A Chilling Batch of Evidence Could Revive the Unsolved Black Dahlia Murder Mystery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

On January 15, 1947, an aspiring 22-year-old actress named Elizabeth Short was found brutally murdered in a vacant lot near Leimert Park in Los Angeles, California, her nude, posed body cut in half and severely mutilated.

“It was pretty gruesome,” Brian Carr, a detective with the Los Angeles Police Department who worked on Short’s case, later said. It was an understatement; Short’s killer had also drained her corpse of blood and scrubbed it clean. “I just can’t imagine someone doing that to another human being.”

In the press, Short became known as “The Black Dahlia,” and her case “took on a life of its own,” Carr said. “Early on, I think for two months it was front-page news in all the local papers every day.”

Seventy-seven years later, while the Black Dahlia Murder may not be front-page news, it’s still generating new true-crime investigations, fictionalized retellings, and even grisly in-person tours of the victim’s final known locations. That’s because the Black Dahlia’s killer was never found, and no one has satisfactorily offered proof for who committed the most infamous, sadistic act of unsolved murder in Hollywood history.

But people are still searching for that answer. And now, more than three-quarters of a century later, time might help us finally find it.

Who Was Elizabeth Short?

Before she was The Black Dahlia, she was Elizabeth Short. She was born July 29, 1924, in Massachusetts, to parents Cleo and Phoebe Mae Short. As a young girl in Medford, Biography notes, her imagination was kindled by motion pictures. In Black Dahlia, Red Rose: The Crime, Corruption, and Cover-Up of America’s Greatest Unsolved Murder, Piu Eatwell writes that Short and her fellow schoolgirls went and saw the latest movies and reenacted their favorite scenes. Short did so with such flair and passion that she was frequently compared to actress Deanna Durbin, a popular teen star in the 1930s.

It might sound like Elizabeth Short was destined for Hollywood, but her journey was far from straightforward and had its share of hardships. At the age of 18, she first moved to California to live with her father, who had earlier left her family to start a new life on the west coast. Following a disagreement, she got involved with an Air Force sergeant at Camp Cook who, according to Brenda Haugen’s Black Dahlia: Shattered Dreams, was abusive to her.

After Short was arrested for underage drinking in 1943, she landed in Florida, where she met Major Matthew Michael Gordon Jr. She reportedly agreed to marry Gordon, but tragically, he died in a plane crash in August 1945, before they could tie the knot. Although Gordon’s mother later claimed that her son and Short were never engaged, this came out only after Short’s death, by which time her reputation had already been damaged in the intense media scrutiny that followed.

Following this tragic loss, Short set out for Los Angeles, hoping to start over in the world of Hollywood.

What Was Hollywood Like During the Black Dahlia Murder?

It’s easy to compare any unruly place and era to the “Wild West,” but for all of its neon signs and towering skyscrapers, the Los Angeles of the 1940s wasn’t that far removed from the real Wild West.

Legendary figures like Elfego Baca, a famed Western lawman, were still around when Major Gordon Jr.’s plane crashed. John Reynolds Hughes, a Texas Ranger believed to have inspired the “Lone Ranger” character, even lived longer than Elizabeth Short. And some LAPD officers on the force for less than 20 years might have had the chance to meet Wyatt Earp, an iconic figure of the Wild West, who spent his last days in an L.A. bungalow.

Some of the Wild West’s spirit still lingered in 1940s Los Angeles. There was a sense that certain authorities overlooked illegal activities, influential men used their power for corrupt purposes, and journalists were always looking to add some extra excitement to their stories for the readers.

But the kind of heroic cowboys of the old West—who stood up for the weak, fought for justice, and always caught the bad guy—were now relegated exclusively to the Hollywood sound stages, in films like My Darling Clementine, which debuted in Short’s final month of life.

Ever the film fan, perhaps Short even saw the Western, play-acting in her mind the role of Chihuahua, the hot-tempered love interest of the famous “Doc” Holliday. In a particularly gruesome scene for its day, the shaky hand of the alcoholic Holliday has to perform surgery without sedation on the wounded Chihuahua, who ultimately succumbs to her injuries. In a wide shot, the audience can hear her cry, “Oh ma!” as the surgeon’s blade pierces her.

How Did Elizabeth Short Die?

“Only a surgeon could have killed her.”

That was the assessment made, before Short’s brutally desecrated corpse had even been identified. A surgeon did it. Or a doctor. Or, at the the very least, someone who had medical training. (Helena Katz’s Cold Cases reveals the LAPD was so convinced of this fact that it conducted background checks of the entire student body of nearby USC Medical School.) This was the only way to explain the transparent precision of the perverse mutilation of Short’s corpse.

At around 10 a.m. on January 15, 1947, a local female resident found Short’s nude, bisected body lying just off the sidewalk. Her stark, white skin was “offset by jet-black hair,” according to Biography. Her body was pale partly because it had been carefully cleaned and drained of blood. Short’s killer also carved a smile into her face by cutting the sides of her mouth, making it clear the corpse hadn’t merely been defiled after death—it had been prepared to be discovered.

Short’s body was even found carefully posed, her upper half with arms raised above her head, reminiscent of surrealist artist Man Ray’s 1934 photograph “Minotaur.” (Books like Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia have drawn numerous comparisons between the corpse’s state and the surrealist art of the time.)

Short’s face, beyond the mouth cuts, was still clearly visible, albeit with injuries consistent with “repeated blows.” And though the LAPD of the 1940s didn’t have the modern tools of DNA testing, police were able to procure fingerprints from the corpse.

As Biography notes, “...an editor at the Examiner suggested sending fingerprints via the paper’s ‘Soundphoto’— an early fax machine—to an office in Washington, D.C., where they could be relayed to the FBI.” By the evening of January 16, authorities had matched the prints to those of 22-year-old Elizabeth Short, who had previously been fingerprinted during her underage drinking arrest.

How Did Elizabeth Short Become The Black Dahlia?

The press had identified the victim, but they were hungry for more. As both Haugen and Eatwell describe, one reporter sought extra details by reaching out to Short’s mother, Phoebe. The reporter misled her, claiming Short had “won a beauty contest” and they needed background information for their coverage. It was only after Phoebe provided all the details they sought that the reporters disclosed the tragic news of her daughter’s death.

It was now time to turn Elizabeth Short from a crime statistic into a sensation.

The initial nickname given in connection to the crime referred to the unidentified assailant as “The Werewolf Killer.” However, this moniker didn’t last. It might have been because the werewolf reference lacked specificity or intrigue. Or maybe because, by then, werewolves had lost their appeal in Hollywood, with the Wolfman being overshadowed by other iconic monsters in movies like House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula.

But one reporter got wind of a nickname Short had allegedly picked up in Long Beach. According to Biography, “the victim was known among acquaintances there as the ‘Black Dahlia,’ a nod to her taste for black dresses and the previous year’s crime film, The Blue Dahlia.” But in that movie, nobody meets the gruesome end that Elizabeth Short suffered—such graphic depictions wouldn’t have passed the censorship rules of the Hayes Code, a set of moral guidelines for what was acceptable content in American movies, and it’s doubtful that studio personnel would have tolerated it either.

The most notable connection between Short and The Blue Dahlia is the shared life parallels with the film’s leading lady, Veronica Lake. Both women were born on the East Coast, and both moved to Florida before making the pivotal move to Hollywood. And weirdly, both had lived with people with the last name Toth: Lake was briefly married to director Andre de Toth, while Short roomed with Ann Toth, who would later become an important witness in the investigation of her death.

And both Short and Lake were turned into “sex symbols” by the denizens of Los Angeles. Lake, however, dismissed the tag assigned to her by the Hollywood media, preferring to characterize herself as more of a “sex zombie.”

Short, naturally, wasn’t able to challenge the labels the press gave her. After her murder, the story changed from depicting her as a naive dreamer heading to Hollywood, to a portrayal of a “fast girl” with loose morals. She was someone who was seen around town, potentially a prostitute, and in a tantalizing twist for the 1940s media, there were even suggestions that she might have been a lesbian. (Despite the fact that the theory claiming Short was killed as part of a “lesbian love triangle” was disproven in front of the Los Angeles County grand jury, this didn’t prevent the newspapers from sensationalizing the idea and exploiting the fear surrounding homosexuality at the time.)

How Did Police Hunt for the Black Dahlia’s Killer?

The press and the police meticulously analyzed every detail of Short’s life. They initially interrogated Robert “Red” Manley, a married man who had an affair with Short and was the last known person to see her after dropping her off at the Biltmore Hotel on January 9. While his alibi held up, and Manley was exonerated of any suspicion, his affair with Short became headline fodder for every Los Angeles newspaper.

Then came a moment that, in a Hollywood picture, would have been the Act II breakthrough that would have blown the whole case wide open. Biography writes:

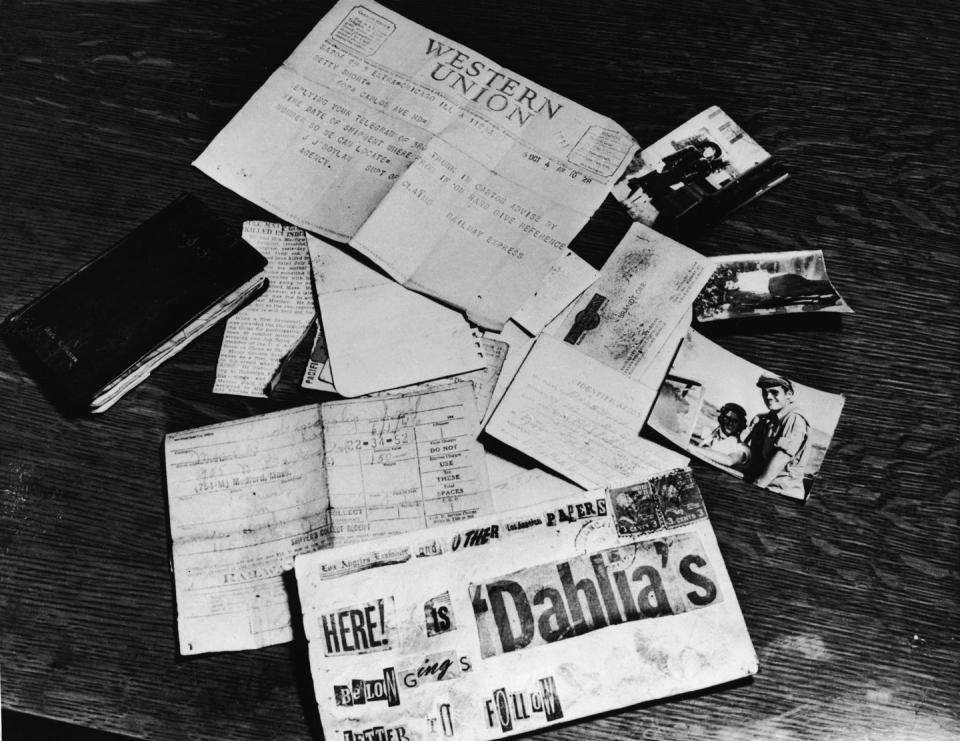

“In late January, an envelope labeled with cut-out words and the phrase 'Heaven is Here!' arrived at the Examiner's office. Inside was a collection of Short's personal documents, including her birth certificate, Social Security card and an address book featuring the name 'Mark Hansen' on the cover.”

But real life in L.A. didn’t work out like the movies. Police “...tracked down approximately 75 men from the book, most of whom had only briefly met its owner, as well as Hansen, a successful nightclub owner.” More letters containing cut-out words arrived, mocking law enforcement, but none were definitively linked to the actual killer. Both men and women came forward with confessions to the Black Dahlia murder, but consistently provided incorrect details under questioning.

And in 1949, a scandal involving coerced confessions sparked public outrage and possibly led to a diminished intensity in the once unyielding hunt for the murderer.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t still prominent suspects.

Who Killed the Black Dahlia?

At the height of the Black Dahlia Murder investigation, police considered a myriad of suspects, and amateur sleuths have continued to delve into LAPD records and personal archives seeking new insights. However, these independent investigations often give rise to far-fetched theories attempting to weave every unconventional notion into a tidy, conclusive package.

In the whirlwind of investigative journalism, books, and podcasts, names that were once prominent in the daily newspapers, such as Mark Hansen (linked by the address book) and Leslie Dillon (caught up in the “false confession” scandal) now find company with, or are sometimes implicated alongside, newer suspects.

Amateur sleuths have taken a keen interest in Dr. Patrick S. O’Reilly, a surgeon and acquaintance of Hansen, who appeared on a 1951 list of suspects. They’ve been actively probing deeper into his background for further information, discovering that not only did O’Reilly allegedly beat his secretary nearly to death “for no other reason than to satisfy his sexual desires without intercourse,” according to Los Angeles district attorney files, but that “O’Reilly” wasn’t even his real name; there’s allegedly no evidence that the sadistic surgeon existed before 1924.

Meanwhile, in The Black Dahlia Files: The Mob, the Mogul, and the Murder That Transfixed Los Angeles, Donald H. Wolfe presents a theory that involves both Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler and infamous mobster Bugsy Siegel.

Given the Black Dahlia murder’s Hollywood backdrop, some people have speculated that the killer must have been a celebrity. Mary Pacios, who grew up with Elizabeth Short, believed that actor and filmmaker Orson Welles was responsible, suggesting that he had a “diphasic personality” that could lead to violent acts, and even alleging that Welles concealed clues about the crime in his movie The Lady from Shanghai.

Folk singer Woody Guthrie was also questioned in the Black Dahlia murder investigation, due to obscene sexual letters he had been mailing to other women during a mental health episode, according to Black Dahlia, Red Rose.

The Black Dahlia Files notes that the LAPD questioned comic actor Arthur Lake, who starred in the Blondie film series, regarding both the Black Dahlia murder and the 1944 killing of oil heiress Georgette Bauerdorf in her Los Angeles apartment. It was theorized that Lake might have known both women through the Hollywood Canteen, a club for servicemen that Hollywood celebrities sometimes helped run. However, whether it was the LAPD at the time or the author of The Black Dahlia Files, there was a discrepancy in the timeline: the Hollywood Canteen closed in November 1945, and Elizabeth Short didn’t arrive in Los Angeles until July 1946.

Today, the most prominent suspect in the Black Dahlia murder is Dr. George Hodel, thanks to books, podcasts, and even a television series. Implicated by his own son, former LAPD detective Steve Hodel, in his book Black Dahlia Avenger: The True Story, George Hodel was a Hollywood doctor with prominent friends like director John Huston and the artist Man Ray.

Hodel became a suspect in the Black Dahlia investigation in 1949, after he’d stood trial for sexually assaulting his own daughter. (Hodel was acquitted.) The doctor found out that the LAPD had even taken the step of placing a wiretap in his home. The transcripts from these recordings captured Hodel saying, “Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They can’t prove it now.”

Steve Hodel’s theory has resulted in several books, as well as the TNT television series I Am the Night and its companion podcast Root of Evil. But not everyone is sold on Steve Hodel’s assertions. “Fellow researcher Larry Harnisch poked holes in his assessments,” Biography notes, “...and Hodel’s credibility took a hit when he also claimed that his dad was the Zodiac Killer.”

Will the Black Dahlia Murder Ever Be Solved?

New possible evidence keeps emerging in the Black Dahlia case. In 2018, a woman named Sandi Nichols uncovered a letter her grandfather, a former police informant, wrote in 1949 that asserted the Black Dahlia was killed by a man named “GH,” adding fuel to the George Hodel fire.

Steve Hodel and other amateur investigators continue to uncover information once held secret as the people protected by those secrets die off. After all, there’s little impetus to protect their fading reputations much longer.

Ultimately, the Black Dahlia murder is far more likely to be solved than that of Georgette Bauerdorf, or the stacks of unsolved murders within the LAPD’s cold case files. And that’s because we all still know the name The Black Dahlia.

The media aimed to sensationalize Elizabeth Short’s murder, portraying it as a symbol of a city lost to chaos—a “werewolf” slaying of a woman tagged with the name from a 1946 noir film that would fade from memory. Yet, it’s this very sensationalism that has kept interest in the case alive, prompting the public to relentlessly pursue justice for the Black Dahlia, unlike the many other unsolved murders that have been relegated to old newspapers and the backlog of cold cases.

And as long as people keep looking, digging, and uncovering, amidst all the personal grievances and outlandish theories, the answer may finally emerge.

You Might Also Like