Chelsea Boes: Remembering Asheville's Wilma Dykeman and her love of the French Broad River

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In late February, I found on my desk a slim white envelope addressed to me. Inside was a press release for a picture book called "Of Words and Water: The Story of Wilma Dykeman — Writer, Historian, Environmentalist," by Shannon Hitchcock.

I emailed the author to ask if she meant to send this envelope here, to me, at WORLD Magazine headquarters. (I work as a book reviewer and children’s editor at this Christian magazine. But since her subject matter is Asheville-specific, it seemed more likely that Hitchcock had found me through the Citizen Times.)

She answered almost immediately:

Hi Chelsea,

Honestly, I don’t know! Jim Stokely gave me your name and contact information as someone who might be interested in my forthcoming book about his mother. It’s not a religious book, but its message is, “Be good to the earth, kind to other people, use words to fight injustice.”

Thanks,

Shannon.

It was all like a strange game of telephone, since before that moment I had never heard of Jim Stokely.

A fat, manila envelope arrived shortly after: the advance review copy. I read it at my desk in blissful silence: “Born in the Blue Ridge Mountains/ near the French Broad River,/ Wilma Dykeman was an only child. Her first words were — ‘Water coming down.’” Sophie Page’s mixed-media illustrations show this baby Wilma as a rosy-cheeked child of clay, dipping white legs into clear water populated with crayfish and lizards.

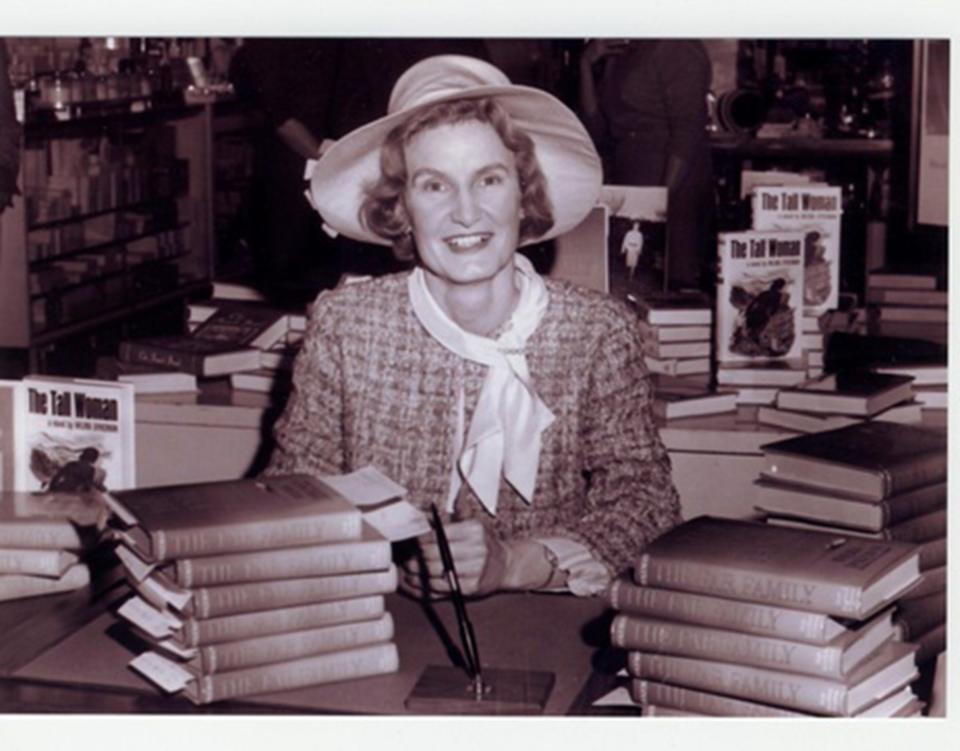

Wilma learns to love river and words, earns a scholarship for school, marries James Stokely, builds a stone cottage in the Smoky Mountains. “James became her research partner,” Hitchcock writes. “Together they journeyed along the French Broad River collecting stories from local families.” Wilma exposes companies and towns for dumping waste into the river. She becomes a newspaper columnist and her messages are “as constant as rivers rolling toward the sea.”

From the backflap I learned that Wilma, just like me, was born to an upstate New York farmer. I learned that her book about Asheville’s French Broad River came out years before Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking "Silent Spring" and that both books helped lead to the creation of the EPA.

In April, among haunted mannequins at Sweeten Creek Antiques & Collectibles, I found a fat green copy of Wilma’s book "The French Broad." I toted it with me through the store stuffed with Tupperware bowls, Beethoven busts and dusty vinyl records in pilling paper sleeves. With her peculiar staying power, Wilma felt misplaced here. At the checkout, the cashier and a patron chatted about Wilma when they saw the book.

“She lived here,” said the patron.

The cashier eyed the volume. “And she had something to do with the trails.”

The patron leaned against the counter. “The French Broad flows north!”

I wondered: Was that why New-York-descended Wilma liked it so much?

It was too late to ask Wilma this, of course — since, as per the "Of Words and Water" backflap, she died in 2006 at the age of 86.

But it wasn’t too late to go back and read what she wrote about our river.

At home in my hammock I cracked open "The French Broad." The writing, to my delight, felt more bucolic than environmental: Rather than centering mainly on an unpeopled landscape a la Thoreau, Wilma was talking about the people who nurture the river — the people Sophie Page rightly represented with a little clay-faced man perched on a dock holding a baby. Wilma was speaking through the voices of mountain people. She talked about the zoological diversity of this region because here species of North and South overlap. Then Wilma dropped the mic: “It is not such a startling marriage of opposites to shift from the smallest to what we call the highest form of life on the river — from its salamanders to its people. For the people too are richly varied, rare and worthy of attention.”

I also took "Of Words and Water" home to read to my little ones. Why not have a new book about Wilma now, not for grownups but for little children? “It is easy to destroy overnight treasures that cannot be replaced in a generation,” Wilma wrote in "The French Broad." She said it’s “easy to destroy in a generation that which cannot be restored in centuries.”

Wilma reminds us that a river is a real historical gift. And Hitchcock’s new book tells little girls and boys in our mountains that they can do as Wilma did — love something good and fight for it with well-chosen words. “The landscape changes,” Wilma wrote. “The mountains remain.” And that’s more religious than it seems. My little girls live in these mountains. It’s a very religious idea that the stewardship of creation — not all creation but this creation — will fall to them.

I should mention: At the time of my visit, Sweeten Creek Antiques & Collectibles also had a lovely yellow hardcover of "The French Broad" inscribed by Wilma herself. Maybe it’s still there. Maybe you should go buy it.

Chelsea Boes lives in Old Fort and works as editor of WORLDkids Magazine in Biltmore Village.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Chelsea Boes: Remembering Asheville environmentalist Wilma Dykeman