When it Comes to Ticks, Lyme Disease is Only the Beginning

ONE NIGHT in the late 1990s, Greg Gilbert, Ph.D., discovered he was allergic to meat. A forest ecologist and professor at UC Santa Cruz, he was working with the indigenous Guna people on the Caribbean coast of Panama to diagnose a disease in coconuts. At dinner, his host served him a stew made out of peccary, a hairy relative of the pig. Gilbert got violently ill and assumed he’d eaten something that either was unsanitary or had gone bad. The next time he visited the Guna and ate pig’s-feet soup, it happened again. That’s when he realized he hadn’t had a one-off reaction. He suffered an allergic response every time he ate meat.

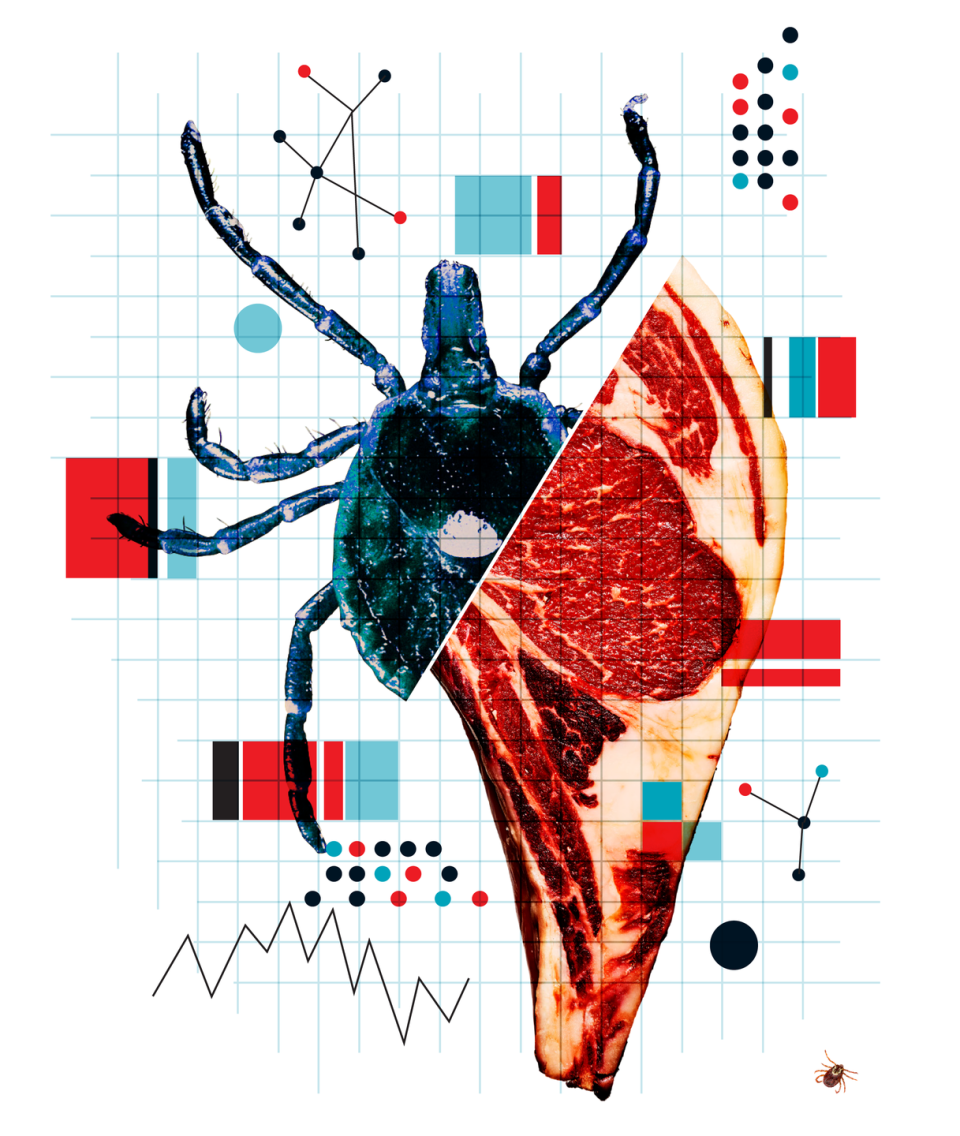

Fast-forward a decade: Gilbert was still allergic, and just one of many people who suddenly and inexplicably found themselves having a reaction to beef, lamb, pork, and venison. A coworker he’d been in Panama with who’d experienced similar symptoms connected him with a chain of scientists. It eventually led him to researchers at the University of Virginia who had been studying a vicious allergy to a new cancer drug. People seemed to be allergic to a sugar that was introduced to the drug via the mouse cells used to produce it. That same sugar, called alpha-gal (short for galactose-alpha-1,3- galactose), appears naturally in meat—the kind of meat Gilbert ate and that his colleagues and many guys in America might eat every day. But the scientists couldn’t figure out how anyone—neither the cancer patients nor other people who were getting sick after eating meat—had developed the allergy in the first place.

On a hunch, lab member Scott Commins, M.D., Ph.D., started asking people with these allergies how much time they spent outdoors. Many said they were gardeners, hunters, hikers— and “all reported a history of tick bites,” he says. Gilbert was in the same situation. To study tropical ecosystems, Gilbert often spent part of the year on Barro Colorado Island (BCI), a verdant wilderness in the middle of a man-made lake in Panama that is home to 15 to 20 species of ticks in frightening density: There are some 8,500 individual bloodsuckers per 300 square meters. When researchers tramp through the forest, they often brush against “tick bombs”—clusters of juvenile seed ticks that emerge in such volume that it would be impossible to remove them from clothing one at a time. Field researchers, like Gilbert, usually carry a roll of masking tape: They rip off a piece and use it like a tick lint roller.

When Gilbert, along with three of his colleagues from BCI, got their blood tested, not only were they positive for an allergy to alpha-gal, but two of them showed the highest reactions the lab had ever recorded. There was something in tick saliva, the UVA scientists determined, that was spurring an allergy to alpha-gal, and to meat. Like ticks themselves, the allergy was spreading everywhere.

AMERICA HAS a problem with tick- borne diseases. It’s no BCI in its density and variety of ticks, but from 2004 to 2016, tick-borne illnesses more than doubled in the U. S., and that doesn’t even include alpha-gal allergy, which was discovered during that period and wouldn’t count toward that total, anyway, because it’s an allergy and not an infection. Seven new tick-borne viruses, bacteria, and parasites that can cause illness have been identified in the past two decades, a time when the tick population itself has exploded.

But while most Americans have heard of—and fear—Lyme disease, other tick- borne maladies haven’t gotten nearly as much attention: Untreated ehrlichiosis can land people in the hospital. The parasite Babesia can destroy your red blood cells. Rocky Mountain spotted fever can cause fatal organ damage. And alpha- gal may be responsible for increased immune reactions—the body’s response to an allergen—in 10 percent of the population in some parts of America.

It doesn’t always manifest as a call-911, full-bore physical house fire. It can appear as unexplained stomach upset, diarrhea, rashes, joint pain, or itching. “There’s no doubt that some people have the alpha-gal allergy and are poisoning themselves unknowingly by eating meat,” says Dr.Commins.

Different types of ticks transmit different illnesses, but many people don’t know that or don’t think to take a picture of their assailant to help them sort out a diagnosis. With alpha-gal/meat allergies, researchers know that one of the primary methods of spread is the lone star tick. There’s been a surge in the lone star tick population in the past few decades thanks to climate change, rising deer populations, and reforestation. They’re especially prevalent in the southeastern and eastern U. S. but are spreading to the midwest and northeast, and they are most active in late spring and summer. Which is, er, right about now.

THE CENTERS for Disease Control is monitoring the rise of tick-borne problems. In a 2018 Vital Signs report, it warned that the United States is not adequately prepared to control and prevent infections caused by ticks. David H. Walker, M.D., cochair of the Department of Health and Human Services’ tick-borne-disease working group, says the group’s mandate has expanded from its first set of meetings to the latest. “The first report in 2018 focused on Lyme disease,” he says.“Now we are working on all the tick-borne diseases in the United States.”

At the University of Rhode Island, public-health entomologist Thomas Mather, Ph.D., is searching for an anti-tick vaccine that would target a number of tick-transmitted infections rather than addressing each individual ailment. “The idea is to make the bite site inhospitable to any germ the tick might transmit, preventing the germ from infecting the host,” he says.

Unfortunately, it’s still far from a public rollout, and because alpha-gal sensitivity is created through a different mechanism, it may not do much for meat allergies even if it works.

Your smartest strategy remains bite prevention.

If you’ve been bitten by a lone star tick, be particularly vigilant for symptoms that begin after you eat meat. An alpha-gal allergy can take several weeks to develop, and symptoms often do not appear for a few hours after the offending meal has been consumed. Tracking your diet can be helpful. For example: Fattier cuts of meat seem to cause more extreme reactions. If symptoms appear, ask your doctor or an allergy specialist for a blood test for allergic antibodies to alpha-gal. You may have to stop eating meats that come from most mammals, and even, in extreme cases, milk, butter, and ice cream. Yeah, rough. But there is some positive news: Most tick-borne illnesses are treatable. And many people with an alpha-gal allergy who manage not to get bitten again recover their ability to tolerate meat. “In many cases, we don’t find this is a lifelong immune response,” says Dr. Commins. “It may go away after 18 to 36 months. When appropriate, we begin to reintroduce meat.” Why the sensitivity decreases remains a mystery.

You Might Also Like