‘Cinema for the ears’: the unlikely rise of audio books

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

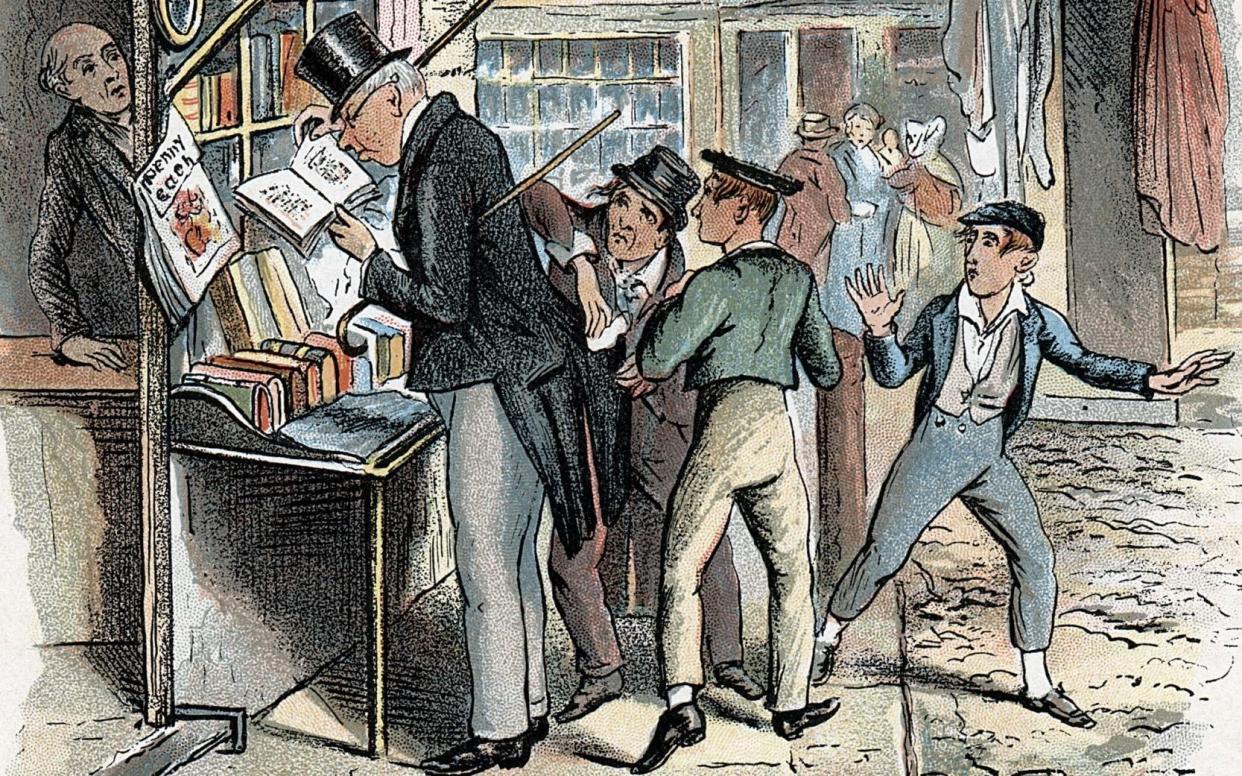

At the beginning of this month, Audible announced a major partnership with the Oscar-winning director Sam Mendes. Mendes will direct three adaptations of Dickens, beginning with Oliver Twist, featuring an as yet unannounced cast and recorded at Audible studios and on location using foley techniques in Rotherhithe. Audible, established as an audio book company in 1995 and bought by Amazon in 2008, are well used to working with celebrity talent – their Idris and Sabrina Elba podcast was one of the hits of lockdown – but the Mendes commission, with its anticipated blockbuster production values and A-list creative sheen, feels like a game-changer. “Technology has come a long way in audio,” says Aurelie de Troyer, senior vice president of international English content at Audible, whose aim with the big-budget adaptations is to create a “cinema for the ears”.

This seems a very long way from the days when audio books meant chunky Catherine Cookson cassettes. Far from being consigned to the analogue dustbin of history, the audio book has been reconfigured for the digital age. Now, you can listen to Benjamin Zephaniah and Cerys Matthews read Robert Macfarlane’s poetry collection The Lost Words, replete with field recordings to emulate Jackie Morris’s original nature drawings, or Charlie Mackesy’s hit book The Boy The Mole The Fox and The Horse featuring a lilting soundscape by Max Richter.

The rise of binaural tech (which conveys the uncanny effect of 360-degree sound) means listeners can experience the audio adaptations that use it as though they are standing in the same room. One of Audible’s recent biggest sellers was an aural reconstruction of Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel The Sandman, featuring James McAvoy, Riz Ahmed and Taron Egerton with a doomy, epic immersive soundtrack. Listening to it feels like having an Imax cinema in your brain.

Audio sales, of course, have been growing steadily for years, helped by the rise of the celebrity narrators such as Elisabeth Moss and Stephen Fry, whose plummy avuncular tones are often more of a draw for listeners than the book he is narrating. Nor has their rise always been a good thing, as parents forced to endure David Walliams reading one of his interminable books during a long car journey will testify. In fact, children’s audio on Audible is a case of quantity over quality, with most consisting of bewilderingly popular mass-market authors reading their own rather bad books, instead of stimulating adaptations.

All the same, while the market share remains relatively small – audio accounted for 6 per cent of sales across all book formats in Britain in 2020 – it increased by 71 per cent in the first six months of 2021 compared with the same period in 2019. The boom coincides with the coming of age of podcast culture, but also with the pandemic, which not only imposed unexpected leisure time on millions across the world but also pushed more and more of us to live inside our heads. Three and a half billion hours were spent listening to Audible worldwide between 2020 and 2021, an increase of 25 per cent.

Meanwhile, cheap storage on smart phones means downloading audio files is much easier than it was even a few years ago. We can walk around with hundreds of books inside our pockets.

Yet what does this growing influence of audio culture mean for our relationship with books – and with other art forms, come to that? Does Audible’s growing market share, eye-watering marketing budget and increasing cultural prevalence mean that we’ll soon turn to glossy Audible adaptations of classics, rather than sit down with the humble book or Sunday-night TV adaptation? One wonders if millennial Dickens buffs will opt for the BBC’s forthcoming Christmas TV adaptation of Great Expectations over a Mendes production on their phones.

And where does Audible’s rise leave British publishing audio departments? Many have a vast reserve of texts at their fingertips, yet there is a sense that they are being left behind. They tend to produce straight audio books with single narrators which don’t have the same dramatic appeal as a multicast, whizz-bang adaptation for today’s audio-literate generation.

“I don’t see Audible as a threat,” says Richard Lennon, audio publisher at Penguin Random House, which also licenses BBC audio adaptations. “We’re very much a book publisher, we know that huge numbers of people come to books through listening and our job is to make our books as accessible as possible.” He points to the Terry Pratchett Discworld series, recorded with multiple casts, and the 2000 AD comic book adaptations – both Penguin productions – as audio books that remain faithful to the original while offering an enhanced sonic experience. “Where we need to do something very creative in order to reproduce the book, we will do that but I don’t see the need to become a different type of audio producer at the same time,” he says.

Yet there’s no getting away from the fact that audio’s mushrooming popularity and growing technological capabilities are shaping how we experience books, and even how we write them. At Edinburgh International Book Festival, the producer Emma Balch is presenting her dream-like audio production of Sandro Veronesi’s The Hummingbird, first heard on Radio 3, in the form of an immersive hour-long installation on August 29. Lennon mentions Malcolm Gladwell’s non-fiction 2019 book Talking to Strangers, conceived with the audio version in mind: the latter contains excerpts of the interviews in the book with an original score.

The rise of audio books has also attracted those in other creative fields. Composers Ben and Max Ringham, who carved their careers in live theatre production, have produced their first audio drama, Exemplar, featuring Gina McKee as a leading forensic audio examiner, which launches on Radio 4 on Aug 19. Natalie Abrahami recently developed the original ghost play Descent for Audible, using binaural technology to enhance the story’s creepy atmospherics.

Meanwhile, podcasting has long been a powerful creative driver of its own, inspiring shows like Hulu’s miniseries The Drop Out, based on an ABC News podcast. Apple is rumoured to have paired up with podcast producer Futuro Studios, with a view to turning resulting podcasts into films or TV series.

Yet Lennon is wary of overstating what’s going on. “Yes, audio books and drama are going through a huge resurgence, but it’s not a threat to other forms of media,” he says. “It’s about how a particular individual wants to experience that story. After all, oral storytelling is literally the oldest art form in the world.”

Indeed. Not so long ago, it was the screen that became the modern portal to a new universe of stories. Now it’s the lowly set of headphones.