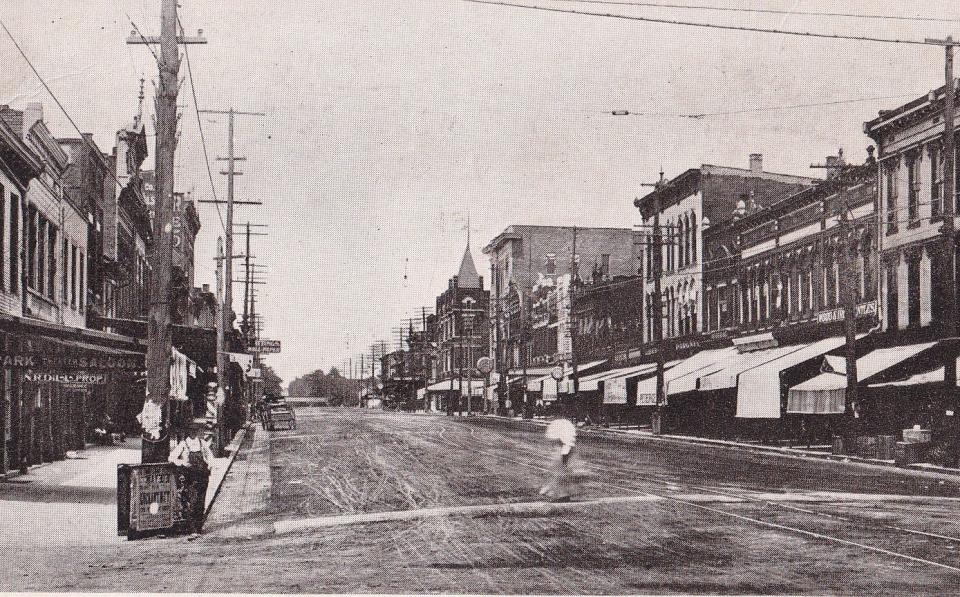

A century ago, Henderson rolled into the automotive age

Henderson had seen its first cars two decades earlier, but it wasn’t until 1923 that the Henderson City Commission motored into the automobile age by adopting new traffic regulations and starting its first major street paving program.

The Gleaner of July 6, 1923, reported the commission had passed five ordinances authorizing the paving of 33 blocks. (That was just the beginning, however; by 1928 the city had 12 miles of paved streets.) A contract was awarded to the Andrews Asphalt Construction Co. of Hamilton, Ohio, according to the July 25 Gleaner. More about the paving, which began Aug. 16, in a moment.

The city commission passed an ordinance Sept. 10 regulating the flow of traffic “by pedestrians and persons using vehicles.” Many of the provisions now seem a bit obvious, such as don’t drive while drunk, don’t double park, and yield right of way to police cars, fire engines and ambulances. Drivers under 16 were prohibited unless accompanied by the vehicle owner or someone over 21.

The city commission also thought it necessary to tell motorists to not park abreast of the traffic flow.

But some of the rules were not so obvious. For instance, you also had to yield to postal vehicles and streetcars.

New speed limits were also instituted: 10 mph within 300 feet of a school, 15 mph in the business district and 20 mph in residential areas. The business district was bounded by Water, Fourth, Ingram and Washington streets.

Special angled parking was required in the business district – but it got a bit confusing on Second Street between Water and Ingram streets. Angled parking was also required in that area, but “vehicles shall be parked in the center of the street, with the right hind-wheel against the curb of the 18-foot driveways.”

The new traffic ordinance went into effect Sept. 11 and that morning found Officer Rupert Sutton standing at the corner of Second and Main streets directing traffic. “I’m just tellin’ ‘em; I haven’t gone to catching ‘em yet,” the khaki-clad policeman said in the Sept. 12 Gleaner.

Sutton apparently was conscientious. Police Chief Ben McKinney absent-mindedly jaywalked and Sutton “told it to him.”

Frank Haag, commissioner of public safety, had instructed Sutton to not begin citing violators unless it appeared they were flagrantly flouting the new traffic ordinance.

Sutton said most drivers appeared to be adapting well to the new regulations, according to the Sept. 13 Gleaner.

“The greatest trouble I’m having is the jaywalkers,” he said, noting he had just sent four men back to cross at the corner. Haag was quoted in the same story noting crosswalks would soon be painted on the newly paved streets.

Sutton was going to be “saved a lot of gesticulating,” according to The Gleaner of Oct. 3. The public safety commissioner had ordered a semaphore traffic signal from the Union Iron Products Co. of Chicago, which had two large oval plates, a green one with GO on it and a red one with STOP. It was to be installed at Second and Main streets.

“This sign has a 60-pound iron base, is of heavy metal tubing and is eight feet in height. It is surmounted by a regular semaphore lantern with red and green lenses,” which could use either oil or electricity for lighting. “The sign is operated easily at the will of the traffic policeman.”

Local life: Soft serve truck with endless options hits Henderson

Now, let’s shed a little more light on the city’s first major paving project.

The Gleaner of Sept. 12 reported Second Street had been apportioned and property owners there would have to pay their share costs of the paving. The total amount was $59,154, although the city was picking up $7,555 for the costs of paving intersections.

Two steam shovels were getting ready to excavate the base of Green Street, which required using Sand Lane as a detour, according to the Sept. 16 Gleaner. At that point it was called South Street or Sand Hill Road because of the sand, which was so deep mule teams sometimes had to pull out bogged down cars. Rock had to be applied to solve that problem.

The Gleaner of Sept. 25 reported excavation had begun on Washington Street; two concrete mixers had begun work at Green and First streets and completed a full block the day before. (The paving was composed of a concrete base followed by two layers of asphalt.)

The asphalt plant was set up at the foot of Fifth Street and spreading it began in early October. The job was expected to be completed by the end of the year.

The Gleaner of Oct. 3 noted the newly paved portion of Main Street – from Second to Fourth -- was inaugurated with a dance and a speech by Mayor Clay Hall: “Nearly two years ago your mayor and commissioners went in on a platform of better streets, and we are now seeing the completion of some of these streets…. By this time next year, you will see (the remainder of) Main Street paved just like this from Sand Hill to 12th Street.”

The Gleaner of Oct. 31 noted Green Street had been paved between Hancock and Sand Lane, and that work was proceeding on Washington and Second streets.

All concrete work had been completed, according to the Nov. 6 Gleaner.

The entire paving program of 1923 was completed at 5 p.m. Dec. 3, according to the following day’s Gleaner. The result was Green Street paved from Sand Lane to 12th Street and Second Street paved from the railroad tracks to Water Street. Main and Elm streets each saw a few blocks paved.

Only about a mile of city street had been paved prior to 1923; the 33 blocks done that year brought the total to more than five miles. The work cost approximately $230,000.

75 YEARS AGO

A Lima, Ohio, man and wife were injured in a crash at the Henderson Airpark north of Henderson, according to The Gleaner of Sept. 5, 1948.

Manuel Rice, 23, and his unnamed wife, 25, were recovering from injuries at Henderson Hospital. Rice suffered “severe cuts to his face” while his wife suffered an injury to her pelvis.

Rice told newsmen he had just taken off when the aileron control locked. “I guess I just lost my head,” he said. The plane, which had gained an altitude of about 50 feet, nosed into a cornfield.

The couple had stopped in Henderson overnight while on their way to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, to visit relatives.

50 YEARS AGO

The Kingdon Hotel on Second Street was a pile of rubble by Sept. 9, 1973, but several people reminisced about its glory days to Anna May Nesmith of The Gleaner.

The large building was erected in 1890-91 by Louis P. and Charles F. Kleiderer. They fell on hard times and sold the hotel to Charles F. King of Corydon, and the hotel was renamed in his honor.

Nesmith interviewed Melicent Quinn, who came to Henderson as a bride in 1913, and Willie Reeder, who was a bellhop at the hotel for 35 years.

“The mammoth dining room was rather dark,” Quinn recalled. “There were no windows and I remember in the summer it was always cool. The linens were all white and so crisp I wondered how they kept them that way….

“Another thing I remember was the long row of sturdy wooden armchairs that lined the sidewalk outside the hotel under the canopy. That’s where the ‘traveling men’ and other guests sat except in the bitterest weather. It was a bit of a trial to walk down that side of the street because you would feel you were being inspected from head to foot!”

Reeder remembered different modes of transportation. “There weren’t as many cars or good roads then, and people came into Henderson by train or bus. The hotel was always full of guests; many of them were show people who came here to perform.

“I remember when Tex Ritter was here and Jack Stalcup (of Paducah) and his orchestra stayed almost every weekend and played at the old Kasey Klub.”

25 YEARS AGO

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had tentatively concluded placing about 9,750 tons of rock on the east side of Horseshoe Bend was a good idea, but was seeking public comment on the proposed project, according to The Gleaner of Sept. 3, 1998.

Years of flooding had cut a 350-foot-wide breach in the existing revetment, which had been built in 1933-34 and expanded in 1940. Fears had been expressed since the 1880s that the river would cut across Horseshoe Bend and leave Evansville high and dry.

The Corps of Engineers spent about $1.3 million in 2003 to place about 314,000 cubic yards of stone and broken concrete to fill two large scour holes the river had carved, one of 7.3 acres and the other of 3.2 acres.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com, on the social media site formerly known as Twitter at @BoyettFrank, or on Threads at @frankalanks.

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: A century ago, Henderson rolled into the automotive age