Chris Paul’s HBCU Bubble Looks Are More Than Fashion

When Darrell Armstrong spotted Chris Paul in the NBA bubble a few days ago, Armstrong told the Thunder point guard his play this season was MVP finalist-worthy, before pivoting to something he found even more impressive: a recent photo of Paul wearing customized Alabama A&M Jordans.

Armstrong, who enjoyed a 14-year NBA career and is now an assistant coach with the Dallas Mavericks, attended Fayetteville State University, one of just over 100 Historically Black Colleges and Universities still standing, and he had to let Paul know how grateful he was. “I told him I appreciate it,” Armstrong said. “We need support from...I don’t care who it is. We need support.”

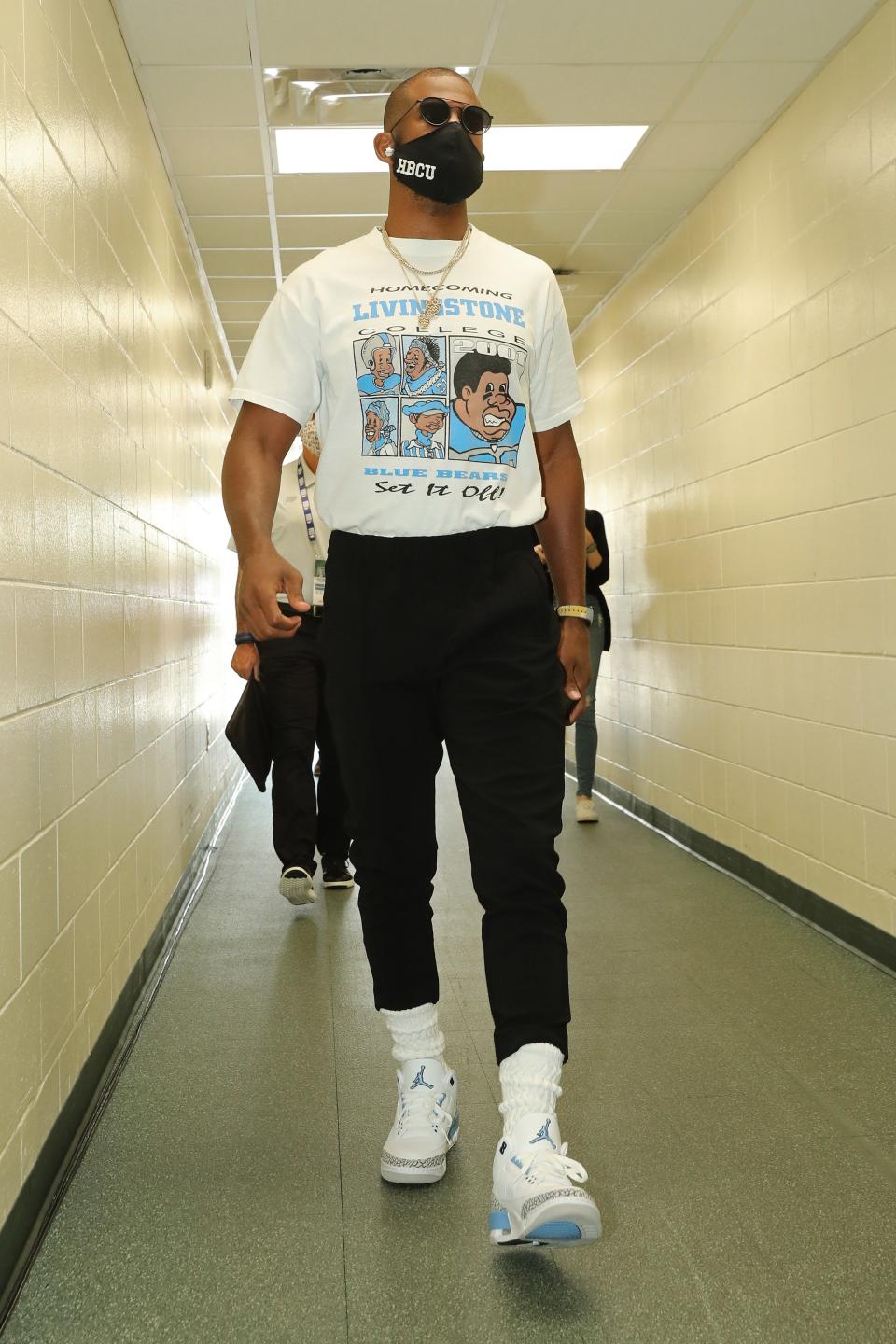

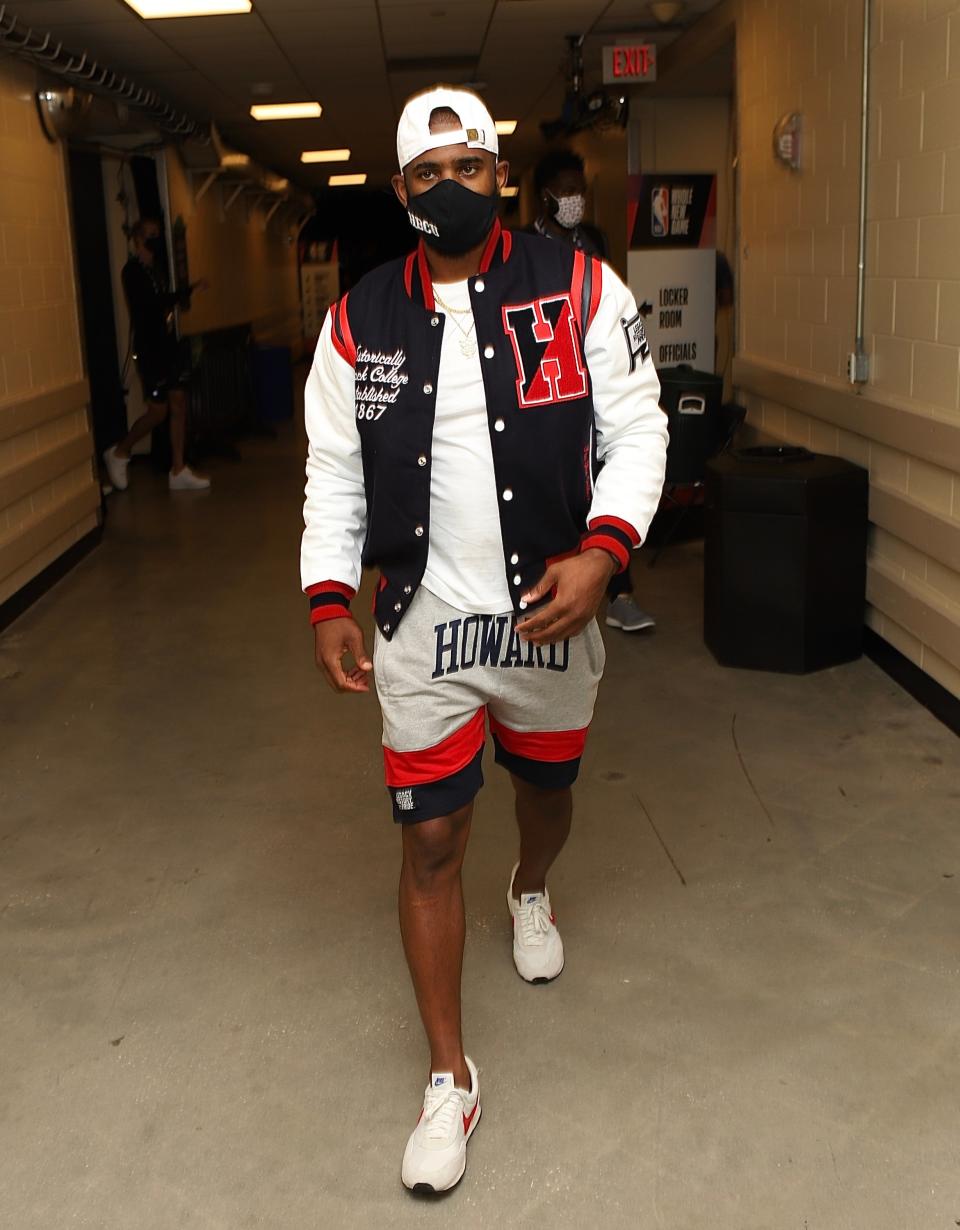

Paul has been providing that support since the 2018-19 season, when he strode into Houston’s Toyota Center on opening night wearing a grey hoodie that had “Texas Southern” painted across its front. In the bubble, he’s worked with personal stylist Courtney Mays to showcase different HBCUs in a more organized way. Support Black Colleges, a clothing line that was founded in 2012 by two Howard University students, has partnered with Paul to make Instagram posts with educational footnotes about whatever school he’s representing that day. Photos of Paul wearing, say, a Savannah State or Livingstone College t-shirt, have sparked anticipation about what’s coming next.

HBCU administrators have contacted Mays, and the rapper 2 Chainz reached out when he saw the Alabama A&M post, wanting to know when his alma mater Alabama State would get the spotlight. Thunder guard Devon Hall attended the University of Virginia, but keeps asking Paul when he’s going to wear something from Virginia State or Virginia Union.

HBCUs were founded after the Civil War to educate formerly enslaved Blacks who weren’t allowed entry into predominantly white public and private institutions during Reconstruction and the decades that followed. Today, as several face inadequate funding -- the most dire estimates forecast that only 35 HBCUs will still be around in 15 years --Paul wants to change the narrative that surrounds them.

“I definitely want to make sure I educate my kids on the importance of HBCUs and make sure they understand that they’re no less than any other school, a PWI (predominantly white institution),” Paul told me. “And I think that’s the perception that a lot of people have.”

The inspiration for Paul’s campaign began when Mays spotted the Texas Southern hoodie while strolling through the school’s nearby bookstore in search of a gift for her father (who attended Texas Southern University) and mother (who collects HBCU sweatshirts). “I went on campus to bring souvenirs home and just had this epiphany,” Mays said. “This is what we’re doing. I already had a look for him that was all-Black designer and was going in that direction and sort of said let’s do both. So that first look was probably the quintessential visual concept of what we were trying to do: Not only support Black designers and local designers but also amplify these universities that would not normally get the shine that they do now on the NBA stage.”

Mays grew up in Cleveland and graduated from the University of Michigan, but as a child she spent summers with her grandparents in Baton Rouge, a 10-minute walk from Southern University. She remembers the battle of the bands, and attending the Bayou Classic Thanksgiving football game between Southern and Grambling with her older sister. HBCU culture has always meant something to her.

“I think that HBCUs give an opportunity for Black students to be celebrated in a different way,” she said. “You are not looked at as a minority. You are a student, period. There’s not an uneven playing field amongst you and your white counterparts. You are told about your history in a way that’s authentic and genuine. You are celebrated professionals after you graduate. You’re given all the tools to be the best that you can be outside of your race.”

Paul went to Wake Forest, but has long shared Mays’ passion. His parents both attended Winston-Salem State University, and his wife’s parents went to West Virginia’s Bluefield State College (formerly known as Bluefield Colored Institute). As a high-school junior, Paul remembers watching his brother’s basketball games at Hampton University. The crowd had an energy he can only describe today as “different.” (Armstrong agrees: “If you do something spectacular, you dunk on somebody or block a shot, they cheer it. It don’t matter if you’re the home team or the away team.”)

Paul doesn’t lament his decision to play for a school that, at the time, increased his odds to make the NBA. But he wouldn’t mind seeing more top-shelf prospects in the future make a different decision.

“I’m not where I am today without my experience at Wake Forest,” Paul said. “But I was also lucky to be right down the street from Winston-Salem State University...Honestly, deep down inside, I wish I’d had an opportunity [to attend an HBCU]. They mean everything to me. I think that the funding, the facilities, the facilities when it comes to athletics, it’s one of the biggest things that has to change. When I was coming through high school and college we all thought that we had to go to these big schools to be seen to be showcased. But in today’s world with social media, if some of these kids got together and went to different HBCUs, imagine the attention that these schools would get.”

In order to increase that attention, Mays has acquired and customized countless HBCU items for Paul to wear. Usually she just calls up a school’s bookstore for their classic apparel, but now she gets requests: “My DMs are insane with people like ‘Hey I go to Cheyney University’ or ‘Hey I go to Spelman College, can I send you stuff’,” Mays said.

Since COVID-19, she’s had to get creative. “Some of it I’ve customized on my own, which I’m not really sure is legal because obviously I don’t have the licensing for it, but that’s a whole other thing,” Mays laughs. “I have a great embroidery team, and I’m creating graphics and using the logos and the messaging from the school in order to make a cool sweatshirt or a t-shirt or whatever it is.”

Before he went down to Florida for the NBA restart, Paul had eight gigantic duffel bags labeled and plastic-wrapped with every outfit he’d be wearing, down to his pajamas. “It was pretty intense,” Mays said. But even more shipments need to be made, and she’s in constant contact with Oklahoma City’s equipment manager in order to get Paul certain items. The one minor hitch is that packages sent to the bubble can’t be overnighted: There’s a cautionary sanitization process. “It’s a whole stressful system,” Mays said.

While in the bubble, Paul hopes to organize a call with players who’ve shown an interest in supporting HBCUs and improving their facilities. According to Mays, there’s also an apparel line in the works “to make sure every school has something that’s cool and has been curated by Chris and I.”

Paul is also set to produce a docuseries about the challenges HBCUs face when competing against PWIs in the world of sports-- everything from recruiting to the general allocation of resources. “We wanted to be able to tell the stories from their lens, through their eyes, and give people insight into what it’s like to be at an HBCU,” Paul said about the upcoming project.

“I don’t necessarily believe in segregation by any means,” Mays said. “But I do think that we should look to a Morehouse and say it’s just as good as a Michigan. We should look at FAMU (Florida A&M University) and say it’s just as good as a UPenn. As a Black person, if you choose to go to an HBCU you should know that you’re getting the same education that you would somewhere else.”

Despite declining enrollment numbers, according to the United Negro College Fund, as of 2015, 70 percent of Black doctors and dentists, half of all Black engineers and 35 percent of Black attorneys are HBCU graduates. Last year, the FUTURE Act was signed into law, guaranteeing permanent federal funding to HBCUs and other institutions that are largely minority. Several schools that were in danger of making severe budget cuts were spared. But a lot of damage has already been done. In the last two decades, several HBCUs have either lost accreditation or were forced to close, while more still find themselves in perilous situations. In 2012, 28,000 HBCU students were denied loans, resulting in a loss of approximately $155 million in revenue.

“I went to one of my little cousin’s graduations, from North Carolina Central,” Paul said. “And I was talking to someone about the funding and how a few HBCUs at the time were in the possibility of going under. And that’s always the case. Meanwhile, lo and behold, Senator Kamala Harris is the product of an HBCU. Howard University. So at some point change does occur. Why not now?”

Originally Appeared on GQ