Chardonnay Has an Oak Problem

To clarify this intentionally provocative title, of course Chardonnay doesn’t actually have an oak problem. Chardonnay has an oak reputation problem. As a wine educator with regular guest-facing interactions, I’m frequently faced with Chardonnay prejudice, despite it somehow being among the best-selling grapes in America. In the wine service sector, the term “ABC” refers to those wine drinkers who are “anything but Chardonnay.” They’re otherwise not picky in their preferences for white wine. They just know that they don’t like Chardonnay. I meet these people every day. I try to convince them otherwise. Sometimes I am successful.

And why is it that Chardonnay is persona-non-grata in the minds of certain consumers? Is it because Chardonnay is such a complicated, off-putting grape? Acidic and thin? Aggressively floral? Funky and unpleasant? It’s none of those things, of course. Chardonnay expresses itself in myriad ways around the world, but as a grape it is fresh and lively, hinting mostly at nothing more offensive than green apple and lemon, with some tropical fruit development in warmer climates. What’s to hate?

The oak treatment often given to Chardonnay is what makes it so polarizing, in my experience. As the white grape most likely to receive it, even the slightest whiff of butter, and the ABCs run for the safe, diacetyl-free hills of Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc. I’d even argue that faced with the very term “Chardonnay,” many people cry “butter!” even when it’s barely there, or not at all, such is the power of suggestion in sensory evaluation.

It's important for wine consumers to understand that Chardonnay is often made unoaked, and that the buttery characteristic that comes from a particular kind of oak program does not define the grape. To write off Chardonnay because of a few oaky bottles would be the equivalent of summarily rejecting chicken because of a singular bad experience with barbecue sauce. Much of Chablis, an appellation in Burgundy whose grape is Chardonnay, is unoaked, and many Chardonnay producers the world over are committed to highlighting the purity of the grape with approaches to aging Chardonnay that minimize, or eliminate oak influence.

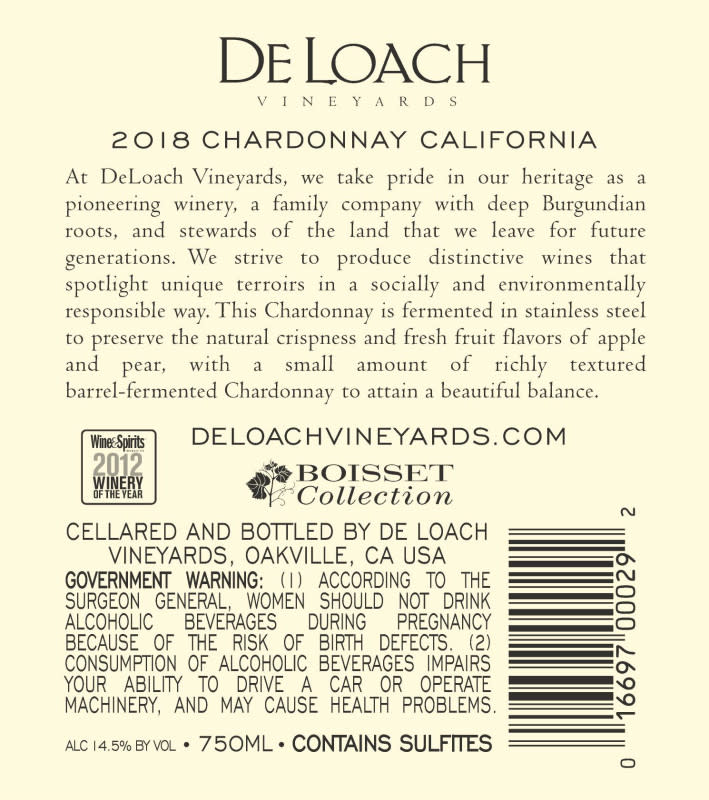

Even when Chardonnay is given the oak treatment, it’s never as simple as just “oaked.” Many winemakers assemble a complex cocktail of liquid in the final bottle involving portions of wine with various aging conditions, including oaked and unoaked components. When oak is used, there are myriad factors still: new, used, or neutral oak, as well as the varying sizes of the barrels, impart varying degrees of influence. American, French and Hungarian oak also result in different outcomes, as does how long the wine actually spends in oak, which might not be very long at all. Wine may be fermented in oak, rather than aged in oak, which exhibits different characteristics still. There is no “one oak fits all” when it comes to Chardonnay.

Malolactic fermentation also plays a role in the outcome of Chardonnay, leading to some richer textures, but when it comes to what consistently sets Chardonnay apart from other grapes as far as the haters go, it’s the assumption that all Chardonnay is big and buttery, which is simply not true.

Courtesy of DeLoach Vineyards

As much as I love to play the “gotcha” game with Chardonnay’s most determined detractors by pouring them something that isn't what they expect from the grape, the hard part is, it's really, painfully rare for the oak program for a given bottle to be made obvious in a manner that's easily accessible to consumers, or frankly, even professionals.

As a wine pro, tech sheets are often available to me that cover the minutiae of winemaking details for a given bottle. Arguably, this level of detail isn’t necessarily important to the average consumer. But something so definitional as the oak program, especially on a grape like Chardonnay that wears it so boldly, is crucial to a consumer’s understanding of whether or not they might enjoy what’s inside. Even as a professional, when I'm faced with choosing bottles from a retail setting, or from a distributor’s catalogue, there are few clues available that suggest how this wine is going to present itself outside the bottle. Sometimes I can make an educated guess with certain telltale tasting notes, but more often than not I’m forced to dig into producer websites for the kind of information I'm seeking. This is inefficient, and what's more, impractical, and certainly not something the average consumer standing in a bottle shop is going to bother to do.

Courtesy of www.drinkriesling.com

This, to me, is key information that belongs on the label, or would be an excellent use of a QR code. Riesling, another grape oft-maligned by the average wine consumer for its undeserved reputation for being exclusively sweet, recently got a leg up in this department, when the International Riesling Foundation created a simple scale that offers the consumer a metric for understanding the relative sweetness of a given bottle. Riesling may still have a reputation for being a “sweet” grape, but at least for someone in a position to help people understand otherwise, I've got handy information on the label I can point to.

Lots of other white grapes are occasionally subject to oak treatment, but none so consistently, and from so many regions, as Chardonnay. Oak is too complicated an approach to simply have a linear, “oakiness” scale, more’s the pity. Oak can't be measured quite in the same manner as grams of residual sugar. But until producers are committed to making this information more easily and consistently available, I’m afraid Chardonnay is never going to be able to drop the butter bomb stigma.