College Cheating: Is a BA Worth Anything If It’s All BS?

Scott Limmer has been a defense attorney in Nassau County for nearly a quarter of a century. Solidly built, with salt-and-pepper hair and a booming Long Island accent, Limmer is the kind of guy who can make anyone feel comfortable, including the criminal defendants who are the bread and butter of his practice. Or at least they used to be.

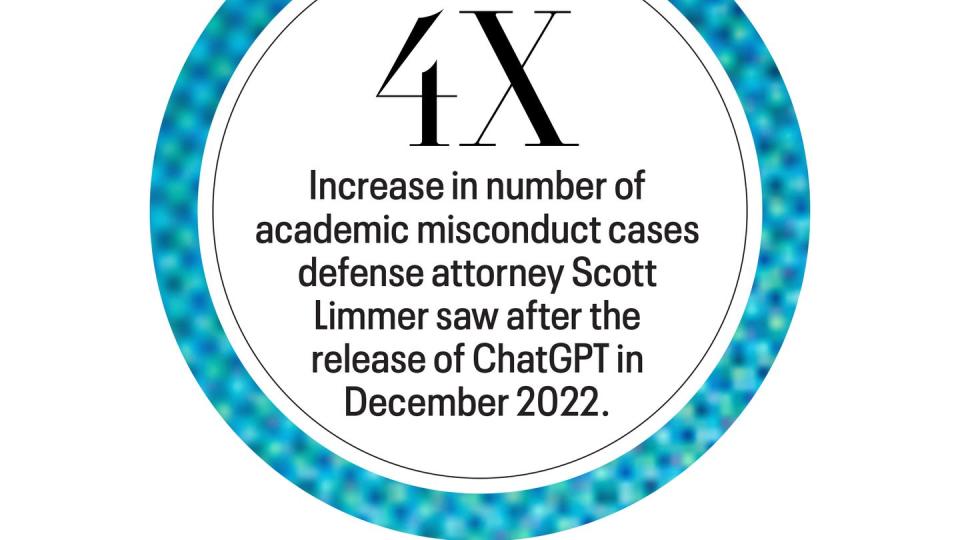

Lately, college and university academic misconduct cases, wherein a student is accused of cheating, plagiarizing, or fabricating schoolwork, have become a much larger portion of his caseload. The initial spike happened during Covid, when online learning caused a dramatic rise in academic dishonesty at colleges across the country. “A lot of students took advantage of doing things at home,” Limmer says. “There were text groups between 30 and 60 students while they were taking a test. Just wild stuff.”

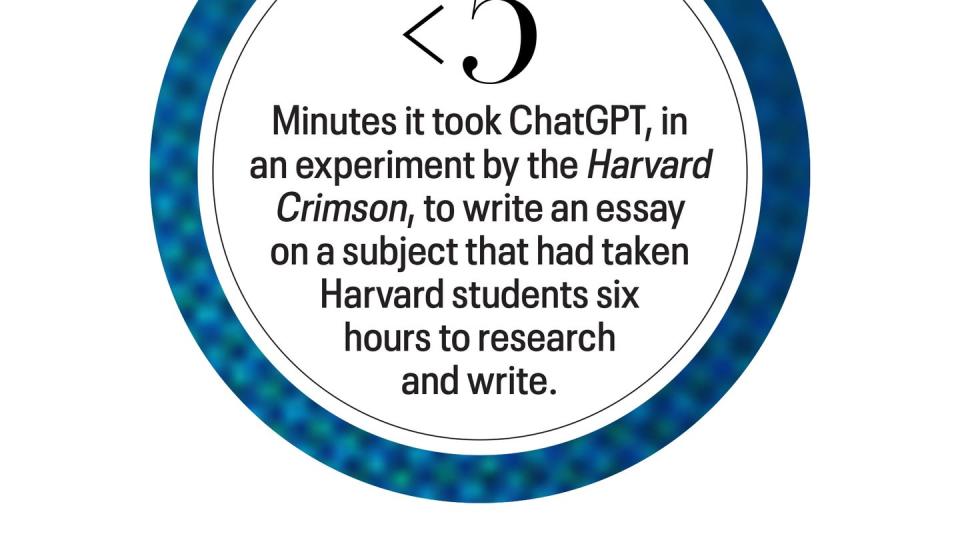

Then last November the equivalent of an atomic bomb dropped on higher education and its offices of academic integrity: ChatGPT. Suddenly plagiarizing from an old student’s term paper seemed positively quaint. Now students were able to type in prompts and watch ChatGPT and other AI chatbots spit out, say, an essay on the Christian allegories and allusions in Hamlet, or a complex sequence of coding. Unlike in traditional forms of cheating, there was no means of verifying that the work was original, as was possible with platforms like TurnItIn, which check papers against a database of hundreds of millions of archived student papers, journals, books, and websites.

And so the fallout began. Last May a professor at Texas A&M flunked a class of seniors, claiming that they had used ChatGPT on their final papers, only to later admit he had been wrong (the students were exonerated). Timothy Main, a writing professor at Conestoga College in Canada, wrote on social media that he has “caught dozens” of ChatGPT-generated writing assignments. “We’re in full-on crisis mode.”

For the past several months universities have been scrambling to adjust to the new reality, making revisions to their academic integrity policies to address what defines plagiarism with AI. Professors, meanwhile, have been overhauling courses, incorporating more handwritten assignments and oral exams. Some are coming up with innovative ways to allow students to use the new technology in thoughtful ways, such as using AI to create a written essay and then having the students critique it for biases and false information.

Universities are “playing a game of Whac-A-Mole,” says Naomi R. Shatz, a partner at Zalkind Duncan & Bernstein in Boston who works on academic misconduct cases. “They were trying to figure out how to address one kind of plagiarism—people searching things on the internet and copying them—and a product like TurnItIn appeared to help them. And then all of a sudden there are new and different ways that students can engage in academic misconduct, like using AI, so they’re going to have to figure out how to deal with that.

“It does feel, from the outside, not being a professor or a student, that they’re constantly in this race to try to outsmart each other.”

They’re also in a race to protect themselves. And for students accused of cheating this increasingly means calling attorneys to help them navigate a landscape that is both wildly new and in flux. “I’ve never been involved with something in the legal world that’s in such a state of upheaval. It’s like the eye of the hurricane,” says Limmer, who says his academic misconduct cases quadrupled last semester because of AI. Indeed, the huge gray area inherent in AI cheating cases (What if some but not all of a paper is written by AI? And how can that be proven?) has added a new complexity to integrity processes at schools, which are already incredibly confusing to students and families. Because academic misconduct cases are not regulated by federal law, how conflicts are handled can vary dramatically, not to mention that misconduct policies differ from school to school. One case might be resolved simply by a student having a conversation with a professor. Another might drag on for months and involve a disciplinary hearing through a school’s office of academic integrity. And yet the repercussions can be grave.

“There’s nothing that affects your future more than having a mark on your transcript saying you were suspended for a period of time or expelled,” says Limmer. “Schools can say whatever they want: It’s a legal proceeding! You’re using a legal standard to prove somebody responsible.”

Despite the advantage lawyers can provide, most families aren’t even aware that they work in this arena, and their cost keeps them out of reach of those who may need them the most: students from less advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds who don’t have access to networks or other resources to help them stand up to a school’s charge. Fees run from about $5,000 for basic advising to $30,000 for working with a student through a monthslong conflict with a college or university. “It’s not cheap,” Shatz says. “So it’s absolutely true that only students with resources, which usually means parents who can pay for a lawyer, get the benefit of a lawyer. That is an unfairness that exists in this area.”

The benefits, though, are substantial. Although attorneys are generally not permitted to be present in any meetings or hearings at a school—because misconduct cases are handled outside the court system—they operate like sideline coaches-slash-psychologists, providing advice to students on what to say in hearings and helping them craft written statements. They also recover evidence, find witnesses, and review the minutiae of a college’s code of conduct to determine if the allegation is truly a violation. In some cases they even hire private investigators to help students build their cases. For example, they might seek phone logs or other evidence that supports the student’s alibi, like an E-ZPass photo from the George Washington Bridge that proves the student was driving on the night he was accused of stealing a test from a professor’s desk.

Felice Duffy, a former federal prosecutor based in New Haven, Connecticut, who now runs a private law practice that specializes in Title IX and academic code cases, says that when lawyers get involved, they are expected by school administrators to be “a potted plant.”

“But I’m never a potted plant, because I work at this as a facilitator,” Duffy says. “At most schools the standard is preponderance of evidence. And that can literally mean, do you believe the professor or the kid? You can already see the uneven dynamic there. If a student says, ‘I didn’t do that!’ and a professor says, ‘I think you did,’ that’s enough—without any other evidence. It doesn’t always happen that way, but that’s preponderance: if you believe one over the other.”

Shatz says that hiring a lawyer sometimes is just about getting students to slow down and not sabotage themselves by launching into emotional denial mode when first approached with an allegation. “Where students often get tripped up is by denying things initially,” she says. Ideally, students should “not respond immediately to the professor with the first thing that comes into their heads, but talk to their parents, talk to a lawyer, get some advice on how to approach it and have a minute to step back and say, ‘Okay, what am I being accused of? Did it happen? How did it happen? What can I say about it?’

“For a lot of students, this is the first time they’re dealing with something like this. They are adults under the law, but they’re doing a lot of things for the first time, and getting advice from parents or a lawyer could be helpful.”

Lawyers argue that they can also bring more structure to a process that Duffy says is “all over the map.”

“I like Title IX cases,” she says, referring to sexual misconduct, harassment, and assault cases. “They’re hard, but there are so many protections for both sides.” (Attorneys are permitted to be present with their clients in these cases.) “So I know there’s a shot at fairness. But the student misconduct ones, like cheating…”

“Every policy is different. Every process is different,” she continues. “Sometimes the student walks in, talks to the dean, the dean makes the decision. No oversight, no appeal. Sometimes the student walks in, talks to the professor, there’s a big investigation—a good one. A student might go to a hearing with a panel of people, the accused gets to respond to everything, they get to make opening and closing statements. It can be this three-month, four-month, stressful thing, where their friends are involved, picking sides, saying, ‘I don’t want to be a witness in this.’ And some can be a one-day thing where they’re like, ‘Sorry, you’re expelled.’ Some say, ‘Zero tolerance. Bye-bye!’ It doesn’t even matter, they don’t care what your reason is.”

Tricia Bertram Gallant, director of the academic integrity office at the University of California San Diego, maintains that universities work hard to ensure a thoughtful process when cheating is alleged. “Although the systems we run at universities are not legal systems, we try to honor the spirit of the legal system in America, which is that everyone is innocent until proven guilty,” she says. “If we’re going to impose any kind of disciplinary sanction, whether it’s a warning or probation or suspension, there has to be some due process. Due process naturally means process, which means time. And effort.”

She continues, “It takes longer to allege cheating than it does to ignore cheating. I’ve been saying that for a long time. And, frankly, it should.”

Indeed, if lawyers feel that cases are sometimes handled too abruptly, professors often feel just the opposite. After all, the work of reporting and following up on a cheating allegation falls hardest on faculty members, many of whom are still drained in the aftermath of the pandemic, when they were tasked with redesigning curricula for Zoom and dealing with a surge in cheating cases.

UCLA professor Jean-Luc Margot recalls teaching a general education course on astrobiology in 2020, when classes at UCLA were remote. During a two-hour, open book, multiple choice exam that students could take anytime during a 72-hour period, he detected that a dozen students had cheated. “It was an all-time record for the course,” he says.

Many of the students admitted to dishonesty, but “one group of students hired lawyers, who in turn hired or claimed to hire statisticians. The lawyers demanded extensive records in an attempt to show that the correlations (on the test) were due to chance and did not involve unauthorized collaboration among students.”

In the end, all but one student admitted to cheating. That student’s case was referred to the student conduct committee, which found the student guilty of academic dishonesty. “Resolution took approximately two years and involved dozens of emails, several conversations with the UCLA Office of the Dean of Students, and hearings of the student conduct committee,” Margot says. “Reporting a suspected academic integrity violation is not for the faint of heart.”

Bertram Gallant says she “sympathizes with faculty, especially if you think about an adjunct faculty member who maybe is a freeway flyer who works at four different institutions. They don’t get paid to do that, to see a case from fall semester through until spring semester. So there are some issues there. But I don’t think we can simplify it to say the process is just too long to be bothered with.”

As the fall semester was gliding into gear, AI was taking center stage in academic integrity offices at campuses around the country. Anna Mills is a writing teacher at Cañada College in Redwood City, California, who is on a joint task force of the Modern Language Association and the Conference on College Composition and Communication to develop resources and professional standards around the use of AI and writing. Mills says she has “spoken with administrators who have said, frankly, that they’ve had to let cases go even if something was flagged as AI text. If the student says, ‘No, it’s not AI,’ they really hit a wall. They can’t prove it. They can’t punish the student. So we are really in a bind.”

In September Mills experienced an AI conundrum herself, writing on X (formerly Twitter): “A student told me he used ChatGPT to help him write an essay. (My policy didn’t allow it, but he seemed not to realize he had gone against the policy.) And he seemed really excited about the ChatGPT prose. He seemed proud that he had changed it and, in his mind, made it his own.”

Some professors are resorting to AI checkers, such as one released by TurnItIn last spring, which produces a report stating whether a paper was written by AI and, if so, what percentage of the paper. TurnItIn has acknowledged there have been false positive reports and is working to improve the platform, a loophole that lawyers are digging into.

“I’ve had a number of cases where it’s come out that this checker says it’s not written by AI but the professor believes a small percentage is AI material,” Limmer says. “So my question to the school is, can you please provide me with the methodology that the AI checker uses so we know where it’s coming from? Because the paper is not being copied from something. It’s almost like a human being created it.

“Granted,” he says, “it’s soulless.”

This story appears in the November 2023 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like