Christine Barker’s Memoir, ‘Third Girl From the Left,’ Places Her at the Intersection of Broadway and the AIDS Epidemic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In her new memoir, “Third Girl From the Left,” Christine Barker writes about interrupting her burgeoning showbiz career as a dancer in “A Chorus Line” to care for her older brother, Laughlin Barker, former president of Perry Ellis International, who was dying of AIDS.

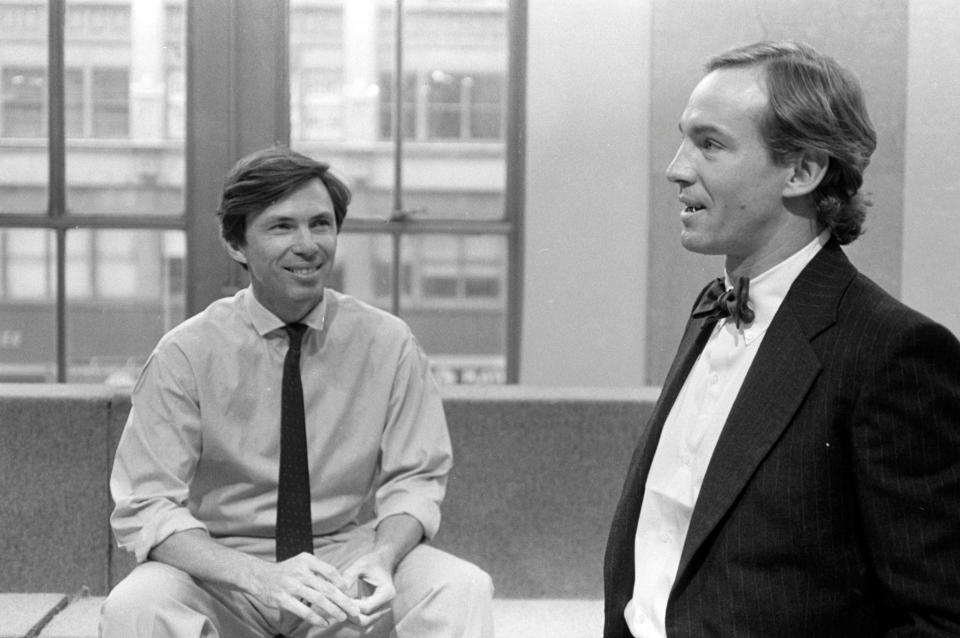

This was in the mid-1980s when there was so much ignorance and stigma associated with AIDS that neither Laughlin nor his business partner and lover Perry Ellis would disclose their illnesses. At the time, their failing health was shrouded in secrecy to protect their highly successful business, the employees and the brand, which had established itself at the forefront of American fashion for easy, understated dressing. In fact, in 1986, their obituaries attributed their deaths to lung disease for the 37-year-old Laughlin and, four months later, viral encephalitis for the 46-year-old Ellis.

More from WWD

Christine Barker starts her book talking about leaving her hometown of Sante Fe, New Mexico, to pursue a professional dance career in New York. She studies with Alvin Ailey, Luigi’s Jazz Dance Centre at the American Ballet Theater School and gets jobs in summer stock, dinner theater and national tours. After dancing alongside Tommy Tune, she meets musical theater director Michael Bennett and wins the role of Kristine in the London production of “A Chorus Line,” the groundbreaking musical about Broadway dancers baring their souls as they audition for a musical. She then joined the New York cast, with which she performs for six years.

“I was in heaven. I was living my dream. How lucky to be in your 20s and you are living your dream. So many people don’t get that chance in life. Believe me, I was so aware of that as a dancer. So many people could never get what I got, and I thanked Michael Bennett and God every day,” says Barker during an interview in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Just as her career was taking off, her brother Laughlin, who helped build Ellis’ business with key licensing deals such as the Perry Ellis America deal between Perry Ellis and Levi, Strauss & Co., was diagnosed with AIDS, and she left the Broadway show to care for him.

What’s interesting is how much Barker is able to recall from that era, which she attributed to her grandmother, who spent the last week of her life with Barker and told the then-12-year-old girl that she should always keep a journal.

“My father was in the military, we moved everywhere, we lived in Europe as a child, and she said, ‘You have very interesting life experiences. You should always keep a journal.’ It made an enormous impact on me,” Barker says.

She says she started keeping journals and had boxes of them. When Laughlin told her he had AIDS, she was sworn to secrecy because he was so concerned about what would happen with the business. He felt the business would die “and thousands of people would lose jobs.”

She says the pressure was enormous. “And the way that I coped was the writing. I would be with him and Perry at their house, and I would take the subway back downtown, and I would write on the subway. I have legal pads and some parts of my book were lifted exactly from that,” she says.

Barker says she knew instinctively that she had a story. “I come from a theater background and you understand story when you do theater, and you particularly understand story when you’re doing ‘A Chorus Line,’ because ‘A Chorus Line’ is beautifully written. It appears to be very simple, but it’s very highly constructed in the stories that they tell and what they chose to tell. And how it teaches you to tell a story where there’s a sense of purpose and a sense of urgency,” she says.

“A Chorus Line” featured real stories from real people. Originally, Bennett had invited dancers to come to workshops and talk about their lives. The people whose stories were used got a percentage of the show, and the people who played the original parts also had a small piece. Some people didn’t get hired to play themselves, but their stories were used or were blended.

In the book, Barker gives a behind-the-scenes account of the highs and lows of dancing in “A Chorus Line,” when the spread of a devastating disease is all around her, destroying a generation of artists. She describes the horror of going through such a situation with so little information, the need to keep everything a secret and the devastating impact of stigma.

Barker says that when she saw Larry Kramer’s “The Normal Heart” at the Public Theater in New York, she felt people could only get the truth when they went to the theater. “He wrote the truth, and every day at the Public Theater they reported statistics. The Gay Men’s Health Crisis hadn’t been formed yet, ACT UP hadn’t been formed yet, there was nothing. What there was was this play and Larry Kramer, and people could get statistics there. You could not get statistics in The New York Times. By writing that play and Joe Papp producing, it was enormously powerful. When I saw that play, and knew what was going to go on [the decline of someone’s health once they had AIDS], that’s when I decided to leave and take care of Laughlin,” Barker says.

She never had any regrets about quitting the show to become Laughlin’s caregiver, “although it changed it changed my life drastically,” she admits.

“You see this over and over again. Women who are faced with very difficult choices and become caregivers. I never regretted it because I spent the last part of his life with him. I spent the last part of Perry’s life with him. I spent the last part of a lot of my friends’ lives with them. What I learned about life and what I learned about making choices and making decisions — one thing I became very aware of is how women are impacted in times of emergencies,” she says.

Barker says her brother did not come out of the closet for a very long time; he married a woman in 1971, served in the U.S. Navy; had a daughter, Kate, and had gotten divorced.

“When he went to Georgetown Law School, it was basically against the law to be gay. He had a job at a white shoe law firm, and he would have been fired. It was only when Laughlin met Perry [around 1979-1980] that he had the confidence to say he was gay. I knew he was gay, but nobody in my family did. He and Perry lived privately. They were not ostentatious. They were the star couple because they showed that gay men could have a life together, and they didn’t have to be afraid and they could go out in public. That’s what they did. They weren’t going to advertise it, but they also weren’t going to deny it.”

In the book, Barker describes how Laughlin and Perry’s relationship just clicked, although their personalities differed.

“To the relationship, Laughlin brought a more tempered, Madison Avenue sensibility with his Georgetown law degree and extensive experience living and working in Europe. Perry was a master of promotion, well-mannered like a Southern aristocrat, but with a shyness that masked coldness and rigidity. Laughlin was the opposite. He was charismatic and warm. He could endear himself to the cleaning staff as easily as Georgia O’Keefe, which he once did at a museum opening, when after being introduced she ignored the press and walked around the exhibit with Laughlin,” Barker writes.

In the mid-1980s, the press was skittish about reporting on gay life, she says. “The lack of information, no social media, led to misinformation, confusion and fear, further isolating those of us dealing with AIDS,” Barker adds.

“There was such a stigma. People do not remember what that stigma was like and the stigma was merciless. The Reagan administration, the Moral Majority, Pat Buchanan and Jerry Falwell. Jerry Falwell was on TV saying, ‘AIDS is the wrath of God upon homosexuals,'” she says.

Following their deaths “there was so much talk about Perry, and there was never any talk about Perry and Laughlin’s relationship,” Barker says. “Perry’s obituary in the Times and most places never mentioned Laughlin. It was the business trying to separate themselves from Laughlin. That was very upsetting to me. [She says she didn’t get invited to Ellis’ memorial service at the Society for Ethical Culture]. Laughlin had created the Levi Strauss deal. He built the business from five licensees to 23.” She says the business became very successful when Laughlin took over Perry Ellis International.

(In Ellis’ obituary in WWD, Laughlin was described in the article as the designer’s “closest friend and companion.” In Laughlin’s obituary in WWD, there is no mention of Ellis as a survivor or companion.)

After Barker left the theater and many of her friends had died of AIDS, she raised her children and earned her M.F.A. in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, where she also finished her bachelor’s degree. She was in her 40s at the time.

Barker will be part of a book discussion at the Bryant Park Reading Room on Wednesday from noon to 1:30 p.m. She says she waited to publish her book until her parents — who lacked tolerance for their son’s lifestyle — died.

“My parents were of a different generation. That generation had it wrong, but I’m not interested in repeating that. I’m interested in telling the truth,” she says.

Best of WWD