Cereal, conspiracy theories and 9/11: the curious legacy of Supertramp’s Breakfast In America

Progressive rock is a critically much-maligned musical genre, flourishing in the Seventies in the wake of psychedelia and drawing in elements of classical, jazz, world and experimental music liberally doused with fantastical lyrical concepts. This is sometimes ungenerously dismissed as a period when rock started to take itself too seriously and almost disappeared up its own 30-minute solos, before its grandiose excesses were curtailed by the arrival of punk and new wave.

Yet the best of “prog” (including masterpieces by Pink Floyd, Genesis, King Crimson, Yes, Rush, Soft Machine, Jethro Tull, Can and even the unrepentantly excessive Emerson, Lake & Palmer) was boldly idiosyncratic music that stretched boundaries in imaginative ways. It was certainly a great field for album cover design. Progressive rock bands wanted a sleeve that reflected their seriousness of intent and enhanced thematic concepts, resulting in some of the most elaborate and innovative artwork in album history. There was a lot of visual wit on display, never more so than on the album that made minor British prog rockers Supertramp a transatlantic phenomenon.

What is it?

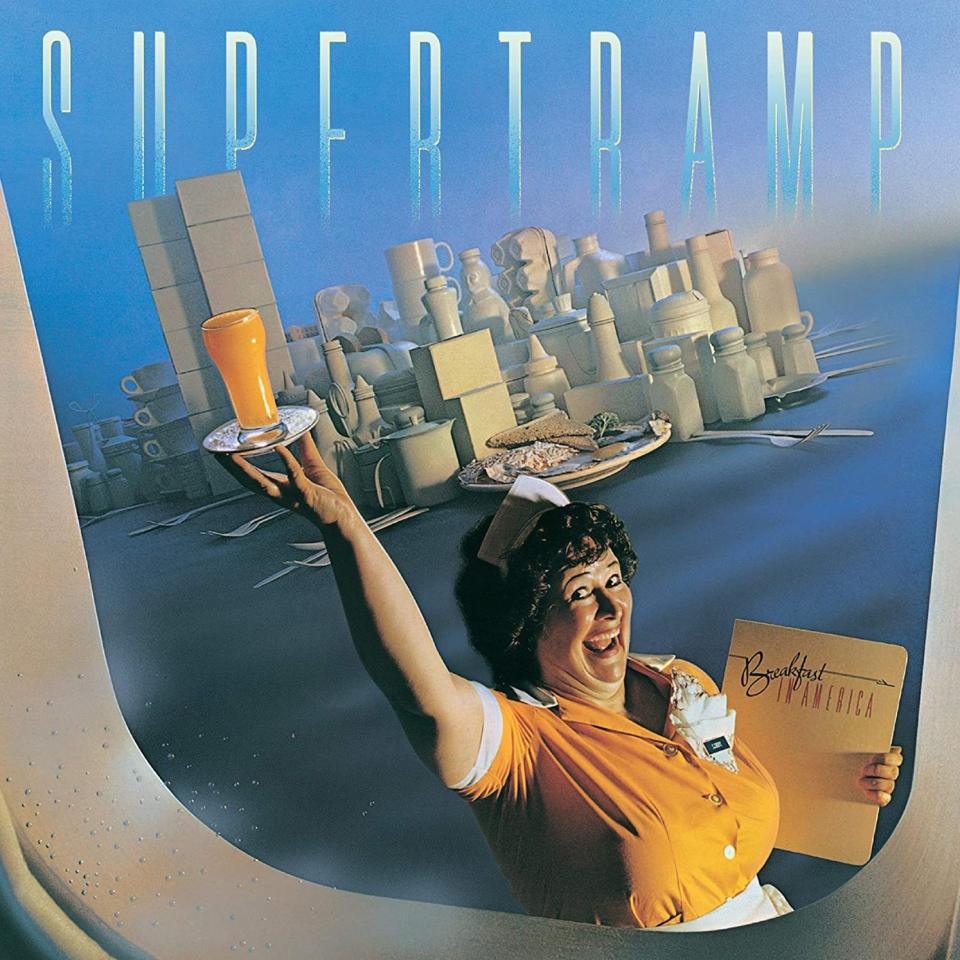

Breakfast in America was Supertramp’s sixth album, released in March 1979. The cheerful photographic cover appears to show a view from an airplane descending on New York, in which downtown Manhattan has been constructed from stacked coffee mugs, egg cartons, salt shakers and condiment bottles rising above harbours of cutlery. The Statue of Liberty has been replaced by a matronly, smiling waitress in a uniform, carrying a menu displaying the album title and holding a glass of orange juice in place of her flaming torch. “The cover expressed with wry humour our mental and physical place at that time,” according to sax player John Helliwell. “Living in the land of dreams and ambitions, and substituting the English transport café for the friendly diner.” The back sleeve photograph extended the theme, depicting the band actually in an American diner being served by the same waitress, while all reading local English or Scottish newspapers from their home towns.

How did it come about?

Supertramp formed in 1969, developing a songwriting axis around multi-instrumentalists Rick Davies (the one with the rockier, baritone voice and jazzier piano style) and Roger Hodgson (with the high voice and Wurlitzer electric piano). It took them several albums to really find an audience, with tensions developing between Davies’s more experimental ambitions and Hodgson’s poppier instincts. Although Crime of the Century (1974) is considered a prog classic, it was its hit single Dreamer that was to shape the band’s future direction as purveyors of a concise and sophisticated prog pop, akin to UK contemporaries 10CC and ELO, and Steely Dan in the US. Supertramp never appeared on the front of their albums. “We wanted to be around a long time, and we didn’t want people watching us getting older,” according to Davies. “We were a pretty imageless lot, anyway.”

The band relocated to America in 1978, basing themselves in Los Angeles for eight months of dedicated writing and recording. Serious divisions were starting to emerge between the down-to-earth, working-class Davies and the privately educated and increasingly esoteric Hodgson. The working title for the album was Hello Stranger, and it was intended as a conversation representing the opposing views of the songwriters, the bones of which remain visible in such songs as Goodbye Stranger, Casual Conversations and Child of Vision. The band quickly recognised that they were working on something potentially strong. “We definitely didn’t want to go overboard, because we were conscious of some groups going on and on with long, long solos and complicated arrangements,” said Helliwell. “We wanted everything to be tuneful and succinct.”

Another strand of songs was emerging, reflecting their experiences in the US, including Gone Hollywood (by Davies) and Breakfast in America, which Hodgson had actually written many years before he visited the US. The song reflects a naïve and parochial British perspective of America, in which the singer imagines having kippers for breakfast in Texas where “everyone’s a millionaire”. According to Hodgson, it was co-opted for the album title simply because they wanted something light-hearted.

“It was a fun title. It suited the fun feeling.” To create the sleeve, they turned to art director Mick Doud, whose work had included Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti. Doud produced various sketches on the theme, including giant Cheerios rolling down Arizona’s Monument Valley in a flood of milk. The band opted for his Statue of Liberty concept, which artist Mick Haggerty was hired to execute. It was Haggerty who persuaded the band to stage it for real. The cover is a composite of four different photographs, with added airbrushing. Haggerty built the model Manhattan, spray-painting everything white.

His attention to detail is impressive. The World Trade Center was constructed from cereal packets, and Battery Park and Staten Island Ferry Terminal were made from a plate with a breakfast of scrambled eggs and toast. The Statue of Liberty waitress even has a name tag identifying her as Libby. They found their cover star, Kate Murtagh, via the Ugly Model Agency. She was an actress and singer-comedian who had roles in many films and TV series, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Munsters and The Twilight Zone. She proved so popular that Supertramp took her on tour, where she would introduce the band every night.

What does it sound like?

Breakfast In America proved a perfect synthesis for the talents of Supertramp’s very different songwriters. It features 10 philosophical and melodically fluid songs burnished to a high degree, played with panache and concision by the virtuoso five-piece band, with Davies and Hodgson presenting a sense of harmonic unity as their distinctive voices merge. Hodgson’s The Logical Song became Supertramp’s biggest hit single, a pop classic confronting the way education represses childhood imagination. If there is a tension between Hodgson’s dreamy songs of spiritual idealism and Davies’s more gritty take on life (Oh Darling, Just Another Nervous Wreck) it vanishes in the smooth cohesion of the production.

The album topped charts around the world (including six weeks in the US), spawned four hit singles and went on to sell close to 20 million copies at the height of new wave and disco, when prog rock was supposed to be past its sell-by date. Clocking in at just 46 minutes playing time with only the climactic final coda of Child of Vision really breaking out for the stratosphere, it is hardly typical of the genre. Yet its sophistication and enduring popularity do demonstrate that the adventurous values that fuelled progressive rock may be more resonant and durable than the genre’s reputation suggests.

What is its legacy?

Breakfast in America won a Grammy for Best Album Package in 1980. Artist Mick Haggerty went on to a long and successful design career, creating sleeves for David Bowie, The Police and Roxy Music, among many others. But the seeds of Supertramp’s dissolution are there. Hodgson quit in 1982 to pursue a solo career after one more fractured album, Famous Last Words. Davies continued as sole songwriter until 1988, periodically reforming different line-ups for albums and tours.

The strangest aftermath of this elaborate cover emerged in a widely reported news story from 2016 about a conspiracy theory circulated via a David Icke forum. It was claimed that Supertramp were funded by sinister masonic forces and that Breakfast In America predicted the September 11, 2001 attacks on New York. If you hold the cover up to a mirror, the letters U and P floating above the cardboard box Twin Towers reads 9 11 apparently. “Damning evidence, for sure,” as Haggerty wryly remarked. “Although I made this image 20 years beforehand.” It may be a very silly story but it is a reminder of the imaginative power a great album sleeve can exert.

What are your memories of Breakfast in America? Neil McCormick will be in the comments section below between 4pm and 5pm on June 18