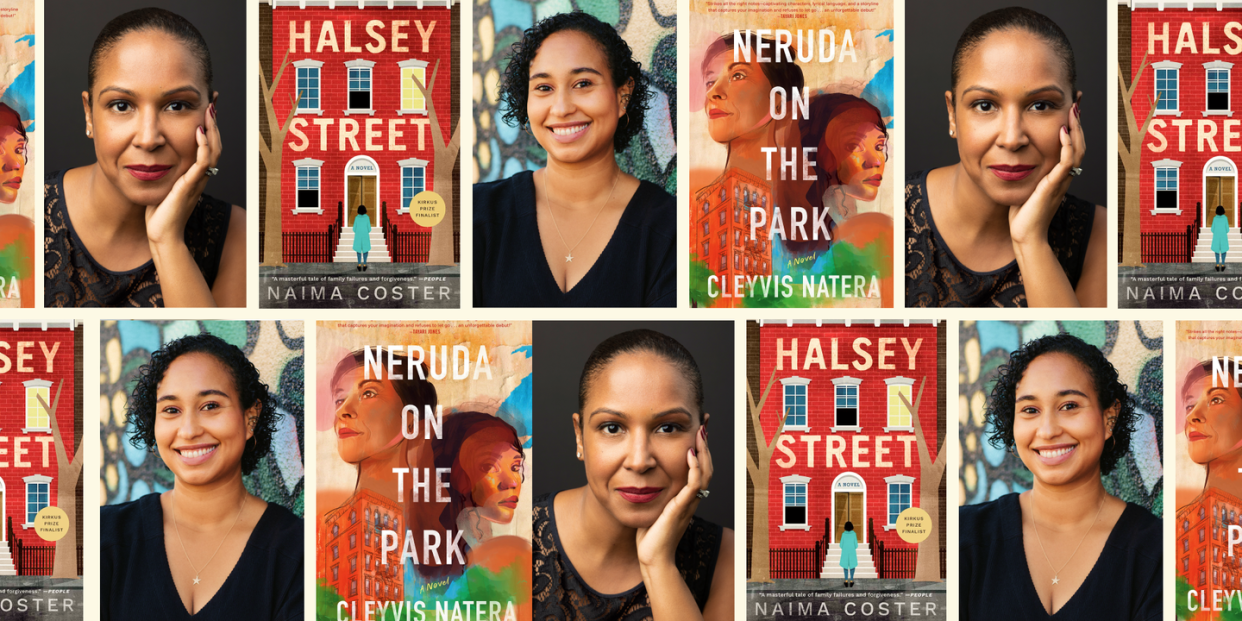

Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month with Cleyvis Natera and Naima Coster’s Exploration of Afro-Dominican New York

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Like their upbeat, New York–bred authors, the novels Neruda on the Park and Halsey Street converse like sisterly companions. Neruda on the Park, published in May, features Luz Guerrero, an Ivy League–trained corporate lawyer close to her Dominican community in upper Manhattan but untroubled by the encroaching gentrification. Halsey Street (2017) centers on Penelope Grand, adrift after dropping an art career and ambivalent about her Brooklyn neighborhood, Bedford-Stuyvesant, where gentrification has forced her African American father to close his popular record store. Both are approaching 30, battle troubled Dominican mothers, and embark upon risky romantic entanglements with affluent white men. In a Zoom meeting, the authors and I chatted with familial ease about Washington Heights and Bed-Stuy, the neighborhoods where they grew up.

Their novels triumph by admiring their characters and settings while still spotlighting their blemishes. Nearly everyone seems askew at some point, and every street corner can be potentially uninviting as well as vibrant. The novels veer into surprisingly dark territory, and they don’t aim to uplift us the way the film musical In the Heights highlights the New York Caribbean Latinx community at street level. Natera and Coster instead offer the reader a more tempered celebration. “How can you honor a place or a people without pretending that there are no problems or undersides?” Coster asked. “Just like the families are worthy of love and honor, even if they're messy, I don't think that we need nostalgia or some kind of false virtue to say people shouldn't be displaced.”

Luz is the more rooted in her community, Northar Park, but grapples with the label of outsider, marked by her lost Spanish. “It’s a love story of a girl and her neighborhood,” Natera explained. “But there's hostility against Luz and who she is and how she presents. At the same time, people are very proud of her.” Tensions flare as longtime residents react differently to the construction of a condo complex and news that developers are trying to buy out renters in the Guerreros’ nearby apartment building. Eusebia, Luz’s mother, launches a drastic sabotage campaign to drive out developers, which ends up pitting neighbor against neighbor.

Penelope’s relationship to Bed-Stuy is perhaps more fraught because since childhood she’s always had difficulty feeling she belongs. As a child, she’d walk along Halsey Street, more likely to hear men’s catcalls than see girls skipping rope. Gentrification creates a sense of safety for her despite undermining the rich Black cultural vibe her father Ralph’s record store represents.

The novels are particularly textured in their treatment of race, and when paired, they offer a rich diversity of Black identities. Luz and Penelope are both Afro-Dominican, but their racial and cultural experiences differ. We are conscious from the opening paragraphs that Luz is dark-skinned—the color of a brownstone—and her friends and relatives often compliment her on her beauty. Her mother affectionately describes her as “cafecito,” but also refuses to say Black, a hesitance Natera explained, that indicates colorism among Dominicans. “There is no other way around it. There is an anti-Blackness within our own community,” she said. Light skin is often equated with beauty, dramatically when Luz’s aunt Cuca travels to the Dominican Republic for full-body plastic surgery that includes skin bleaching, a popular procedure in the country. The issue of colorism and the Afro-Caribbean community exploded into a public controversy last year when the film musical In the Heights was released. The film’s producers came under criticism for casting light-skinned actors in most of the central Latinx roles, while dark-skinned performers appeared mainly as extras and dancers.

When Eusebia avoids saying Black, though, she also expresses a maternal wish to protect Luz against the impact of racism. “Luz’s dark skin makes her mom concerned about the harshness of the world,” Natera said. “So often we are anxious about our children because of the color of their skin.” According to Natera, this fear may be a reason for the resistance that Afro-Caribbeans can have to connecting with African Americans. “I thought a lot as I was growing up about the divisions that existed, especially in Harlem and in Washington Heights, between Black Americans and Dominicans. A lot of Dominican immigrants would align themselves as not being Black. It was explicit in the text that Northar Park was a neighborhood that Black Americans were in before it became an immigrant neighborhood.”

But Natera also foregrounds bonds between Afro-Latino and African American women. Luz’s lawyer colleagues are African American women who try to steer her through the brutal, adversarial world of corporate law. “Luz is invited into this women’s group explicitly because she presents as a Black woman. It’s important for us to think about solidarity,” Natera said.

Coster’s Bed-Stuy, in contrast, is historically an African American neighborhood, with minimal Latinx presence. Penelope speaks fluent Spanish but must travel to the Dominican Republic to express her Dominican self. While she is bicultural, her parents are culturally alienated from each other. Her mother, Mirella, never feels she belongs in Bed-Stuy among Ralph’s African American friends, and she eventually moves back to the island. Throughout the marriage, Ralph focuses on his store and shows little interest in Dominican culture. The separateness is complicated by color. Mirella could be classified as Black, but she’s light-skinned and red-haired. “I was trying to portray multiple relationships to Blackness,” Coster said, “not just in terms of color, but in terms of internal feeling and recognition. Mirella moves through the world as someone who's ethnically ambiguous and white presenting. Despite her heritage, it shapes the way Mirella feels about the gentrification. She can slip into the coffee shop and the gentrified world in a way that Ralph cannot because of color.”

Both authors often write against conventional racial storylines. They sometimes foreground racial identity and at other times leave race implicit or vague, which accents the ambiguities that challenge how we read race in American life. Natera makes a powerful statement by casting Luz’s lawyer colleagues as Black women. Coster, on the other hand, drops barely a racial identity clue about Penelope’s boyfriend in the book’s second half. When Coster asked me to describe my sense of his racial identity, I suggested “Black rocker.” She laughed, while staying mum.

Luz and Penelope have another parallel struggle, which is built into the books’ narrative structures—trying to connect with their mothers. Eusebia and Mirella alternate as narrators with their daughters, an approach that in both cases teases out the differences between mother and daughter, while also conveying an implicit dialogue. And through the relationships with their Dominican mothers, Luz and Penelope are also in dialogue with the Dominican Republic itself, a homeland that is core to their identities but remote for much of the stories, in contrast to Bed-Stuy and Northar Park, where we hear the daily noise of construction cranes and shouting children. In Neruda on the Park, Eusebia, though she still barely speaks English 20 years after immigrating to the U.S., no longer identifies with the Dominican Republic. For her, the island embodies the traumatic losses she suffered there. Natera said she wanted the story to be “an anti-narrative” that resists nostalgia. “I wanted characters to not long for home, immigrants who consider New York City their home.”

Halsey Street reverses the relational equation in a way because Mirella finds refuge in the Dominican Republic after years of isolation in New York. For Penelope, the island was once an intimate place where during summer trips she painted watercolors and communed with her affectionate grandmother. But the country symbolizes separation because when Mirella moves back, Penelope feels abandoned. In the book’s last section, they encounter each other, but Coster does not spell out how much reconciliation may have occurred. “I decided to make the mother the repentant one who longs for her daughter once her daughter is grown, the way her daughter longed for her when she was a girl. And they both resist the other one’s desire for connection. One of the questions I’m asking is whether it’s love if it’s never really enacted or realized or received.”

“Naima and I have talked about where reparation is,” Natera reflected. “Where are we as a country? How can we ever get to a place of repair if we can’t be honest with ourselves about the harm we cost, even if it’s in the pursuit of love, even if it’s in the pursuit of freedom?”

You Might Also Like