'Cockeyed Happy' Offers a Look Inside Ernest Hemingway's Summers in Wyoming

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When you think of places iconically associated with Ernest Hemingway, chances are you think of Key West, Havana, or Paris. Wyoming likely doesn't rank high on the list, but that may be about to change. In Cockeyed Happy: Ernest Hemingway's Wyoming Summers With Pauline, Mountain Living editor-in-chief Darla Worden takes us inside the little-known details of the six summers Hemingway spent in Wyoming between 1928 and 1939. These were adventuresome times for the then-ascendant writer, an avid outdoorsman who reveled in hunting, fishing, and horseback riding through the spectacular landscapes. They were also extremely productive times, as the anonymity of rural Wyoming allowed Hemingway to work uninterrupted on such masterpieces as A Farewell to Arms and Death in the Afternoon. In a letter from his lodgings at a local ranch, Hemingway wrote, “This is a good place and not getting mail is a hell of a fine thing and very good for working."

For all its high-spirited anecdotes of the game Hemingway hunted and the cars he crashed, Cockeyed Happy is also the slow burning story of a doomed marriage. In 1928, following the celebrity-making success of The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway fled Paris on a cloud of scandal: recently wed to his mistress, Vogue editor Pauline Pfeiffer, Hemingway was facing censure from those who felt he'd abandoned his first wife, Hadley Richardson, and their young son, affectionately known as Bumby. Back in the States, while Pfeiffer recovered from the birth of their first son, Hemingway escaped to Wyoming, fell in love with the landscape, and brought Pfeiffer along for subsequent getaways. During those six summers, the cracks in their marriage would widen into chasms. Pfeiffer gave up everything to be with Hemingway—her journalism career, her friends, her Catholic convictions—and in the end, lost everything when Hemingway left her for Martha Gellhorn.

“Wyoming was the blank page just waiting for him to put his mark on it," Worden writes in Cockeyed Happy. Today, Hemingway's presence is still felt in parts of Wyoming, while the revelation of new details about his time there promises to give way to a deluge of unheard stories. Worden spoke with Esquire from her native Wyoming to discuss Hemingway's "mountain man" persona, his faults as a husband, and his lasting legacy in the Wyoming region.

Esquire: You describe Cockeyed Happy as creative nonfiction, writing in your author's note, “Creative nonfiction, a term some feel is confusing, means telling a nonfiction story using such common fiction tools as scene and dialogue.” How did you come to this particular narrative approach, and calibrate what it should feel and sound like?

Darla Worden: It took a lot of effort, to tell you the truth. I can’t even tell you how many times I started this book. I started with the traditional narrative form, opening with Hemingway coming to Wyoming, and it was really boring. It just bored me to tears. I thought, "This just doesn't seem like the right way to tell it." I was proceeding down that path when I was invited to read from my work in progress at the Sheridan Inn several summers ago. I read from the first chapter, which was different than what you have now, but it was about Hemingway coming to Wyoming and going up Red Grade Road. After the reading, a woman came up to me and said, " I'm so glad you didn't write about Pauline, because no one liked Pauline."

That sparked my thinking. I realized I hadn’t read much at all about Pauline. There was one really wonderful book—a straight biography written by Ruth Hawkins. When I started reading the letters between Pauline and Hemingway, I thought, "Pauline's voice hasn't been represented in this whole relationship, so I need to add her." That’s when the book took this different course.

ESQ: Hemingway is a writer very rooted in place. He’s iconically associated with so many places: Key West, Havana, and Paris, just to name a few. In this book, you add Wyoming to that cartography. He spent a lot of summers there, but it's not part of the lore of Hemingway, like these other corners of the world. Why do you think his time in Wyoming is less known or less celebrated?

DW: I can't say for certain, but I know he once made a comment that he wanted to write about the ranch, but he wasn't ready. In For Whom the Bell Tolls, he mentions this area of Wyoming on the Montana border. He starts in Sheridan and then he goes to the Nordquist Ranch, which was closer to Yellowstone. In the letters from his final days, when he was coming unglued, he wrote, “I wish I could be at the ranch.” I think it was a special place to him that he was maybe going to write about, but he never did. He protected it.

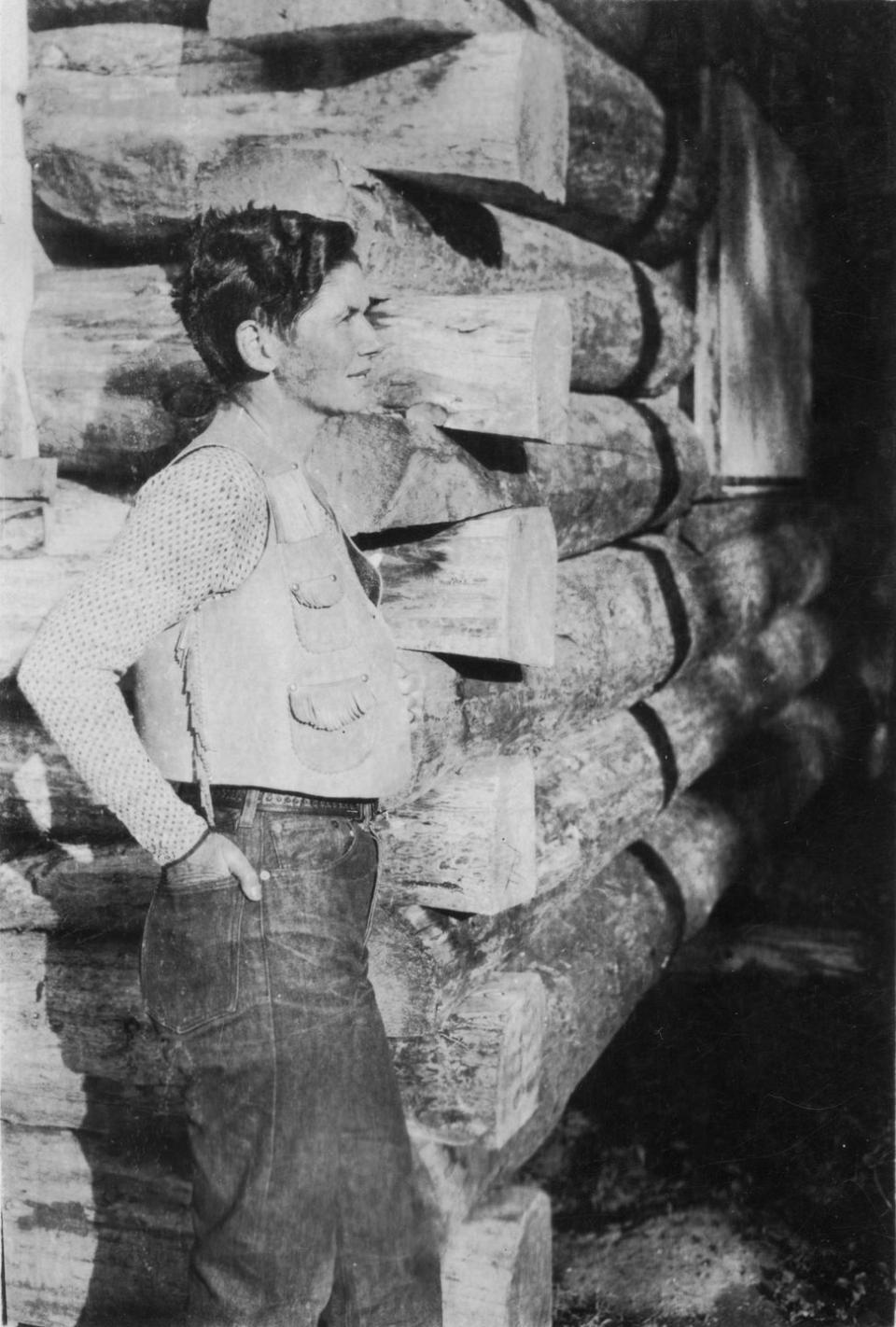

ESQ: You write, "Ernest liked to have an audience when he played mountain man." Hemingway did so much hunting, fishing, and riding in Wyoming. How much of that was a performance for the captive audience he brought there?

DW: I think it was both. He was a thrill-seeker, so he loved it. At one point, he decided to hunt down a grizzly bear. He was just fearless, and actually pretty reckless. I only touched on some of the accidents he had out in Wyoming—there are many more. I was fascinated to learn about how upset he was by the publicity about himself. He wanted to control the publicity, and he didn't want people writing about his personal life, so he crafted a persona to present to the world. Then I think he started believing the persona, and he really became that mountain man. Some of the things about Hemingway, you just couldn't make up. I didn’t need to write a work of fiction; he's the perfect character, because he's so complex that you don't have to make anything up. He’s great for nonfiction because you can write about his fascinating life as it was.

ESQ: You reference a letter Hemingway wrote about drafting at the ranch, in which he claimed to have drank nearly a gallon of wine and a half gallon of beer in one sitting. During his summers in the west, were there signs of the alcoholism that would later shape his life?

DW: That fact came from a letter that he wrote, so we have to take his world for it. Is he bragging? Did he exaggerate? After drinking, he would have gastric remorse, as he called his hangovers. Despite the fact that he drank heavily, that guy worked every day. His hard work shines through. In the recent Ken Burns documentary, something struck me about his physical state. After those two plane crashes, it took him a long time before he could write again. He couldn't concentrate, and he’d had all those accidents. He was in a car crash later in life when his son was driving, and he got a concussion. Once, a skylight came down on his head. He drank a lot in his lifetime, but in his final days, he couldn't drink. He was on a strict diet. I wonder if some of the madness at the end of his life came from these other injuries, in addition to years of abusing alcohol. I’m not a doctor, but I wonder if the combination drove him to take his life. He took a lot of hits to the head, and then, to have shock therapy… People think he killed himself because he was an alcoholic, but I think it was a lot more complicated than that.

ESQ: What kept Hemingway coming back to Wyoming all those summers? He could have traveled anywhere in the world, so what was the allure of Wyoming?

DW: I think he loved being anonymous, because he was two people. He loved being the center of attention in certain settings, but he also loved being anonymous. That's why he loved Sheridan. He felt like it was too settled, so he found the Nordquist Ranch, a remote place near Yellowstone, and no one knew him there. He could be mountain man. He loved hanging out with the guys in the Wranglers. I think the other thing that kept him coming back every year was the cool weather, because he couldn't write in heat. Key West would get so stifling, and so did Havana. He would say, "I've got to get out of here. I can't write in this heat." He loved the cool mountain breeze.

ESQ: You delineate sections of the book with lists of qualities Hemingway loved about Pauline, and with each new section, some of those qualities are crossed out. How did you come by that list, and that decision?

CW: I was thinking about love, and how when we fall in love, we have all of these qualities we love about someone. They say, "At the end, the qualities you fell in love with are often the qualities that drive you mad." I would read in their letters, where a lot of this material came from. He loved that she never got sick, but then a few years later, she's getting sick all the time, and that bugs him. At the beginning, it was a passionate, torrid affair, but eventually, they couldn’t be spontaneous. They had to really plan their sex for medical reasons. In the end, even after they divorced, he said that was part of why he couldn't stand to be married to her anymore. I plucked those statements from their conversations. I thought it showed the deterioration of what once was a mad love affair to a really adversarial situation.

ESQ: You call Pauline “the invisible wife.” What exactly made her invisible?

DW: Hadley was the hero. Everyone loved Hadley. Hadley was the beloved wife, and deservedly so. As the story goes, Pauline was Hadley’s friend, and Pauline stole Hemingway. A lot of their friends in Paris abandoned Hemingway during that time for leaving Hadley and their son, Bumby. Hadley and Pauline patched things up—that, to me, is the real testament to their character. If Pauline was really wretched, she could have taken Hemingway and cut off ties with Bumby, but she did the opposite. She loved Bumby. She invited him. She took care of him. In my view, people have written her off as a husband stealer without giving her the credit of what she actually was, which is a woman who fell madly in love with a dynamic, charismatic man. She was the only editor he wanted to edit his work, even after they broke up. She was so important, but she hasn’t received her due.

ESQ: You write, "Pauline had signed up for a marriage where Ernest's needs came first, and he expected her to be with him. There were times she had to choose between being a mother or a wife." That struck me as so deeply sad, and such an impossible choice. We see Pauline learning to hunt, fish, and ride to appease Hemingway. We see her climbing stairs to get her pre-pregnancy figure back for fear that he’ll leave her. It all seems like living in service to her husband. What toll did that take on her?

DW: I didn't want to end the book on a horribly tragic note. I tried to leave it ambiguous, but the truth is very tragic. She realized after they divorced that she had forfeited her career, her friends, and her relationship with her sons. She left them for months at a time because Ernest believed that others could raise their children just as well as they could. Others could feed them and tuck them in, so leaving them shouldn’t be a problem. Until her dying day, she worked to be a good mother, but so much was lost.

When they went to Africa and left the boys for months on end, one of their friends brought a photo of the boys for Pauline. Pauline said, "Oh, the poor little lambs. They miss their mother.” Hemingway made it clear that he always had to come first, or he could find someone else. She was really tugged in both directions.

ESQ: We see quite a bit of Hemingway as a father in this book—his charms, but also his limitations. How would you describe what kind of father he was?

DW: When you read a comment like, "Other people can raise your children just as well as you can,” you make some preconceived notions. His sons had issues with him, but they also really loved him. I think he was a complicated father, because he could be so demanding and harsh, but there were tender moments. Once when his son Patrick was very ill, he sat outside his door and wouldn’t leave.

ESQ: You write, "During Pauline's years with Ernest, he'd gone from an unknown writer to the great writer of his time." This is true of all of Hemingway’s wives, to some extent, but in the case of Pauline, how did she make his career and his success possible?

DW: The first thing that comes to mind is her money. She definitely financed the Hemingway lifestyle and persona. She came from an affluent family, and he liked that, at first. Her Uncle Gus was always writing checks for them, enabling their international lifestyle. To go on safari was extremely expensive. Hemingway was always money-conscious; in his letters, there are so many details about owing a friend money, or a friend owed him money, or Pauline spent too much money at the couture designers in Paris.

At the time they got together, he wanted to switch publishers. He had signed up with Boni and Liveright; Sherwood Anderson was also an author with them, who had helped Hemingway as a young writer. Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald and wanted to switch to Fitzgerald’s publisher, Scribner. To escape his contract with Boni and Livewright, he came up with an idea to write a satirical novel making fun of Sherwood Anderson. It was called The Torrents of Spring, and it was cruel. Hadley was against it, but Pauline was for it. She was unquestioningly supportive of him, and was a talented editor of his work. If editors dared to criticize him or suggest anything, he would write them off, but he trusted and accepted her edits. Ultimately, her money allowed them to live this lifestyle that created the persona. She also edited his work, typed his work, and supported whatever he wanted to do.

ESQ: That’s fascinating. All these decades later, the persona is as much a part of what keeps his legend alive as the work. For her to have been the unseen hand behind that is huge—and returns us to your point about her being the invisible wife.

DW: I think it’s huge, too. And to give up her own work! She was an editor for Vogue, and when she earned her journalism degree, she was one of the first women to graduate from that university’s journalism school. She was accomplished and intelligent. She just fell madly in love with him. She believed they were two halves of one person, so she believed they were meant to be together.

ESQ: How awful that after she gave up her journalism career for him, he left her for a female journalist.

DW: No kidding. She indulged his interests in other women all those years. She knew that women were powerfully attracted to him, and she always thought, "It’s just a passing affair." By the time she realized she had underestimated Martha Gellhorn, it was too late.

ESQ: At various points in this book, we see Hemingway respond quite volcanically to criticism. At one point, a friend came to Wyoming and offered feedback on his manuscript, only for Hemingway to throw his notes out the window and let them sit in a snowdrift for three days. Was he always this hostile to criticism?

DW: Always. From day one. When he arrived in Paris, he arrived as a young man who wanted to be a writer, but he didn't have a single literary credit to his name. He had journalistic credits, but he wanted to write fiction. Gertrude Stein took him under her wing and introduced him to modernism. Some critic once wrote that Hemingway was influenced by Gertrude Stein, which infuriated him. No one could ever compare him or criticize him. He always said, “Critics have it in for me.” If they didn't like something, it was because they had it in for him. He held grudges, and got into physical fights with critics. He wanted everyone to think he wrote without any teachers, influences, or peers.

ESQ: Are there ways in which Hemingway's life and legend are still felt in present-day Wyoming? Can you go to a bar in Sheridan and see a sign saying, “Hemingway drank here,” or something like that?

DW: The information about Hemingway’s time in Wyoming was first introduced in 2011. A librarian in Sheridan gathered up all of this fabulous research, but it's still coming to light publicly. Last year, Chris Warren released a book about Hemingway’s time in Wyoming. We were writing these books at the same time, and we said to one another, "I thought I was the only one writing this book." We were following the same breadcrumbs, but his book is more about Hemingway in Cooke City, and the hunting and fishing he did there.

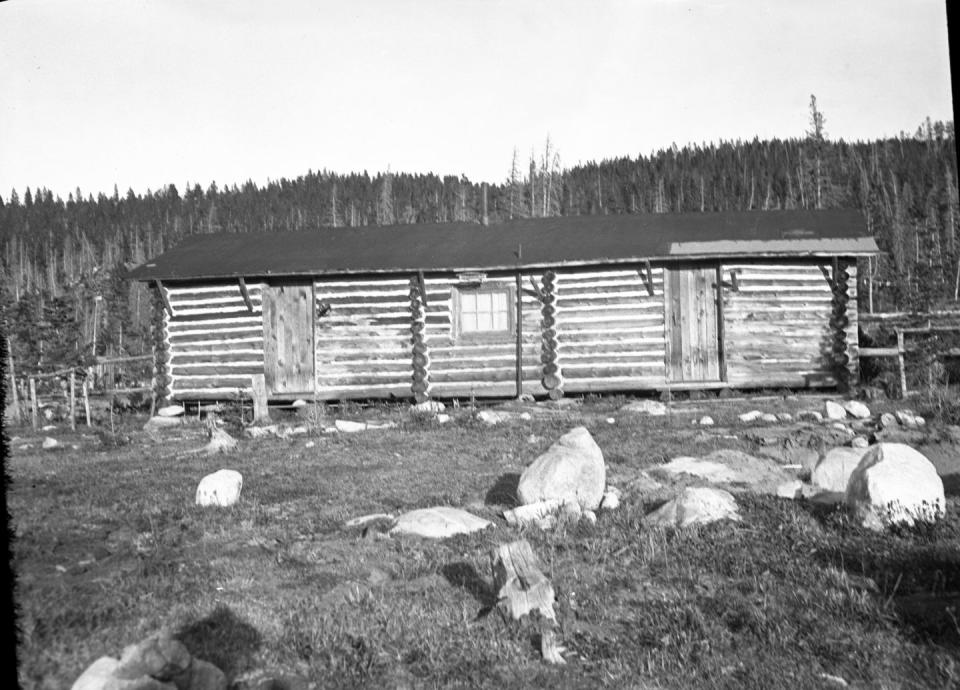

There's one place in the book, Spear-O-Wigwam, where Hemingway went up that first summer and stayed with Pauline. He finished A Farewell to Arms there; today, there’s a sign on the cabin labeling it The Hemingway Cabin. When I went looking for the Nordquist Ranch so I could photograph it, it was hard to find. A corporation owns it now, and has posted “keep out” signs all over. Most of his places have kept quiet. There’s a hotel in Cody with his signature on a guest register, but so far, that and the cabin are the only two things I’ve seen in the wild.

ESQ: You’d think the entire region would want to claim Hemingway and make a big fuss about his time there.

DW: Here's the funny thing: when I started the Left Bank Writer's Retreat in Paris, I had this idea that I was going to go to Paris, follow Hemingway’s footsteps there, and write a book about that. People in Wyoming would say, "Darla, you have to come up to this ranch. Ernest Hemingway stayed here." I never believed them, and as it turns out, all of these stories are true. Every one of them.

ESQ: Do you think the emergence of this information could lead to changes in the region?

DW: I do. I heard that the Spear-O-Wigwam dude ranch has been sold; they've already contacted me and are putting information about Hemingway’s time there on their website. The new owners are marketing savvy. Some of the other places, like the Chamberlain Inn, are surely going to use this in their marketing. I think they have a Hemingway room, or they at least have photos on the wall. People have never connected him with Wyoming, yet it was a really important place to him, where he had a lot of incredible adventures.

I did a reading and a book signing in Big Horn last week, where I met a woman who once rode in a car with Martha Gellhorn. She was a much older Martha Gellhorn and this woman was a child at the time, but still—she met her. Another man told me that he once saw Ernest Hemingway walking down Main Street in Sheridan; his father pointed Hemingway out to him. I think more of these stories and connections will come out as people gather and talk about him.

You Might Also Like