“These Are Challenging Times”: Rashid Johnson’s New Work Is a Powerful Response to Modern Anxieties

ART IS terrible as a quick responder to circumstance,” Rashid Johnson tells me when I visit him in late July at his country home on the East End of Long Island. The shingle-style house is set on five acres of wooded land, at a safe distance from the nonstop cocktail parties of the Hamptons. Johnson, still limping from a fractured cuboid bone in one foot, incurred while he played soccer three months ago with his young son, Julius, shows me into the all-in-one kitchen-living-dining room. The house is expansive and relatively new, and the furniture is as laid-back as Johnson, who made the 20-foot-long walnut dining table and the benches we’re sitting on.

“After the Trump election, people kept saying, ‘This is going to be a great time for art,’ ” Johnson says. “Honestly, it’s not. Artists’ practices take time—they’re not quickly conjured. But sometimes there can be nowness in it, and there are moments where I think my work does allow you, in an honest and emotional way, to see the now.”

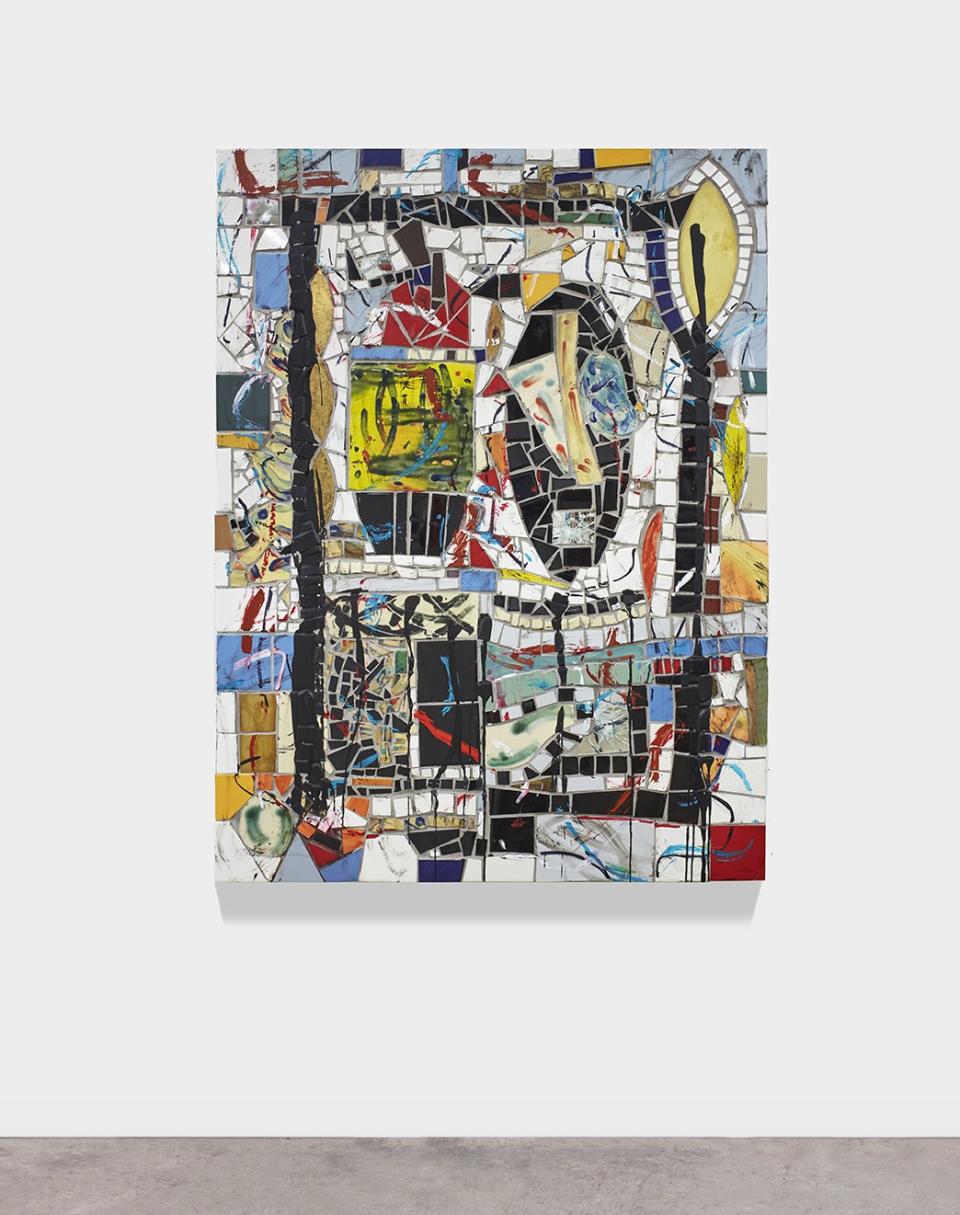

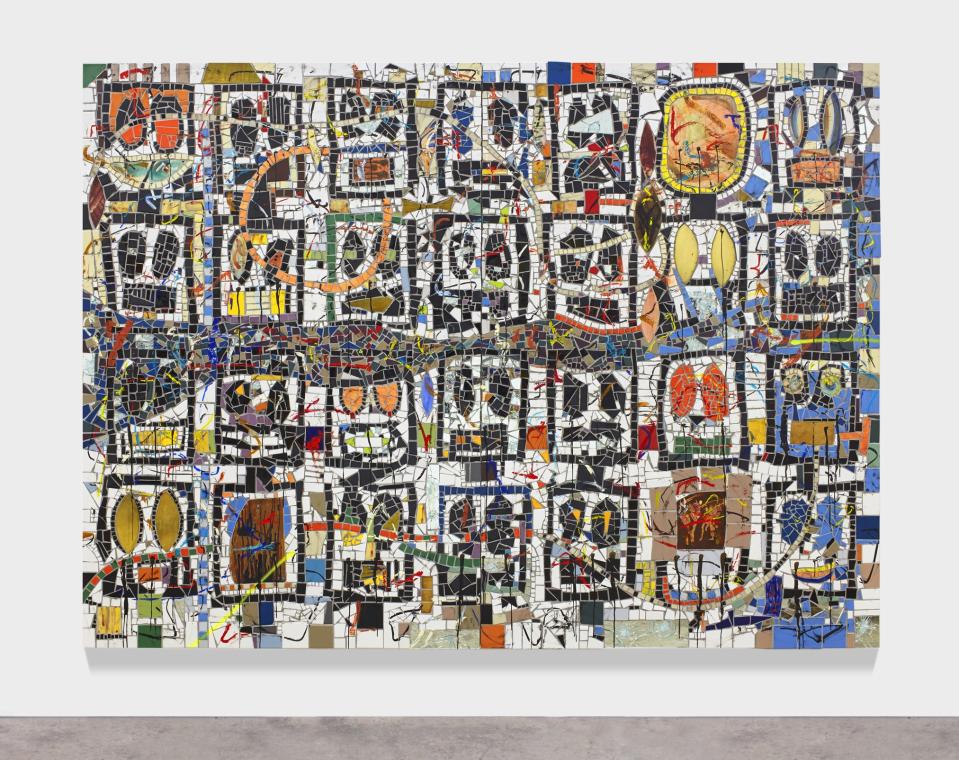

About five years ago, Johnson began a series called Anxious Men—boldly gestural paintings of black faces that he initially thought of as self-portraits. He had stopped drinking, and the ever-present anxieties of contemporary life had been intensified when he was “in social situations without the shield of alcohol.” But many people who encountered these portraits told him they saw themselves. “I realized I wasn’t alone in this anxious state,” he says. “These are challenging and troubling times.” By 2018, his Anxious Men (made from black soap and wax on tiles) had become Broken Men, large mosaic paintings made with fractured mirrors, scraps of wood, and shards from discarded ceramic sculptures. The anxiety on display feels heightened and permanent.

JOHNSON is a big presence, tall (six-foot-three), powerfully built, full of bursting energy and quicksilver intelligence. At 42, he’s one of the strongest voices in contemporary art, a multi-media artist who is immersed in the world around him, and this has been a breakthrough year. His first feature film, an adaptation of Richard Wright’s novel Native Son, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last January, and was picked up by HBO, where it aired in April. “I always knew I wanted to make movies,” he tells me, “and I’m likely to direct another feature film.”

In November, a solo exhibition opened at his New York gallery, Hauser & Wirth, where he has shown for the past eight years, featuring his latest art film, The Hikers. (The film was also the focus of two museum shows, in Mexico City and Aspen, this past year.) The seven-minute film depicts an encounter between two figures—one is ascending, his movements anguished and tortuous; the other is descending, moving proudly and triumphantly. Their wordless confrontation has elements of suspicion, anxiety, love, and recognition. “I tried to imagine the inner reactions of two black men, alone, hiking in a place like Aspen, where you don’t expect to confront someone who looks like you,” he explains.

Rashid was born in “arguably the first big era of unapologetic blackness,” says Naomi Beckwith, a senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, where Johnson was born and raised. (Beckwith, who sees herself as part of the same generation as Johnson, met him for the first time at an art opening for Kerry James Marshall.) “We always felt that our blackness was necessary, not an impediment. What does it mean to be a first generation that doesn’t feel the need to look respectable in a kind of bourgeois, Sunday-best way?”

Growing up in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Johnson was like the “bridge” between his two siblings—his brother was 10 years older, and his sister was 10 years younger. Their mother, Cheryl, a poet and scholar of African history who taught at Northwestern and later at Loyola, instilled in Johnson a profound respect for history and literature. “My mother is by far the biggest influence in my life,” he says. “Her intellectual curiosity, compassion, and empathy are the building blocks that make me up.” His father, Jimmy, is an artist who worked in publishing and then in electronics. Johnson’s parents divorced when he was two. A few years later, Cheryl remarried a Nigerian man, Carlton Odim, a lawyer whose pan-African interests added a new dimension to Johnson’s thinking. “I grew up with a lot of African imagery in our home,” he says. A poster for Ntozake Shange’s play for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf hung on a wall in his childhood bedroom. “I was interested early in every kind of art,” he remembers, “but I couldn’t really draw as a young person. I wanted to, but I was too impatient. I wanted to just conjure the thing. What I now realize is that I like to draw with my arm, not with my fingers.” As a teenager, he discovered graffiti. “The spray can and the big marker allowed me to draw in a more exaggerated and physical way and on a bigger canvas—and the canvas was the city of Chicago.”

In high school he was undisciplined, running with “kids who weren’t necessarily academic all-stars.” He almost dropped out but at the last minute “righted the ship,” he says. “Everyone in my family had a graduate degree.” He applied to Columbia College in Chicago with the idea of becoming a filmmaker. The summer before college, he spent every day in the library, reading bout the history of photography and post-1950s abstract painting and sculpture, and, as a result, arrived at school better informed than many of his freshman classmates. His student work impressed his teachers by mimicking the style of Robert Frank, Henri Cartier--Bresson, or Ansel Adams, and by the time he was 19, he was having exhibitions. “I was really cocky,” he admits. The Art Institute of Chicago bought a photograph out of his first solo show. Thelma Golden, then a young curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, saw that photograph and put it in “Freestyle,” her legendary 2001 exhibition of what she termed “post-black” art. The exhibition, which included Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford, and Eric Wesley, placed him on the art world’s rapidly changing map.

Though there was substantial interest in his work, he spent the next three years on his own in his studio, reading omnivorously and trying to figure out what sort of artist he could be. In 2004, he entered the Art Institute of Chicago as a graduate student; there he met his future wife, Sheree Hovsepian, an artist who works in photography and collage. He left before graduation to mount a show in Italy and didn’t go back. “I got the experience I was looking for,” he says. (The Institute recently gave him an honorary degree.)

When he and Hovsepian moved to New York in 2005, she tended bar at Good World on the Lower East Side, near their apartment, and Johnson subsidized the rent by letting the belly dancers working at the Greek restaurant upstairs change in his basement studio. “I’m not good at the logistics of life,” he says, “like meetings, day jobs, paying bills, or writing emails, the things people do to make them part of the group that we call human beings.”

It’s after two o’clock, time for lunch. Hovsepian comes in to pick up Bruno, their frantically barking Labradoodle, and take him outside, and we follow. There are four cars in the driveway and two in the garage, a Mercedes and a Tesla—he chooses the Tesla, and I follow him to Bobby Van’s in Bridgehampton. When we’re seated, I ask what “post-black art” means to him. “It’s something Thelma came up with,” he says. “I think she was talking about a generation of artists who grew up with a keen sense of their coloredness, but who were also trained in the Western tradition, invested in the ideas introduced by Duchamp as much as in the Negro spiritual. But it’s not something that I’ve ever identified myself with. When I’m asked about it, I often say that I am currently and presently black.”

Unlike many black artists of his generation and younger, he does not portray the black figure. But his own body is present in the materials he uses (black soap, shea butter) and what he does with them. The semiabstract, cartoonlike evocations of the figure by Jean Dubuffet, Philip Guston, and George Condo are major influences. “The thing those guys did that I feel real kinship to is employing the concept of the body or the face as a stand-in for emotions or ideas or ways of seeing and feeling. Talking to George the other day, I said, ‘You don’t paint people. You paint emotions.’ ” Condo echoes this idea: “Rashid’s work confronts and reflects the angst and the emotional crisis of our time,” he tells me. “Broken faces, broken people put back together again in his multicolored ceramic-tile paintings are cosmic entities of abstraction. He’s one of the few larger-than-life artists working today.”

IN LATE SEPTEMBER I visit Johnson in his supersize studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn. He’s wearing his summer uniform—black Rick Owens T-shirt and capri pants (in winter, the same black T-shirt with Saint Laurent black jeans). The studio is full of work for his show at Hauser & Wirth: large, colorful mosaic paintings along with oversize ceramic sculptures of the same blocky heads that appear in the mosaics, and a series of “Escape Collages” with cut-up images of palm trees, the ocean, African masks—symbols of the kind of exotic places his family couldn’t afford to take him on vacation when he was growing up. “I remember kids coming back wearing T-shirts with palm trees from Orlando and other places that felt so far away from me, so mystical.” Six assistants work in the studio, and two cats live here because Julius is allergic to cat fur. Johnson and his son have the same birthday, which they’ve just celebrated. (A long table is being set up in the studio for the eight-year-old and about 50 of his friends, who will go wild there tomorrow.) As we’re talking, a painting is delivered—it’s a portrait of Johnson by his friend Henry Taylor, the much-admired Los Angeles artist. The scene is chaotic; Johnson is relaxed, perfectly at home in his skin.

There will be one really big sculpture in the show, a huge bronze head with a palm tree growing out of the top and cacti, grasses, and ferns growing out of the eyes and sides. “I’ve always thought about connecting plants from different places and putting them together in unexpected ways,” he says. “It was explained to me once that creativity is best thought of as a person who is willing to connect disconnected things. Artists are not looking for the logical solution, or the most tasteful or pragmatic solution. We’re often looking for the disparate solution, the disconnected, desperate, unhealthy, unthoughtful solution that we can bring into the world, and maybe it changes how we think. That’s kind of the goal. The first guy who put peanut butter and jelly together probably wasn’t celebrated, but now we all believe it to be true.”

Johnson’s work has always been closely aligned with music, and even when it is not an explicit part of an exhibition, the work has musical inspiration. For the current show, it’s the album Volunteered Slavery from the late jazz musician Rahsaan Roland Kirk, particularly a song called “Search for the Reason Why.” He plays a snippet for me on his iPhone. “He’s asking you to search for why,” Johnson says. “And that’s it—that’s why I come here every day. Not that my thinking is more important or more interesting than the way anyone else thinks, but I feel like I’m the only me—and I’m really excited to share.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue