What is Catalan Modernisme? How Modernism Became Barcelona's Predominant Style

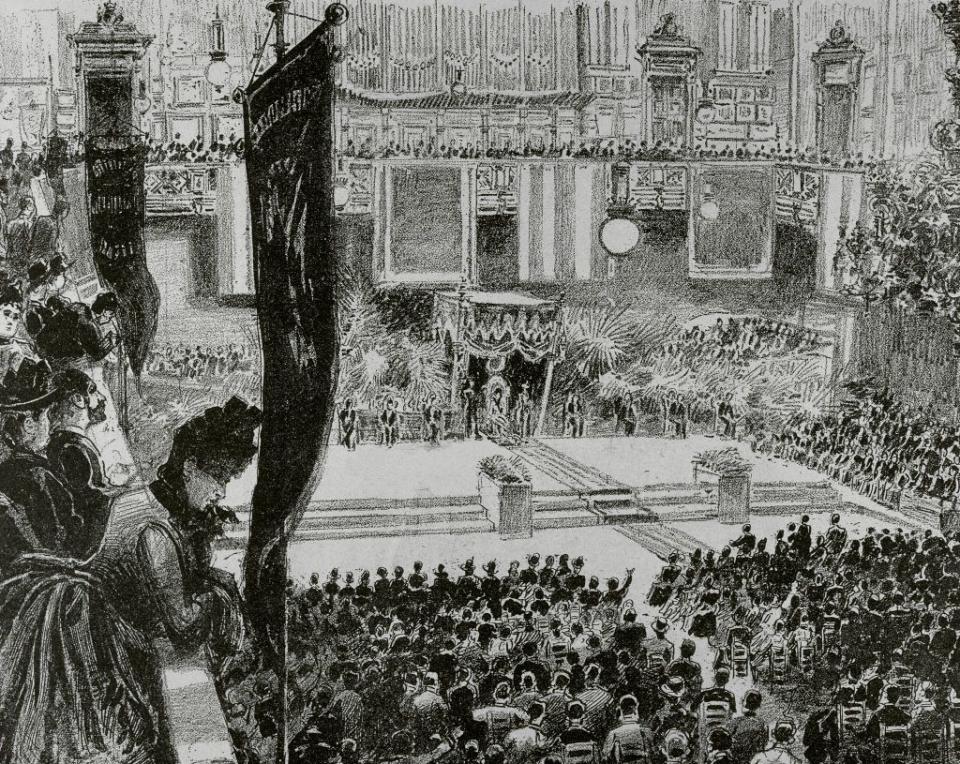

Excitement erupted from the streets as people from across Catalonia arrived in Barcelona to discover the thrilling industrial and cultural wonders being exhibited at the 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition. The stodgy citadel locals had grown to detest was replaced with a grand green space akin to New York’s Central Park, and to visitors’ shock, an extraordinary castle-like structure stood in the background with large blue-and-white shields and fantastical motifs. Architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner intended for Castell dels Tres Dragons to be a striking café that would wow guests at the fair, but it instead became the starting point for modernisme in Barcelona.

Catalan modernisme refers to not just an artistic style, but a cultural movement that spanned across architecture, art, music, literature, and society as a whole. “Modernisme has many faces and echoes a certain ambiguity,” says Mariàngels Fondevila, curator at Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. “But if there is a characteristic feature, it is the vocation for modernity and international openness in a context of transformations and crises.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Catalonians began flooding to Barcelona in hopes of finding work at newly opened factories. Local authorities quickly began expanding the city to compensate for the growing population with a new district known as Eixample. Fondevila says that Eixample, in combination with the Barcelona Universal Exposition, helped establish modernisme as the “aesthetic code of the new urban culture.”

This up-and-coming neighborhood soon became the stomping ground for architects yearning to have a hand in this new vision for Catalan society. At its core, modernisme favors asymmetrical shapes and curved lines often seen in the natural world, but the architectural movement still calls upon its historic predecessors.

Montaner’s Castell dels Tres Dragons is often considered the earliest example of modernist architecture, yet its crown-like battlements directly reference Gothic style. His later masterpiece, Palau de la Música Catalana, combines more traditional Gothic and Moorish architectural elements with showstopping displays of glass artwork and sculpture. Mireia Freixa Serra, professor of art history at University of Barcelona, explains that this balance between old and new was fundamental to the new architectural current. “The Catalan movement presents a clear paradox: It retains its roots yet at the same time defends the most radical modernity,” says Serra.

Montaner, of course, wasn’t the sole architect experimenting with new materials and shapes during this time. Antoni Gaudí has long been considered one of the top exponents of modernisme, using his knowledge of international styles—Asian, Islamic, and even Art Nouveau—to create his own eclectic approach.

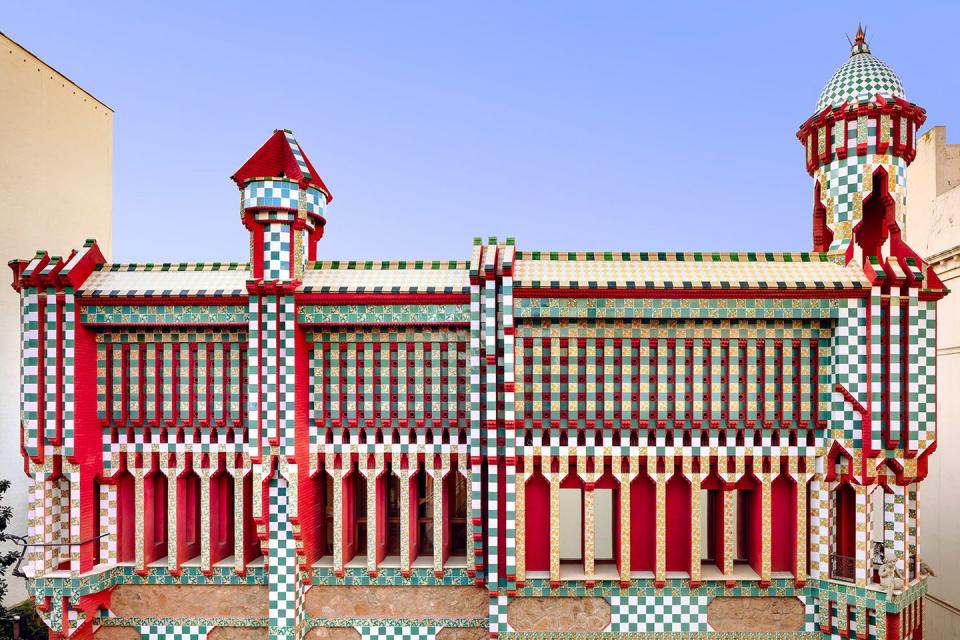

The mastermind behind many of the eccentric buildings defining Barcelona’s cityscape, Gaudí’s first prominent project came when Manel Vicens approached him to design a summer home in 1883. For the young architect, a family home was not just a dwelling for people to stay in—it was the epicenter for one’s life. In La casa pairal, one of the few surviving documents from Gaudí, he wrote:

“A house is the family’s miniature nation. The family, as a nation, has a history, exterior relations, changes of government, etc. An independent family has its own house; the family that is not, rents a house. An owned house is the country of birth; a rented house is the country of emigration. This is why owning a house is everyone’s dream.”

His vision for Casa Vicens was to build a home that could be understood as a whole and where each decorative element directly played off one another. According to Pilar Delgado, the chief digital officer of Casa Vicens, the floral motifs seen on the tiles decorating the home’s facade were inspired by the marigold flowers littered throughout the property. Serra adds Gaudí use of ceramics and tiles in Casa Vicens became a hallmark of his style as it “made it possible to bring color to architecture and see it as a living element.”

As his career progressed, Gaudí's refined his distinctive style more by turning to nature to influence the colors and forms he often used in projects. It is believed that the iconic Casa Batlló is the architect's interpretation of marine life. Made of recycled materials and odd objects, the facade of the structure looks as though it's reflecting the anatomy of a creature. Slender stone columns resembling bones lead up to an explosion of florals one could argue references blood vessels. The structure is crowned with a Technicolor tiled roof echoing the scales of a fish or dragon.

This broad use of vibrant colors and intricate tiling continues into the interiors, most predominately in the bright blue patio of lights. A fundamental part of the house, the patio of lights, was used to distribute air and natural light to each room in the home from a skylight above. Gaudí also made a point to collaborate with the most skilled artisans of the time to create the stained glass, ceramic tiles, and stone ornament throughout the home.

While visitors flock to see the exuberant Casa Batlló, Gaudí most famous and astonishing work happens to be the one he never finished. Gaudí served as the lead designer and architect for the Basílica de la Sagrada Família starting in 1883. A devoted Christian, religious imagery and symbolism appeared in many of his works, earning him the nickname "God's Architect." The Sagrada Família was a way for Gaudí to express his deep religious faith and his divine vision for Catalan architecture.

Gaudí's plan for the basilica consisted of 18 spires to represent lead figures from the Bible: the largest tower dedicated to Jesus Christ, 4 towers for the Evangelists, a tower for the Virgin Mary, and 12 towers for the apostles. Gaudí acknowledged he would never fully see his extravagant vision come to life and even left detailed plans and models for future architects. Tragically, his time on the project was cut even shorter as he was killed in a tram accident in 1926.

More than 100 years later, the Sagrada Familia is still under construction with generations of architects embodying the spirit of modernisme in their own ways—just as Gaudí would have wanted. The legacy of this cultural movement can be seen not only in this project but the countless buildings lining the streets of Barcelona. And while architects like Montaner and Gaudí may have had a direct hand in building Barcelona into the artistic capital it is today, it was their and their cohorts' forward way of thinking that further shaped the Catalan spirit.

You Might Also Like