Can Chris Whittle Launch a Truly Global University?

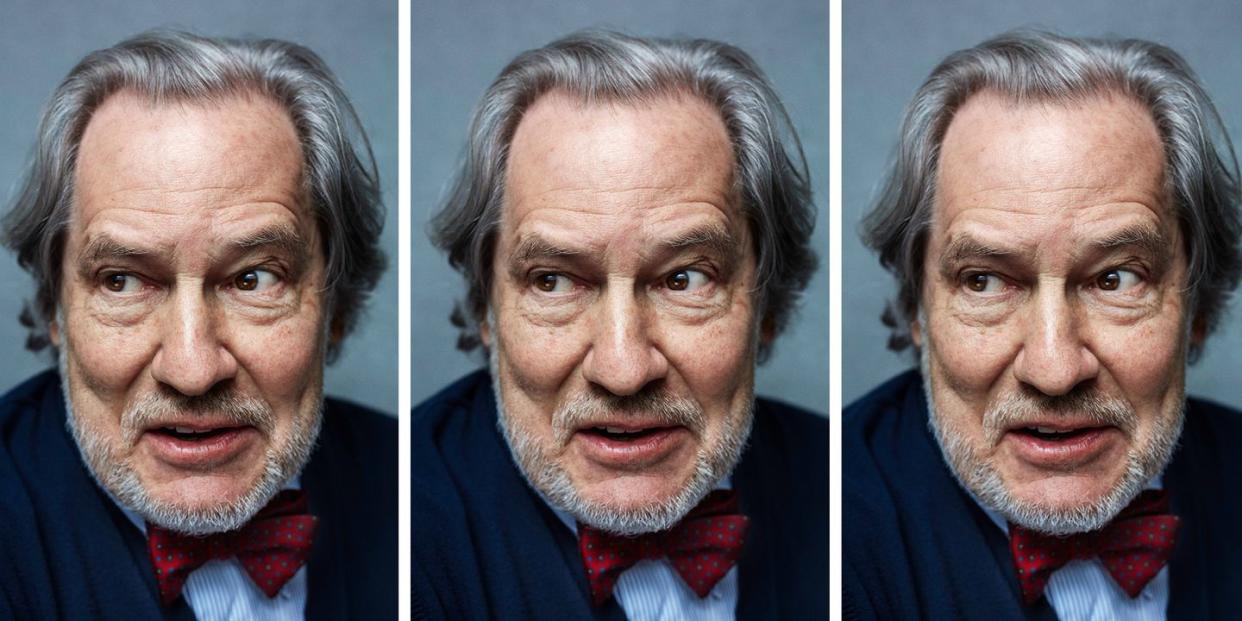

Portrait by Alexei Hay

Chris Whittle is seated at a table in the Garden restaurant, with its bright green copse of African acacias, in the lobby of the Four Seasons hotel on 57th Street in New York City. An iPad rests beside him next to a cup that has been drained of coffee. Whittle is 70 but looks younger. He has a Civil War general’s mane and a close-cropped beard on his wide, granite jaw. He is wearing a striped shirt under a V-neck pullover vest, but not the bow tie that helped make him one of Manhattan’s more vivid presences in the 1980s and ’90s.

It’s 10:30, and he could use a big breakfast, but he has to be in Boston in a few hours. He holds out his wrist. “My kids got me an Apple Watch, and I haven’t quite figured it out.”

Time is plainly on his mind. He has given himself a decade to complete his latest project-or scheme, depending on whom you talk to. Called Whittle School & Studios, it’s “the first global school, created by an international consortium of educators, artists, technologists, and experts in law, real estate, recruitment, and more,” according to the catalog.

“Did you get a copy?” he asks. I did, in the form of a PDF. Not good enough. Whittle pulls out a deluxe coffee table–style soft-cover that looks ready for end placement in the MoMA gift shop. Though an early techno wizard, he is also something of an antiquarian who in plusher times had paintings by Sargent and Doré on the walls of his two splendid apartments in the Dakota and later in the East Side townhouse he bought for $12 million.

Much care has gone into the production and design of his catalog, which is for now the most tangible evidence of the new vision, or empire, he means to create in the next 10 years: “one school with many campuses-in the world’s top cities-connected by a single faculty and a common curriculum operating with a collective intelligence."

Whittle is a world class bottler of the zeitgeist. Avenues, the for-profit independent school he helped create in 2012 and then abruptly resigned from in 2015 after losing a battle for control, is already famous, or notorious, in Manhattan, and not just because Katie Holmes can be seen at parent meetings. There are also the many Whittle flourishes: the remodeled Cass Gilbert landmark building, with its 25-foot “double-height” spaces and 10-foot-high windows, the high-tech gadgetry (a laptop and an iPad in every over stuffed backpack), and a dual-language curriculum that includes total Chinese immersion.

One of Whittle’s pet phrases is “old school”-not a metaphor but a literal descriptor of the competition. He is all about the future. And his newest idea-actually, it was the original Avenues plan before Whittle met resistance-is to grab globalism by the throat and wrestle it to the ground. At a moment when many Americans (beginning with the one in the White House) seem terrified of the outside world, Whittle envisions a giant plugged-in educational Shangri-La, with at least one school in each of “the megacities of the world.”

The first in the U.S. will be on the coasts (New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, Washington), and there will be 11-yes, 11-in China. They will be knit together into a small global empire, with a total “faculty of 10,000 serving more than 90,000 full-time, on-campus students as well as hundreds of thousands of other students joining us part-time, either virtually or on campus.”

The words school and campus seem outmoded. The architect is Renzo Piano, and the mockups show light- filled auditoriums, open-air spaces, clerestory atriums, and futuristic pre-K playrooms for tomorrow’s thought leaders.

“I grew up in a family that cared about design,” says Whittle, who comes from Tennessee and still speaks with a gentle drawl.“It affected me my whole life.” And Piano-a friend? “Never met him. My wife’s Italian and did know him. Her family knew him.” Whittle’s wife is the photographer Priscilla Rattazzi, who posed for Avedon and is a niece of Gianni Agnelli, the late owner of Fiat. Names are important in Whittle’s world. Not to drop-he has far too much taste-but to collect.

In addition to Piano, the glittery advisory board of Whittle’s new project includes former Yale president Benno Schmidt and Kwame Anthony Appiah, the distinguished NYU philosophy professor who also writes the popular “Ethicist” column for the New York Times Magazine.

Appiah is one of several advisers who will shape the Whittle School’s curriculum, a topic about which Whittle himself is curiously diffident. “Roughly comparable,” he says of the program of study, brushing aside petty distinctions between “your math and my math.”

In truth, Whittle has never had much to say about the things most people talk about when the subject is schools: teaching methods, subject areas, the mysterious working of children’s minds. “He promotes education reform but can’t name a single reformer,” a journalist noted in 1990, and this still seems more or less true. In a conversation that lasts an hour and three quarters, not one education thinker comes up. Prospective parents, staring at a $40,000-plus tuition and thumbing through the sumptuous catalog, with its 30 pages on “The Team and Extended Family”-dazzling résumés, studio-quality headshots-won’t find much of an answer to one obvious question: What will my kid be learning?

“It’s not technology-oriented, it’s human relationships–oriented,” Whittle says. In fact, his main innovation is “very old school: an advising system that is more like the Cambridge and Oxford tutoring system, where you have a coach in your school. Every faculty member is going to have nine kids.” All this, along with the brain trust skimmed from Ivy League universities and elite private schools, is meant not just to impress affluent parents who will pay top prices but also, crucially, to attract investors.

There, he excels. Since 2015 Whittle has raised $700 million in “operating and real estate–related capital,” and most of it is coming from top-tier financial institutions. He gladly ticks them off: “On the U.S. side, a private equity group: Clayton, Dubilier & Rice,” the 40-year-old Park Avenue firm. “The partners of Clayton-not the fund-all wrote personal checks” after a series of one-on-one meetings, Whittle says. And there’s more, much more.“The big groups are the wealthiest family in Taiwan, which runs a conglomerate called Fubon. A group that invests the capital of the largest bank in the world, ICBC, out of Hong Kong. A group out of Nanjing called Golden Eagle.”

The keystone to this vast structure is China. “In the past 20 months I’ve been there 37 times,” he says. “I spend almost half my time in China-half of the past seven years, every month. It’s just overwhelming to see what’s going on there, in so many sectors in so many ways. It’s inspiring.” The only drawback is, “For a guy my age the air can be a little hard to breathe, especially in the north. I had childhood asthma.”

In Beijing, Whittle got to know Yuan Bing, a partner at Hony Capital, a private equity firm, who has degrees in business and law from Yale. Yuan and his partners invested-out of their own accounts-much of the $28 million Whittle raised in his first round of financing. Yuan also helped Whittle select the site of the first of the Chinese schools: the city of Shenzhen. In China education is nearly a religion ,and everyone knows what good results look like. “These schools aren’t cheap,” Yuan says. “If kids don’t get into good colleges, it will be a problem.” Still, he’s confident. “This is a long-term investment. Eventually we’ll take the company public.”

For that to happen, Whittle’s program will have to unfold according to the schedule he has laid out: the first schools, in Shenzhen and Washington, DC, in 2019. Then Hangzhou and Nanjing in 2020; London, New York, Beijing, and Silicon Valley in 2021. Four megacities a year through 2026, by which time the points on the Whittle compass will include Paris, Delhi, Tokyo, and Doha. It’s preposterous, but also prodigious. And the seasoned Whittle watcher has to ask: Is this one more instance of his matchless salesmanship, his “remarkable ability to get smart people to do stupid things,” as one colleague put it long ago? Or might he have struck permanent gold-achieved at long last perfect harmony with the moment? Whittle’s answer is matter-of-fact: “It’s my last rodeo.”

There have been many wild rides through the years for Whittle, dating back to the 1970s, when he and two other University of Tennessee graduates started a downmarket magazine company in Knoxville that produced single-advertiser giveaway publications they sold as waiting room distractions to doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and health clubs. With titles like Pet Care Report, it wasn’t Condé Nast. In fact, it looked like rube fare, but there was genius behind it.

Whittle and his main partner, Phillip Mott, had tapped a sea change in the culture. The one-size-fits-all formula meant for family consumption-Time or Life or the Saturday Evening Post-was becoming antiquated. The electronic age-TV, radio-had splintered us all into smaller communities. Whittle realized that as a publisher his task was to locate a particular niche and carpet-bomb it, with ringing bells and ads from the sponsor. It was a forerunner of today’s microtargeting, the ad that suddenly appears in your e-mail, sneakily synced to your last three purchases, which you naively supposed were secret.

Whittle and Moffitt got there early-too early-and almost went broke. But they hung on, and in 1979, styling themselves “the fastest guns in the South,” Whittle (age 31) and Moffitt (32) swaggered into Manhattan and purchased the venerable but then fading Esquire, just when the city itself was down at the heels and begging for a makeover. With Moffitt as editor and Whittle as publisher, Esquire was reborn-a slick, knowing guidebook, plump with ads, for young climbers in the Bright Lights, Big City era.

Whittle was just beginning. By the end of the ’80s Whittle Communications had 900 employees and 19 magazines, plus newsletters, video-tape systems, and “information centers.” That’s when he made his next big gamble. Scanning the minds and habits of the next generation, he saw how MTV had colonized its bedrooms. Why not invade on another front: the classroom?

He started a television news company, Channel One, based on the MTV model, in 1989. It offered 10 minutes of news and two of commercial advertising, piped into classrooms on equipment Whittle would provide free of charge. There was instant alarm-from the National Education Association, the National Association of Secondary School Principals, PTA groups. Students would be captive minds force-fed “Pringles, Clearasil, and military recruitment ads,” as one critic remarked.

“There are only 15,000 school boards in the country,” Whittle says today. “We went to each one twice, on average: 30,000 meetings.” Eventually the network got into “40 percent of all the middle and high schools in the country.” Some people dispute his numbers, but most acknowledge that the content improved. The network even won a Peabody Award, thanks in part to its charismatic young anchor Anderson Cooper.

Whittle loves rattling off numbers but isn’t always precise about them. One reason is his continual need to scale up-to keep getting bigger at the fastest possible rate. In the '80s and '90s there were enablers all around. Even his adversaries in old media succumbed. Time Inc. invested a staggering $185 million in his company. That was fine, except Whittle, for whom living means living large, poured $50 million of that into his new headquarters in Knoxville (“Whittlesburg,” some called it), a palace “like an 18th-century Georgian college on the outside, with old-fashioned window sashes, cabinets, and incandescent lights,”one staffer from those years recalls, but also proudly high-tech.

All this was mere prelude to Whittle’s big idea, the one for which he is best known today: “independent schools.” That is, Edison Schools Inc., the giant network he envisioned in 1992 with the plan to create nothing less than a nationwide privately financed school system to compete with the state-run version-and for profit. He anticipated building 200 across the county within five years, and within 15 years 1,000 schools, which would educate as many as 2 million students. It would cost a fortune, $3 billion, but it would be an investment, with all manner of smart cost-cutting measures-reducing the number of teachers, for instance, and having the kids look after the school property instead of janitorial staff. “What is Chris Whittle teaching our children?” the New York Times nervously wondered.

One answer came in May 1992, when Yale president Benno Schmidt, hours before donning his robe to preside over commencement, told the university’s trustees he was quitting to join forces with Chris Whittle. It might seem “outlandish, like leaping into the abyss,” Schmidt allowed in a page one story in the Times. “But if this venture succeeds, there’s nothing that could be done, aside from changing human nature, that would be more constructive for our society.”

Two years later it came apart. “The McDonald’s of education,” as some called it, was not so well conceived after all, and it hit one snag after another. The nation’s new president, Bill Clinton, opposed vouchers, which scared off investors. Whittle got only one-tenth of the capital he had been counting on. The schools instead became charters, publicly funded alternatives to existing schools that got lackluster results in the inner cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia, where Whittle had been awarded contracts.

Meanwhile, his financial empire was crumbling. Time Inc. cut off funding. Others did too. “Whittle Communications LP has shrunk to a grab-bag of assets,” Bloomberg News reported in 1994. The private doubts about the company were now out in the open. The New Yorker’s James B. Stewart swooped in to do a long profile that dug into the crevices of Whittle’s finances, including as much as $10 million in unpaid business taxes. “Once the administrators of America’s public schools have absorbed the magnitude of Whittle’s failure with his other ventures,” Stewart concluded, “they are hardly likely to trust him with their dollars, let alone their children.”

Whittle lost his living-large trophies, too-the private jets, the costly paintings-though even the loss had a kind of lopsided splendor. For instance, when he and Rattazzi put their Gatsbyesque Hamptons palace on the market in 2014, Forbes reported that the asking price, $140 million, made it “the most expensive home for sale in the region, and likely on the East Coast.” Three years later, it hadn’t sold, and then last fall a disgruntled former business partner put a lien on it.

The big question often asked about Whittle is, What has he done forAmerica’s youth? He remains the first pioneer of what today is called school choice, which is very much still with us (just ask Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos). Back in 1991, Whittle projected 2 million alternatively educated kids. Well, today the number is 3 million, enrolled in some 7,000 charter schools across the land. With what result? Again it depends on whom you ask. They’re either a lifeline for middle- and lower-income children and their parents, or they’re part of the steady erosion-in funding and support-of a pillar of our civil society at just the moment when it needs shoring up. The debate is ongoing. Whittle suggests it’s too soon to say. “If you look at it over a 30- or 40-year frame, I think people are going to say it was historically significant and made a difference.”

He points to the triumphs of those who followed him, such as Eva Moskowitz, a former New York City council-member who founded Success Academy in Harlem in 2006 and now oversees 46 schools throughout the city that get eye-popping test scores, though critics question her martinet approach. When Moskowitz was starting out, she went to Whittle for guidance. “I felt my brain had been vacuum-cleaned,” he says. He exults in her accomplishments, and Moskowitz returns the praise. “Chris Whittle is one of the most imaginative, innovative education thinkers I know,” she says. “He is committed to the idea that there has to be a better way to educate kids.”

Whittle still believes in charter schools, but there’s no denying that his new venture is for the prosperous. “Eighty-five percent of the children going to our schools will be from very fortunate families,” he says. “Fifteen percent will be on scholarship.” Fortunate is a canny Whittle touch. It sounds like a euphemism, but in fact it hits a hidden nerve of anxiety in the white collar class: the worry that the wheel may swiftly turn against them, as it did for so many a decade ago, when the market crashed.

Whittle’s numerous detractors in the pedagogical world point to something else.“It’s all marketing,” says Samuel E. Abrams, an educator and the author of Education and the Commercial Mindset, a detailed critique of school privatization with many scorching pages on Whittle’s past projects. Abrams has closely studied the School & Studios catalog, and what strikes him most-apart from the A-list advisers and the faculty skimmed from Harrow and Exeter-is the staggering $700 million Whittle has raised, very little of it from the United States. The true narrative for this story is China. “The market is there,” Abrams suspects, because what Whittle is really selling, to prosperous and ambitious Chinese parents, is English fluency for their kids, whom they hope to send to top-tier American colleges.

Avenues was likewise conceived as a global project, and it still claims to be “the world school,” per its website, committed to “global readiness.” And it will one day be one of “20 or more campuses in major cities in Asia, Europe, Africa, and North and South America.” Whittle, naturally, wanted to build sooner rather than later. There was disagreement and then a power struggle. He lost. “Chris has amazing strengths in vision casting, starting things up, and he had a deep passion for China,” Avenues’s CEO told the Wall Street Journal when it reported Whittle’s resignation in 2015. This was polite speak for the belief that has dogged Whittle for most of his professional life: that he is Mr. Excitement in the blue sky stage but thereafter becomes either a nuisance or an outright menace.

The Whittle School is his rejoinder to the many skeptics and doubters. Even in hypercharged Beijing, Chris Whittle seems to dream at warp speed. “Oftentimes we tell him, ‘Slow down,’ ” says Yuan Bing. But time matters. Even if Whittle meets his target date of 2026, he will be nearly 80. “It’s inspiring,” he says, undaunted. “I’ve always worked hard, but now I work harder.”

This story appears in the August 2018 issue of Town & Country.

Subscribe Now

You Might Also Like