Is a College Education Even Worth It Anymore?

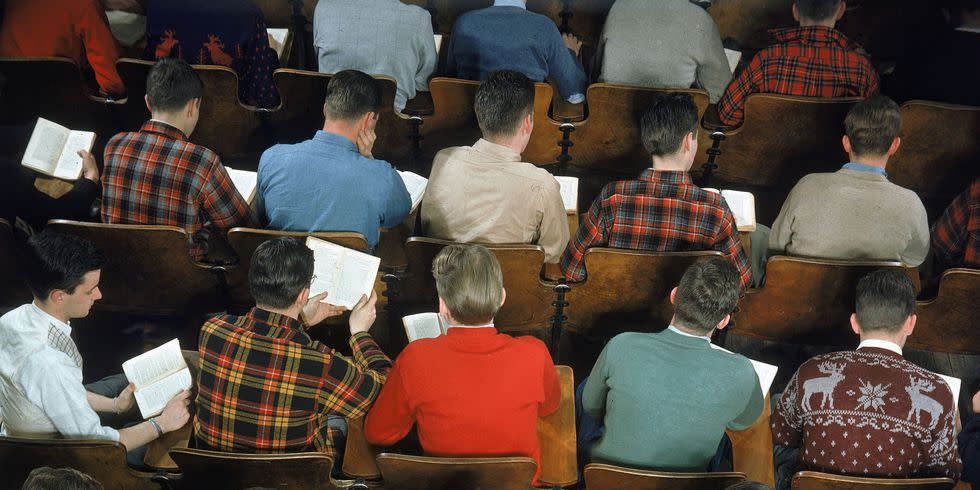

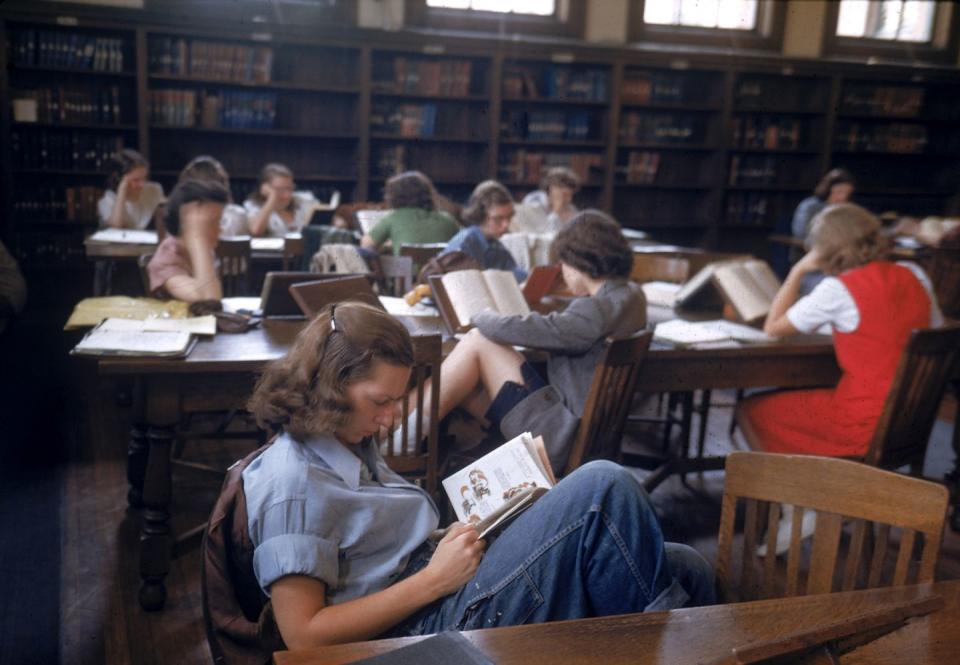

Half a century ago, when I was in college, you had a choice. You could either hang out at Lamont Library (no women allowed), shoulders hunched, Marlboro in hand, poring over John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, or you could dodge tear gas canisters as a platoon of shield-wielding police barged into Harvard Yard to drag demonstrators against the Vietnam War out of University Hall.

Always greedy for experience, I chose both.

Today there are different causes; I’m not sure about the library part. I get the sense that reading old books (or new, for that matter) has become an obsolete pastime on campus, akin to playing the lute. Yet college tuition, which was steep enough in 1968 that my father had to raid his retirement fund to pay it, has become insane. It now costs $72,428 to attend Claremont, California’s Harvey Mudd College, the most expensive in America, for one year. Oberlin will set you back $71,439.

And what do you get for this stupefying sum besides an unwelcome case of academic sticker shock?

Today’s recent college graduates won’t break even until the age of 31, according to a report issued by Goldman Sachs-and that’s if they make a beeline for Wall Street, without any detours to Teach for America, I presume. As for the long-haired (or now man-bunned) English majors, they'll get their money back when the sun is dismantled and the stars are put out (phrase adapted from W.H. Auden, in case your knowledge of poetry has gotten rusty).

"Graduates studying lower-paying majors such as arts, education, and psychology face the highest risk of negative return," writes the bottom line-fixated scribe at Goldman Sachs. "For them, college may increasingly not be worth it."

This weeding out of vocational and low-earning students has consequences. Who is going to pay the tuition and fill the dorms? Also, it’s not great for diversity. American colleges have become finishing schools for the aspirant rich. We might as well turn the walkways on campus into bridal paths.

Do you want to hear a depressing statistic? Thirty-one percent of the Harvard class of 2014 ended up on Wall Street; 70 percent of the class applied for jobs in consulting or finance. Only 8.8 percent went into public service. Who can blame students for making this choice? We have increasingly become a culture that equates wealth with prestige. Money talks in a louder voice than it has at any time since the Gilded Age. The lack of it is not only pitied, it’s stigmatized.

But if you’re not in it for the money‚ maybe it does make sense to give college a skip. Why knock yourself out going to class when you can sit in front of your laptop and attend a MOOC-Massive Open Online Course-taught by a distinguished professor but at a fraction of the cost?

The action these days is elsewhere: in the sun-filled atriums of Google and Facebook, stocked with ping-pong tables and state-of-the-art treadmills. And, anyway, the lack of a degree is no impediment to making the Forbes 400 list. Look at Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates.

We have entered a new Age of Utilitarianism. "Human beings have trouble retaining knowledge they rarely use," Bryan Caplan, a professor of economics at George Mason University, wrote in the Atlantic recently. Why read a book if you’re going to forget everything in it? Why take a course in the 19th-century French novel when it offers such a feeble rate of return? Why loot your parents’ nest egg or take out a government loan to pay for your tuition? In short, why not just go get a job?

The problem with logical arguments, I find, is that they often ignore an illogical truth. David Foster Wallace, in a canonical commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005, made one of the most passionate assertions of the importance of learning for its own sake that I’ve ever read.

For Wallace it was the lack of utility that gives education its value. Study makes us think; it reminds us that "the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self." Why so-called? Because there are other real worlds out there, worlds that open themselves to us in the Policraticus and Madame Bovary, useless classics you can’t monetize. They require our attention, too. "I loaf and invite my soul," wrote Whitman-to observe, to contemplate, to remember.

Is this an activity worth encouraging? Does a four-year stint at a citadel of higher learning teach us to think, rather than just to get and spend? Does it inculcate moral values? Maybe Bryan Caplan is right and it is "a big waste of time and money."

But so what? It sounds good to me.

This story appears in the August 2018 issue of Town & Country.

Subscribe Now

You Might Also Like