Do Climbers Have Expiration Dates? A Lifer Contemplates His Old Age

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Originally published March 2019

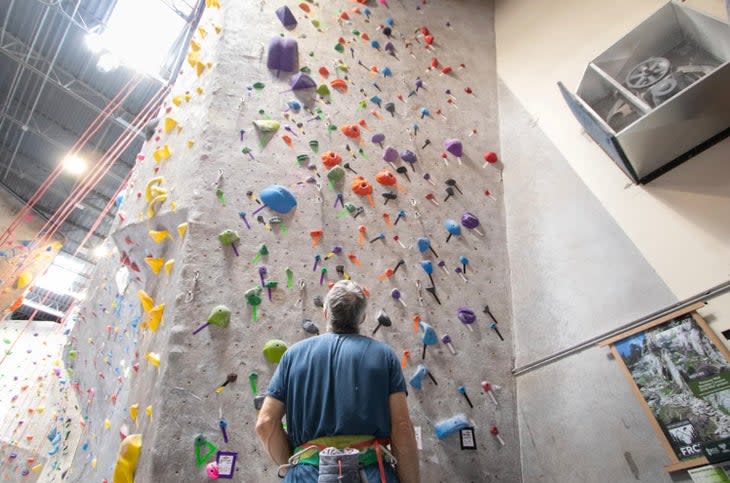

There is a wall at the Boulder Rock Club in my hometown of Boulder, Colorado, that fills me with a particular dread--that because of a few cognitive leaps in my obsessive mind has become inextricably linked with the notion of mortality. Flat, gently overhanging, and tucked into an angled corner, the Mary Beth is no more or less dangerous than any other wall in the gym, being, of course, a gym wall with pre-installed quickdraws every five feet, a padded floor at its base, and holds bolted tightly to the surface. But for some reason, 10 years ago, I built a whole dark narrative around it.

Monolithic features like the Mary Beth provoke a certain reaction in climbers--a quick intake of breath, a coiling of the bowels--and I'd hazard that this is where it all began on some subconscious level. I was climbing on the wall a decade ago with my wife when I suddenly, apropos of nothing, pictured it stripped bare of its holds. Just a flat, dark panel with little bolt holes encircled by white penumbrae of chalk.

What if we came in here one day and all the holds were gone and there was no way to the top of the wall? I pondered. But then we had to climb it anyway?

This impossible, irrational paradox congealed like a blood clot. Nobody could climb this wall without holds. Hell, Adam Ondra could belt-sand his fingers to the bone to fit the bolt holes, but there'd still be nowhere to put his feet. Plus his phalanges would probably snap off halfway up.

From there, my next thought was: This wall will still be standing long after we're dead, the holds always changing but the surface underneath remaining exactly the same. Flat, blank, immovable, inert. There was a metaphor in there somewhere, something about impermanence, but I let it go, as one tends to do in the face of such thoughts, and continued climbing.

A week or two later, I was shoeing up to climb a route on the left arete of the Mary Beth where it meets a brighter, more open pillar facing the entrance doors. A friend, Fred, came over and we started chatting. He'd read a column I'd written about feeling, in my late thirties, like my best years of climbing were behind me and that, as the injuries accumulated and my body slowed down, I'd aged out of performance climbing. Fred is a few years older than me, and he'd said, "You're only 37? Man, wait till you hit 40." Now, a decade later, with my hair whiter, knees creakier, and fingers more swollen, I can only look back and laugh at my relative youth and naivete. Ten years have gone by and I can feel each and every one of them, but the Mary Beth seems to be no worse for wear. It's clear she'll be standing long after I'm gone, a fact that somehow feels cosmically unfair.

* * *

The mental calisthenics I've indulged in over this one little slice of gym wall have propelled me to continue thinking about gym climbing in a metaphysical way, and I've come to realize that the life cycle of a gym climb very much mirrors our own. Such are the thoughts you have when you wake up at 5:15 a.m. two days a week to train before work, and are left alone, staring out at the holds from some dark recess in the bouldering cave at 6:00 a.m. before the sun has even risen.

Consider: When those freshly washed holds and bright, new swaths of tape go up, the climb, like a baby or young child, is everyone's darling--sought-after, mysterious, endlessly charming, close to the source (in this case, the setter). Soon the holds begin to discolor with chalk and boot rubber to match the older, more well-used grips around them, the route's beta becoming a known entity shared amongst the gym regulars, perhaps with tick marks appearing on key spots on the larger grips and volumes. The climb could then be said to be in its adolescence or early adulthood, finding its natural place in the world. As the weeks pass, the holds become slicker and the tape starts to curl, fray, and peel; the route is in its middle age--still viable, sure, and maybe worth a warm-up or cool-down lap, but nowhere near as sexy as that new "yellow tape" over there, what with its frictiony volumes, crispy foot jibs, and still-unlocked sequences. Finally, the route nears the end of its cycle: the final week. It's gotten a number grade harder from polish and chalk smegma, nobody has brushed the holds in days (or ever), the route is missing half its tape, and your feet keep sliding off the crux jibs. Like a senile grandparent shipped off to some purgatorial memory-care center in the exurbs, the route languishes in a corner, lonely, abandoned, awaiting its inevitable end.

Of course, most gym climbs have an expiration date written on them; we humans are never so lucky.

* * *

There is, however, a silver lining to all this existential/rock-gym angst. While we can never exactly know our own expiration date, knowing that a gym route or boulder problem has one can spur us to athletic greatness. That is, knowing we can't try our "plastic project" indefinitely, as we would a rock climb, we may get off our ass and do whatever it takes--training, cleaning up our diet, visualization, maximum try-hard--to get up the damn thing before it turns into an irredeemable grease-fest or the setters consign it to nonexistence.

As I write this, it's mid-March in Boulder on an El Nino year, and I've grabbed the rock maybe three times in the past two months. Since October, storm after storm has lashed the Rockies, bringing bitter winds, gray days, Siberian temperatures, and snowstorms both formidable and anemic to the Front Range. This coming Sunday might finally be properly warm enough to climb--54 and sunny--but finding dry rock will be another matter. Topouts are plastered in ice, black streaks course with melt-water when the sun peeks out, the canyons are gloom, snowdrifts, and shadows, and the Flatirons look like frosted wedges of upended wedding cake.

But the gym's been in season--the gym's always in season! And so, it's been a natural pivot to cultivate projects there, routes and boulder problems that take more than a try or two and might even take days. (I realize that for comp climbers, gym rats, and other assorted weirdos, having a project inside is nothing new, but I'm an old-school rock climber who--as good as gyms have become since the era of slippery plywood, monodoigt panels, and glued-on rocks--is only slowly evolving out of seeing them as mere "training," so please forgive my, er, crust.) And so, in the past few weeks, I've worked on and sent "white tape" and "white tape," but I'm still kinda working on "white tape" because my core went offline today on the final move to the lip, and I slipped from two crimpers and face-planted on the floor (oof!).

For the first two "white tapes," there was no urgency--I did them within the first week or two of their six-week life cycle, and could tell they were within the realm of the possible during initial, exploratory burns. But white tape, well, FML. I'm on day four or something and am only now consistently doing the sequences. It's a nuanced boulder problem at The Spot gym, requiring a carefully sequenced ballet of hand and foot switches. For the first couple days I could barely hang the grips, then I could only do a move or two at a time, then finally this morning I almost did the problem. As I packed up to leave the gym, I looked around for the setters, who usually come in on Tuesdays to strip and re-equip a new sector. I didn't see them or their baskets of holds, so I figured I was safe for at least another week.

All of which means, I need to stay focused, fit, and on track if white tape is going to go down. I can't slack off, eat Twizzlers for lunch, and "come back whenever," because at some point "whenever" will end. Which in a way is pretty cool: This ticking clock is an artificial, external pressure, sure, but an effective one nonetheless. What if you knew your project at Rifle--the one you hung your draws on, on the first day of the season, after training specifically for it all winter--was going to simply fall down after six to eight weeks, or whatever the setting cycle at your local gym is? (Come to think of it, at Rifle, where the Arsenal experienced a catastrophic collapse that erased or re-routed a handful of popular climbs in the 1990s, this is a distinct possibility.) I bet you'd give it 100 percent on each and every burn in April and May, no whining, no excuses--just kneebarring to glory.

The good news, at least in the gym, is that there are a few workarounds. App-driven tools like the MoonBoard, Kilter Board, and Tension Board mean that problems logged in the database will be around indefinitely, for you to try as many times as you want. And you can even, as one Boulder climber did some years ago, pay the gym to keep a route up until you redpoint it. (The climber, a successful author, wanted to redpoint a 5.12+ on the Boulder Rock Club's overhanging Tsunami Wall, and so paid the gym to keep one route --white tape, as it so happens--up until he'd succeeded.) But these solutions only stave off--or appear to stave off--impermanence. They can't stop the clock in real life.

In real life, there is that pesky expiration date, and our tape gets a little more faded, curled, and beat up with each passing day. The surface--be it the Mary Beth or the world beneath our feet--remains essentially the same. But at some point, the holds need to change.

Also Read:

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.