancestral territory pretty easily, especially at a time when housing costs in the Bay Area are driving the few Muwekma Ohlone out of the area where they still have ancestral claim. It would be a huge step for the United States—and the biggest thing Stanford could do since the founding of Stanford. It wouldn't cost much of anything in particular; it wouldn't violate anyone's property rights. It's just a college board of trustees, and college boards of trustees do crazy left-wing stuff all the time. That's what we're told, anyway.

People think it's a lot of land, but in the history of the colonization of California, it's the tiniest, itsy-bitsiest piece. It's a nice itsy-bitsy piece, but should we give back not-nice pieces of land? For people to treat the proposal like it's ridiculous speaks to ignorance. If you go to the Stanford website where they state the land recognition, they have a link to the concept of LAND BACK. It seems very easy to me, on some level, but the fact that it's unthinkable to other people speaks to the impersonal rigidity of the capitalist system. You're not able to make decisions like that. Decision-makers are not permitted to make even, what in this larger sense, is a very small decision. It's too big a threat to the system. And if that's the case, that tells us something important.

You Might Also Like