Chicago’s Real Signature Pizza Is Crispy, Crunchy, and Nothing Like Deep Dish

I grew up knowing the Chicagoland suburb of Northbrook for a few things: its pee-wee hockey team, bar mitzvahs, and the pizza at Barnaby’s. When I recently found myself in the neighborhood at 5:30 on a Friday night, hungry and without dinner plans, I decided to stop into the popular local restaurant on my way back to the city. Not taking into account it was the start of the weekend, I drove around the small parking lot for ten minutes before a spot opened up. When I finally sat down among the birthday parties and family dinners, and my pizza made it to my table, I did what many of us tend to do these days: I Instagrammed my meal. A few minutes later I checked my comments and saw a response posted from a friend in Brooklyn: “Is that the way Chicago pizza is sliced? That is insanity.”

I could have been offended, but I wasn’t. Instead, I took it as a small win for the Chicagoland area’s underappreciated contribution to the American pizza map: A circular pie with really thin crust, all cut into tiny squares. Some call it “party cut,” others say it’s “tavern style,” but to locals, it’s just “pizza.” Ask around, and most Chicagoans will tell you that the city’s greatest pies aren’t made in deep pans drowning in layers of cheese and meat at tourist traps like Uno and Lou Malnati’s. Yet, for some reason, people outside the city hardly seem to know the style even exists.

“It’s an original Chicago creation,” boasts Steve Dolinsky, Chicago food writer, television personality, and author of the book Pizza City, USA. “You have a beer in one hand and something to eat in the other. It’s a product of convenience. Something you don’t fill up on, so you can get home and eat a real dinner.” This explains one theory for the moniker “tavern style,” named for those pre–smoking ban rooms populated by working-class immigrants unwinding after a shift—spaces where neon signs, red plastic pitchers of watery beer, and thin-pies put out as a cheap snack to munch on (and as an encouragement to keep drinking) were all standard fare. More than a half century later, these taverns are still the best places to get a truly good Chicago pie, nestled in the same spots since they first cranked up their ovens.

Take Vito & Nick’s, arguably the first—and certainly the longest standing place (vouched for by Dolinsky and Chicago Pizza Tours founder Jonathan Porter)—to offer up Chicago-style thin crust. Third-generation owner Rose Barraco George believes it was her father, Nick Barraco, who originally cut the restaurant’s first pies into squares when they added them in 1946, the year he returned from World War II to take over the business opened by his parents, Sicilian immigrants Vito and Mary Barraco, in 1923. The prices were low, the experience casual. “You ate it on a napkin,” George says of the pizza. Today’s recipe is the same one George’s grandmother created over 70 years ago.

Soon after, other South Side places like Home Run Inn and Italian Fiesta Pizzeria started introducing their own takes on the thin-crust style, and things took off from there.

There are no laws governing the tavern-style recipe, so every place makes it differently. Ask most of the people who make it, and they’ll tell you the desired outcome is often described as “cracker crust.” I’ve described it as a texture with the same snap as matzah, but without the cardboard taste and unforgiving mouthfeel. This is pizza we’re talking about; it shouldn’t be a crust of affliction.

Barnaby’s, for all its sustained success, is sort of an outlier in this respect. The crust on its pizzas isn’t crispy; it looks more like a pie crust and is chewier than you’ll find in most places. Opening in the South Loop in 2010, Flo & Santos is a relative newcomer to the tavern-style game but has one of the best distributions of give and take I’ve had: The middle pieces have some chew and are topped generously (but not too generously) with sauce and cheese, while the outer parts have the right amount of crackle. Executive chef Mark Rimkus says his dough sits anywhere from 24 to 48 hours to achieve that perfect flatness and then gets cooked at 600 degrees. Rimkus, who was raised on the South Side, says his pizzas fit somewhere between Vito & Nick’s, “just not as thin,” and another local institution, Palermo’s of 63rd, “just not as thick.”

Porter claims that getting the mozzarella from the Mancuso family in Joliet is “essential.” Some restaurants boast of using organic tomatoes in their homemade sauce, while others rely on cans of Stanislaus. Most agree that the sausage, another point of Chicago pride, must come as little hand-rolled gobs with bits of charred fennel seed. (Many tavern pies only have a single topping so the thin crust won’t break under the weight.) George proudly states that Vito & Nick’s has been sourcing its ingredients from the same local family purveyors for as long as the pizzeria has been around. “I only use small independent businesses. They’re not going to change; their name is on that product,” she says. “With big companies, you become a number.”

Then there’s the oven: Most places use the very unsexy stainless-steel deck ovens that usually cook with gas or electricity—a very practical, get-the-job-done-right appliance. “That has a real big impact on the flavor and how the pizza comes out,” says Pat Fowler, co-owner and general manager of Candlelite, a Rogers Park institution since 1950. His pizzas are crunchy, with mozzarella cheese toasted orange and gold in the style of an Impressionist’s painting of an autumn day. It’s delicious, but there’s no real showmanship involved in its making—no big fires or smell of burning wood in the air.

But the thing that most defines tavern style is the cut: small, uneven square slices, along with four little witch hat–shaped triangles at the corners. Dolinsky says the term “party cut” comes from the fact that the manageable portions make it a popular choice for the petite hands at kids’ birthday parties. It sounds nice and simple, but some believe that the pie’s unconventional shape actually has something to do with why it never caught on as Chicago’s signature pizza.

“It’s counterintuitive,” says Chicago-born chef and restaurateur Dale Talde. “Chefs try to make things equal,” and most tavern-style pizzas come out anything but. Chef and writer Amy Thielen echoes a similar sentiment. “The square-cut shape is its downfall,” she says. “When you think of pizza, you think of an iconic triangle shape. You don’t think of a square.”

Its general unsexiness likely isn’t helped by its humble history—first as a cheap, easy snack among hard-working blue collars, and later an easy solve for feeding small, fidgety bodies. It might have been a popular choice, but there wasn’t much glamour to work with.

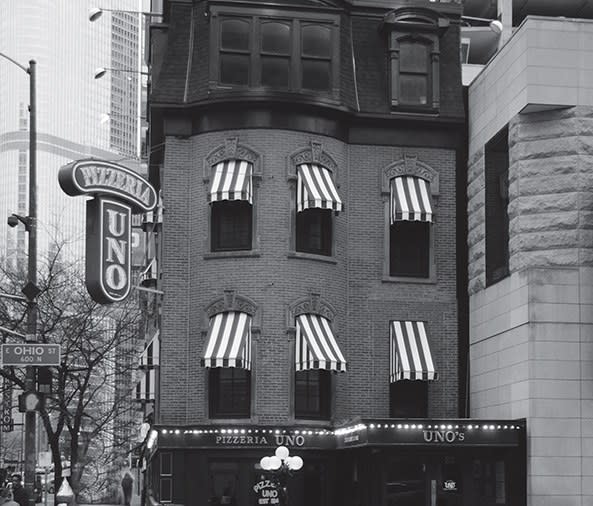

But that still doesn’t explain how deep dish became synonymous with Chicago. Legend, albeit a contested one, has it that in 1943, Ike Sewell, a Texas-born former college football star and founder of Pizzeria Uno (originally called The Pizzeria), initially aimed to bring Tex-Mex to the city. His chef, Rudy Malnati, delivered a recipe for this newfangled pizza instead, and the former All-American Sewell stood outside handing out free slices just the same. The pizza was popular enough that Sewell and his partner, Ric Riccardo, were able to open a second location, Pizzeria Due, a few blocks away in 1955.

But what really tipped the balance was a supposed newspaper article that—as Porter puts it—“nobody can seem to find.” (I tried; I couldn’t either.) The myth goes that a writer who’d served in Italy during World War II claimed he’d never had a better pie than the original Uno deep dish. That one statement alone linked the style (and the pizzeria) to Chicago, and lodged it in the American conscience as a pie worth trying.

Over the next several decades, Uno inspired a wave of imitators: Gino’s East in 1966, Lou Malnati’s (Rudy’s son) in 1971, Pequod’s in the suburb of Morton Grove that same year. Chicago-style deep dish even made its way into cookbooks as an alternative to the traditional casserole, which some might say has more in common with deep dish than actual pizza

Chicago-Pizza-Uno-Pizzeria-1943.jpg

Though they arguably had a head start on Sewell and Malnati’s creation, the thin-crust, square-cut pies of places like Vito & Nick’s didn’t achieve the same level of fandom. (Part of that might be due to the fact that it shares similarities with other nascent midwestern pizza styles of the time, including St. Louis style pizza, started in 1947 by Amedeo Fiore, who had moved from Chicago in the 1930s.) The party-cut pies could never catch up to the deep-dish boom.

Barnaby’s, which opened its first location in 1969, billing itself as a “come as you are” place with “an informal old English pub atmosphere,” attempted expansion into other states like Indiana, Wisconsin, Missouri, Virginia, and Florida in the mid-70s, only to see many of its franchises close by the end of the next decade. The reasons were varied but competition with the proliferation of national chains like Pizza Hut, Little Caesars, and Domino’s, not to mention family-friendly places like Chuck E. Cheese’s didn’t help. In the years since, very few new places have opened making tavern style—and even fewer of them have been that good.

But that doesn’t change its standing among true Chicago pizza appreciators. “We own this,” chef Dale Talde says with the pride of a Chicagoan who loves to remind you how many championships Michael Jordan won with the Bulls. “When people talk about cheesesteaks in Philly, it’s always the people who aren’t from Philly that try to tell you where to go eat a good cheesesteak. Everyone in Philly will go, ‘Yeah, you go eat at Pat’s or Geno’s if you want. Go wait in line like all the other schmucks because I’m going to John’s Roast Pork.’ I’ll let all the tourists eat at Lou Malnati’s and Gino’s East; I’m gonna go to Barnaby’s.”

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit