Climate change won't cause death to humanity – but air travel might

The likeliest thing to wipe out humans isn't climate change, it's the next pandemic. With the anti-vax movement, our growing resistance to antibiotics, and the speed at which air travel can spread disease – a modern version of the Black Death would decimate us

We do love a bit of doomsday drama. Humans have been predicting the end of the world for as far back as we have records.

Historically this fear of an impending apocalypse has been bolstered and exploited by religion (a great way to keep the masses in check), and more recently by the environmental movement, itself a quasi-creed, led by the likes of Al Gore, Dr Michael 'Climategate' Mann, and Extinction Rebellion.

"Civilization will end within 15 or 30 years unless immediate action is taken against problems facing mankind," said Harvard biologist George Wald in the 1970s.

"This [Climate Change] is the biggest crisis humanity has ever faced," said Greta Thunburg in 2019. Boris Johnson was singing from the same hymn sheet today at the launch of the United Nations Climate Conference.

While Wald, and many before him, were quite patently wrong, and though it's too soon to say whether Thunburg's thundering rhetoric will prove prophetic: what is certain is that climate change has already wiped out countless species over billions of years – none of it, so far, caused by humans.

We're overdue the next Ice Age; that really will throw a pick axe into the works and prompt a mass extinction. But perhaps the more interesting question is whether humanity will destroy itself before then? And if so, how?

Telegraph Travel spoke to Dr Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiology research scientist and author of several popular science books.

"I don't believe man-made climate change will ever lead to our extinction, or collapse human civilization," he says. "It will be very, very bad, but not existentially catastrophic.

"Something like the outbreak of a particularly virulent virus or very infectious, lethal pandemic is a low probability event, but exactly the sort of thing that catastrophe analysis and disaster planners take very seriously."

Low probability, perhaps. But it's happened before, and at eerily regular intervals...

Humans: a potted history of pandemics

Civilisation – which Wald predicted would disappear by the end of the 21st century – has been around for 6,000 years or so.

"Historical records suggest that about once every 1,000 years, an event occurs which wipes out about a third of the human population," stated Dr Simon Beard, at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge, to the BBC.

In the Middle Ages, this was the Black Death, when bubonic plague spread across Eurasia and claimed one in every three inhabitants. There was also a 'dramatic global cooling' at that time, incidentally; cause unknown.

"Around 1,000 years before that, there was a similar event with the Plague of Justinian [an epidemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire] and again, a lot of people died," Beard says.

Go back further, some 76,000 years ago, and there was "quite likely a certain event on a much larger scale", Beard continues, a mysterious event which wiped out 90 per cent of the human population. Genetic evidence suggests our numbers may have dwindled to about 10,000.

You might be wondering, based on this model, when we're next due a major population loss? One thousand years from the Black Death would bring us to 2350, but only half way into that timescale, we were dealt a pandemic even worse than that; the Spanish flu of 1918, which infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide, accounting, once again, for a third of the world's population.

The next pandemic could be far worse

History dictates that it is almost inevitable, sooner or later, that another particularly virulent disease strain will attack humans faster than we can formulate a cure, only this time, there's a big difference: air travel. The recent coronavirus outbreak provides a good example of how quickly a domestic bug can go international.

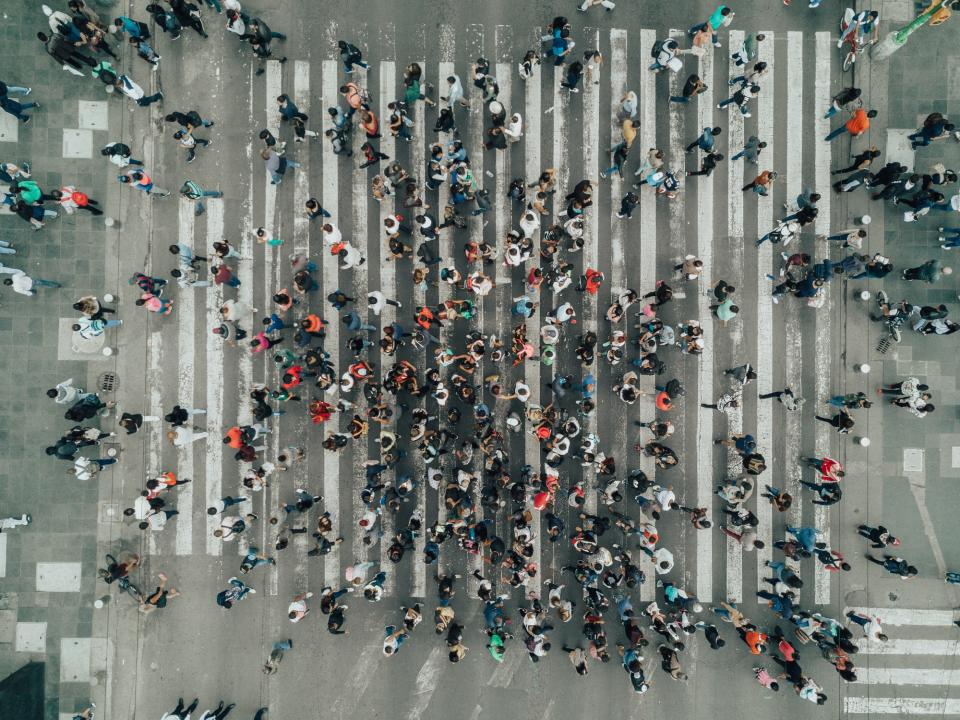

"The very way we live in the modern world, in densely packed cities, with planes that effectively teleport us between continents – more than 4 billion of us a year – these are the ideal breeding conditions for pathogens to spread wide and far extremely quickly," says Dartnell.

"Medicine may have advanced hugely in the past century or so, but where we live and how we move has made it easier than ever for diseases to spread. The quicker they can spread to lots of people, the less chance you've got to develop a cure in time or implement quarantine."

Quarantine, after all, was the best weapon people had in the Middle Ages when the Black Death hit. "Eventually they closed the ports, and incoming ships would be made to bob from afar for 40 days," says Dartnell. "That's where quarantine originated."

Just imagine the consequences today: several years of an incurable plague that air passengers spread globally within the first few days.

Other factors

As a species, we've never been healthier or lived longer. Advancements in medicine over the 20th century have been staggering, but amid these achievements is a poisoned chalice, Aside from the irony that keeping ever more people alive so successfully has led to an overpopulation crisis which at some point will break us, two of the drugs that have been so pivotal could at some stage be obsolete: vaccinations and antibiotics.

"Many of the medical breakthroughs of the last century could be lost through the spread of antimicrobial resistance [when pathogens mutate to outsmart antibiotics, rendering them useless]," warns the World Health Organisation. "Previously curable infectious diseases may become untreatable and spread throughout the world. This has already started to happen." The Infection Diseases Society goes further, describing antibiotic resistance as "one of the greatest threats to human health worldwide."

Dartnell agrees. "There is a genuine risk of antibiotic resistance taking us back to the pre-1920s era of medicine," he says. The problem stems partly from the overuse or misuse of drugs like penicillin, partly because we consume the meat and dairy of animals pumped with the stuff; and the solution - to keep developing new, better antibiotics - is too expensive and risk-addled for most major drug companies to invest in.

Then there's the anti-vax movement, which has seen a growing number of people around the world refuse to vaccinate their children based on misinformation about them being harmful. "It's a catch 22," Dartnell remarks. "Our science and technology has got so good at preventing the infectious diseases that would have killed nine children out of ten before their second birthday a few generations ago, that people no longer fear them, to the extent that they are choosing to not vaccinate their own children. People have forgotten what the problem was in the first place."

Grim. How can we ensure we don't go extinct? Ask a crocodile. In their current form, they have survived 280 times longer than we have.

This is the first in a two-part series. Next, we examine overpopulation; the root of every problem mankind is currently facing, and hear from Dr Dartnell on what would happen immediately after an apocalypse, where in the world would be best to camp out, and how we would rebuild society.

Dr Lewis Dartnell's book, The Knowledge: How to rebuild our world after an apocalypse, is out now.