Civil Rights Pioneer Claudette Colvin on What It Takes To Be an Activist

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Interview by Rachel Williams/

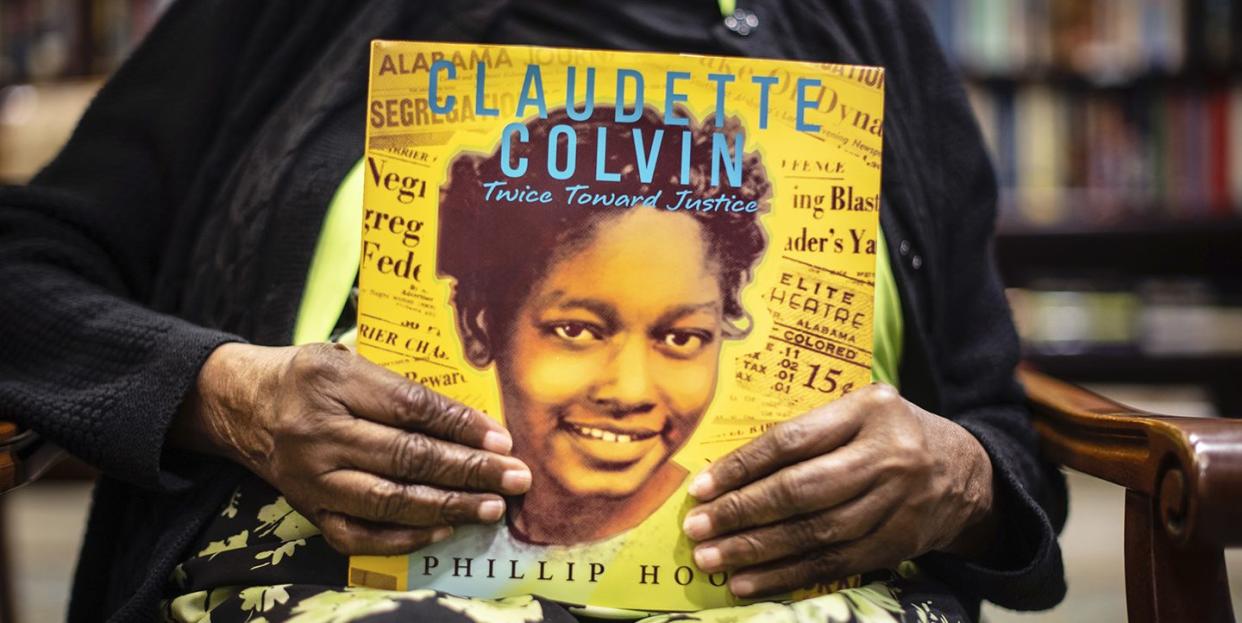

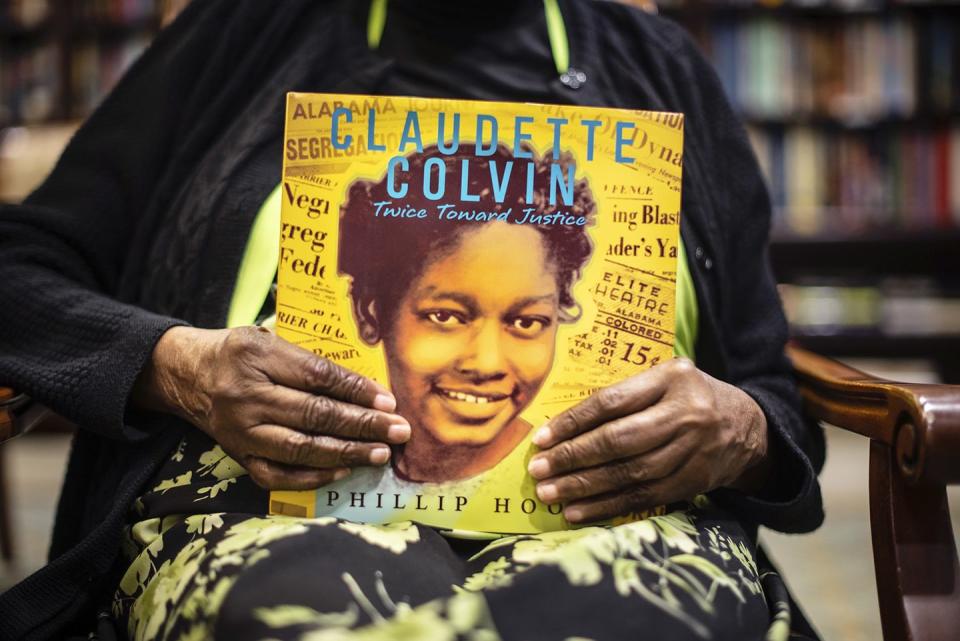

Photograph by Andi Rice

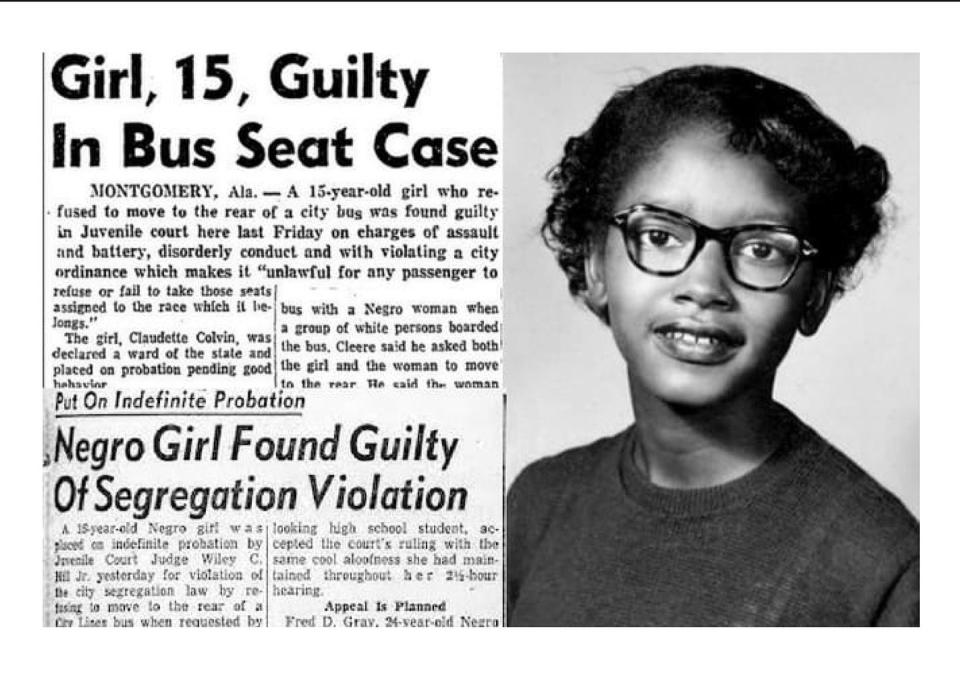

Claudette Colvin, 81, was a true pioneer in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1955, when she was 15, she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white woman—nine months before Rosa Parks’s refusal in Montgomery sparked a bus boycott. As an adult, she worked as a nurse’s assistant in New York City until her retirement in 2004.

ON GROWING UP IN THE SOUTH

“I lived with relatives on a farm in the little town of Pine Level. We had horses, cows, pigs, chickens, a dog, and a cat. All the big holidays were like a family reunion—my relatives would show up in big, shiny automobiles from the North. At that time we didn’t have electricity, so the little boys would take turns turning the crank on the ice cream maker. We made stew from scratch and had a barbecue pit. It was so much fun!”

ON HER FIRST ENCOUNTER WITH RACISM

“When I was 6 years old, I was looking around with my mother in a store to get a lollipop. Suddenly all the kids were laughing, so I turned around and said, ‘What’s so funny?’ A little white boy said, ‘Let me see your hand.’ So I raised my hand, and he put his hand up against my hand. Out of nowhere, my mother, Mary, popped me on the forehead. And the boy’s mother yelled, ‘That’s right, Mary!’ When I got home, my mother explained that I was never to touch or talk to a white child.”

ON NOT GIVING UP HER SEAT ON THE BUS

“I was a teenager at the time, and we had been learning about Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth in school. When a white woman got on the bus and the driver told me to get up from my seat so she could sit down, I felt that those women each had a hand on my shoulders pushing me down. History had me glued to the seat. The police dragged me off the bus, handcuffed me and took me to jail. Later that day, my mother and a local pastor bailed me out, and that night after I got back home, my father sat up with a loaded shotgun by his chair. He said, ‘The KKK is not going to take you out tonight.’”

ON ROSA PARKS

“After I got out of jail, I lost most of my friends because their parents told them I was a troublemaker. Then I got pregnant out of wedlock and had my son Raymond. At that time, Rosa Parks was the secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, and as a seamstress, she had a lot of white, affluent customers. So, she became the face of the movement, and I was ostracized by a lot of activist organizations. But I wasn’t seeking notoriety. In fact, Ms. Parks became a close friend and mentor to me after I joined the NAACP Youth Council. We have to remember that Black women may not always have all the support they need growing up. Struggles you’ve gone through have nothing to do with your capabilities as a leader. It’s a shame to miss out on so many precious minds and contributions.”

ON THE LESSONS SHE WANTS TO PASS ON

“Don’t be afraid to stand up and fight for what’s right. Get out there in the struggle. The more of us are out there, the more powerful we will be. You might not benefit from it right away, but the younger generation behind you will benefit from it.”

ON WHAT SHE’S MOST GRATEFUL FOR

“I’m most grateful for raising my two boys to adulthood. I provided for them and gave them courage. I can say I have reaped some of the fruit of my labor through my grandchildren. These are the last days of my life, but God has blessed me. I don’t have money, but I have hope and faith.”

About the Journalist and the Photographer

Turn Inspiration To Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

Credits: Andi Rice: Amanda Rice

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like