How Chef Kwame Onwuachi Used His Bronx Upbringing to Create One of N.Y.C.’s Best Restaurants

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kwame Onwuachi will be the first to tell you that he was a terrible barista. He could never get the latte art right when he manned the espresso machine at Craft, Tom Colicchio’s flagship Manhattan restaurant, in 2010. But as staff trickle into Tatiana, the glitzy restaurant he opened in Lincoln Center’s David Geffen Hall in November, he expertly pulls an espresso—though he doesn’t bother to foam the milk, having yet to master the technique of drawing pretty designs in it.

Onwuachi has overcome far more consequential failures in his 33 years than messing up a cup of coffee. He had a drug problem as a youth, and his first, much-anticipated restaurant was a huge washout. But just a few years later, he has bounced back to become one of the most acclaimed chefs in the country.

More from Robb Report

The Owners of the Mets and Hard Rock Want to Build an $8 Billion Casino in New York

This Oldest Michelin-Starred Restaurant in Belfast Is Closing Because of Soaring Costs

Lil Yachty Paired a Preppy Thom Browne Look With a Rare Patek Philippe for the CFDA Awards

Tatiana has landed on a swath of best-new-restaurant lists (including in this magazine), and in April The New York Times food critic Pete Wells ranked it No. 1 on his 100 Best Restaurants in New York City. It would be disingenuous, though, to suggest that Onwuachi has been an overnight sensation. He made a big impression as a contestant on Top Chef’s 13th season in 2015 and did a stint as a judge on the Bravo show a few years later. His awards are plentiful, among them the James Beard Foundation’s 2019 Rising Star Chef of the Year. His 2019 memoir, Notes From a Young Black Chef, was a bestseller and is currently being made into a movie, and he finished writing a cookbook, My America: Recipes From a Young Black Chef, during the pandemic. Speaking of which, when Covid brought the restaurant industry to its knees, he took a nearly yearlong private-chef gig with Rihanna, established the Kwame Onwuachi Scholarship Fund at the Culinary Institute of America (his alma mater), and negotiated the terms of Tatiana with the Lincoln Center board over Zoom.

But to Onwuachi, none of that defines success.

“To me, success means being able to do the thing that I love, day in and day out, and make a living off of it,” he says. “It’s so simple. When I was a line cook, I felt I was successful. Success isn’t a dollar amount or an award. Those things are just superficial.”

Onwuachi’s path to high-end dining was not clearly marked—if it was marked at all. He was raised in the Bronx mostly by his mother, Jewel Robinson, who recruited him in the kitchen to help with her catering company. But he sometimes stayed with his father, whom he describes as abusive. Though bright—he was placed in gifted-and-talented classes—Onwuachi had behavioral issues and was labeled a troublemaker early on. In his memoir, he recounts pushing a boy off a jungle gym (the child broke his wrist) and being hauled to the principal’s office for swearing when he was only in second grade. But he was also driven.

“Kwame always thought he’d be a millionaire by the time he was 18,” Robinson says from New Orleans, where she now lives. “When he turned 18 and hadn’t earned his first million, he thought his life was over. There was no failing in Kwame’s world.”

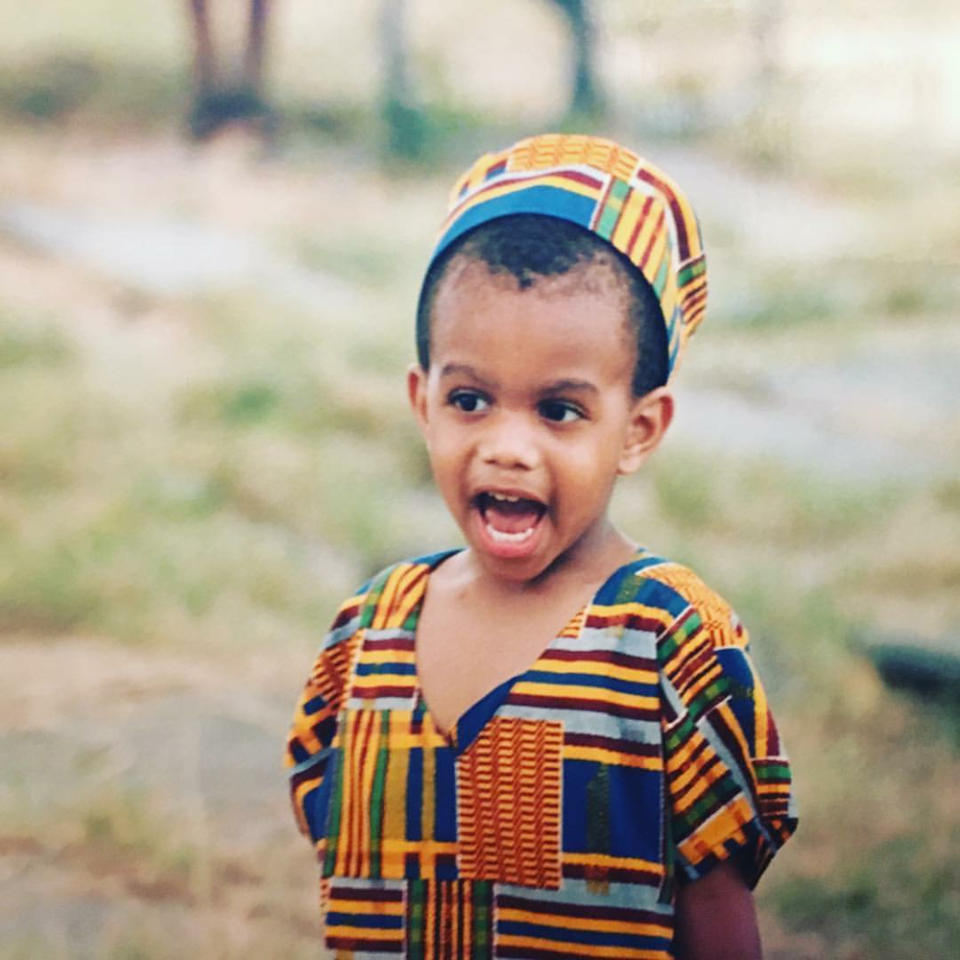

After catching him in too many lies, Robinson sent her son to live in Nigeria with his paternal grandfather, Nigerian-born anthropologist Chike Onwuachi-Obi, a retired professor of Pan-African studies at Howard University. Onwuachi was 10. He lived in a village where the electricity “kinda came on when it felt like it,” he recalls. What was supposed to be a two-month stay became a two-year immersion in his heritage—and propelled his life’s work.

“It directly correlated to my craft,” he says now. “I raised my own chickens and livestock. A deep respect I have for what we eat was birthed there, as well. Not everything comes in a cellophane package—there’s a life associated with it.” He has spoken of getting teary-eyed when, on his return to New York City, his mother took him to KFC and he contemplated the lives of birds destined for fast food.

His grandfather’s influence is also well evident. Over the years—and especially at Tatiana—Onwuachi has approached cooking through an anthropological lens. With a menu composed of fine-dining riffs on foods that shaped him, Tatiana is an edible, sensorial autobiography that alludes to New Orleans, Jamaica, and Africa. There’s also the much-buzzed-about high-end take on the chopped-cheese sandwich, a Bronx-bodega staple, which he makes with aged rib eye, smoked mozzarella, and Taleggio on brioche, topped with shaved truffle.

“You can learn a lot about culture through food and the dishes that have stood the test of time,” he says. “They’re snapshots of history, and they really tell a story. It wasn’t someone trying to become famous; it’s just using what was available. I love breaking down dishes based on ingredients that were there. You can tell who passed through those places.”

Onwuachi learned his cultural heritage from family, but he picked up some of his business savvy selling drugs on the streets of the Bronx and as a student at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut, where he ran a sophisticated—and lucrative—operation from his dorm room. The enterprise fed a drug habit of his own, and he was kicked out of university housing after being caught smoking weed and failing a drug test. Living off campus, he graduated from cannabis to pills, and he ended up dropping out of school. He felt immortal, he writes in his memoir—until he crashed.

What he calls his “come-to-Jesus moment” arrived after Barack Obama was elected president in 2008. Onwuachi was hungover from an epic bender but says, “It was a moment of clarity. Here was a Black man about to hold the highest office in the world. I realized I could do anything I put my mind to.” He flushed the drugs down the toilet, went out and bought ingredients for chicken curry, and made the decision to heed his calling.

He’d begun learning the necessary skills for managing a kitchen when he was 16 and went to work for McDonald’s. “It was exciting, fast-paced, and if you really listen to their values and what they try to do, it sets the groundwork for organization: I learned how to clean a walk-in because of them; I’m a really good expediter because of them,” he says. “People give McDonald’s a bad rap, but they’re the most successful restaurant in the world. If you pay attention to their business model, it’s pretty fascinating. They know how to effectively get things done.”

But his entrepreneurial boot camp was in selling: first drugs, then sweets—and not the artisanal kind. When he was 20, after a stint in Louisiana cooking for the Deepwater Horizon oil-spill cleanup crew, he returned home and started hawking mass-market candy—“lots and lots of candy,” he says—on the subway, a classic New York City hustle. (A tattoo illustrating himself in action is one of many references to his past and heritage covering his arms.) He netted about $20,000 in two months. In a prescient twist, he used to peddle his wares around the Lincoln Center station. He even snuck into the James Beard Awards ceremony one year, just to take in the flashy scene in the very lobby that Tatiana now occupies. Remembering how much he enjoyed cooking with his mom as a kid, he pledged to himself he’d return—by invitation.

Onwuachi funneled the cash he earned into a start-up catering business. Knowing that he needed technical skills, he enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America (CIA), and doors flew open. In 2012, he gave a speech at a CIA awards ceremony in Manhattan and caught the eye of Daniel Humm, who invited him to intern at Eleven Madison Park. There, he met James Kent, the chef who ran the kitchen. Kent immediately felt a kinship as a fellow New York City kid.

“There’s something about him: When you grow up in the city, you have this grind,” says Kent, now chef-owner of Saga Hospitality Group, which operates Overstory and the two-Michelin-starred Saga. “He’s a young Black kid from the Bronx working in the fine-dining world. I love it—I want to give this guy as much support as I can. It’s not like he just rolled up. He hustled.” Kent offered Onwuachi a job as a line cook at Eleven Madison, where he spent a couple of months commuting from CIA’s upstate campus a few days a week. For an externship at Thomas Keller’s Per Se, he moved back to the city and lived with his sister, Tatiana (his restaurant’s namesake), earning extra cash by showing up at the Food Network at 6 a.m., ready to leap in as an understudy chef. During his time at these restaurants, he analyzed the technical aspects of high-pressure kitchens with scholarly rigor.

He also developed an understanding of the racism embedded in the industry, which he found more subtle than overt—mostly. He has previously claimed that a chef de cuisine at Eleven Madison made racist remarks in front of diners and hampered his career as others were promoted.

People really kicked me when I was down, and I didn’t hurt anybody. I just started a business. I didn’t see why people were so angry.

“Racism is just as prevalent as sexism in the industry,” he tells Robb Report. “It’s something I face every day. There’s always that reminder of the color of your skin, no matter the situation. It’s still there. But I don’t let it get to me—it’s more of a motivation than anything else. I lean into my Blackness more than anything.”

After graduating in 2013, Onwuachi organized pop-up events across the U.S., which led to his Top Chef appearance. The next step, in Onwuachi’s opinion, was his own place, never mind that he hadn’t run a permanent kitchen before. But he had just enough chutzpah—and the faith of investors—to do it.

In November 2016, the Shaw Bijou arrived in Washington, D.C., with much hype. The spot was booked solid for months before opening. But the city wasn’t ready for a $185 15-course tasting menu from an untested chef. Onwuachi quickly slashed the price to $95, but Bijou shuttered after 10 weeks, an Icarus- esque fall. At 26, he was faced with the worst kind of flop: the public kind.

“There was a lot of vitriol online,” he says. “That was tough, seeing that publicly. People really kicked me when I was down, and I didn’t hurt anybody. I just started a business. I didn’t see why people were so angry.”

He was called out for his audacity to open Bijou with only the experience of a line cook, but he didn’t have to squint to detect racist undertones.

“I could definitely read between the lines of hate. It was loud and clear for me. But for sure, I just didn’t understand. It was like I had committed a crime, and I’m just cooking dinner,” says Onwuachi, who, seven years on, still speaks of the incident with a tone of incredulity.

On reflection, he insists he wouldn’t have done anything differently. “People ask: ‘Did you learn your lesson?’ But I just kept going,” he says. “I think that’s what true successful people look like. They just do it and don’t stop. They don’t get caught up in the noise. They do it because they speak whatever their craft is. I can’t explain why I’m so fascinated by this one thing, but it’s something I live and breathe.”

Onwuachi just wanted to cook, so in July 2017, he rebounded with a collaboration with Gorsha, a D.C. Ethiopian restaurant. Three months later, he was tapped to open Kith/Kin in the Intercontinental Hotel, at the Wharf waterfront complex in D.C. Praise rolled in, and two years later he nabbed that James Beard Award.

“It felt like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders—I was just at peace, I felt calm,” he says of the prize. “I went and ate a cheeseburger at Au Cheval after the ceremony. At the restaurant, I told my chefs it means nothing without us honoring it. It’s living up to it every day. We need to be doing it for ourselves. It’s ‘Thank you, I appreciate it, but we need to do the rest on our own.’ ”

In a New York Times profile in 2019, he proclaimed he wanted to open a “bajillion” restaurants. He laughs when asked whether the success of Tatiana has derailed or fueled that ambition.

“It feels like I said that 10 years ago,” he says. “I don’t know how many restaurants I want to open. I don’t think I want a lot, just something manageable. Not even that—I want something intentional. Tatiana for me is very intentional, in that I’m from New York and I’m coming back home. It’s my love letter to New York. Having a bunch of restaurants can dilute a message. I don’t think I’ll be having a bajillion. I’ll keep it tight.”

Best of Robb Report

Why a Heritage Turkey Is the Best Thanksgiving Bird—and How to Get One

The 10 Best Wines to Pair With Steak, From Cabernet to Malbec

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.