The Case for Age Limits in American Politics

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

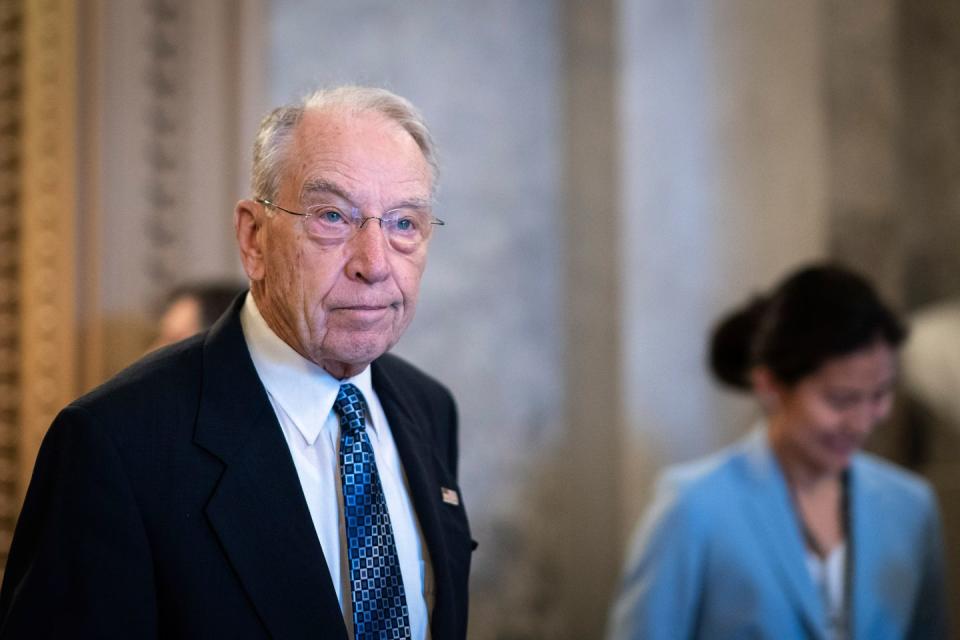

When Senator Chuck Grassley first got into politics, Ike Eisenhower was president of the United States. It was 1959, the same year the first transcontinental commercial flight made it from Los Angeles to New York’s Idlewild Airport, later to be renamed in honor of John F. Kennedy. Late in the year, IBM introduced the 7090, a milestone computer model that relied on “transistors, not vacuum tubes.”

Grassley served in the Iowa House, then served three terms in the U. S. House. He’s now in his seventh term in the Senate. And he announced last September, a week after his 88th birthday, that he’s running again. That will make him 95 years old at the end of his next term. Simply put, this is too damn old to be doing this job. It’s too old to be doing just about any job.

The FAA mandates that pilots retire at 65. Their colleagues in air-traffic control are out at 56, though they can get exceptions to work until they’re 61. Most police departments show employees the door in their 60s. At white-shoe law firms, partners are often pointed to the exit sign by age 68. Foreign-service employees at the State Department are out at 65. Mandatory retirements are mostly verboten in the United States. But there are some professions with such intense physical and mental demands, that require such high-stakes decision-making and mental acuity, that we’ve decided they’re just different.

There’s been a minimum age limit to hold various federal offices for centuries. For the House of Representatives, it’s 25. For the Senate, it’s 30. For the presidency, it’s 35. This doesn’t mean that no one under age 25 could ever serve competently in the House, or that everyone over 25 belongs there. After all, the current age requirement failed to keep out Madison Cawthorn, now 27.

Really, though, these are all arbitrary numbers, set by the Founders in a far different time. The average age among signers of the Declaration of Independence was 44. Jefferson was 33. He, John Adams, and George Washington all left office at 65. In the current Senate, the oldest in history, 65 is fairly spritely—a bit above the median of 64. Twenty-seven members are in their 70s, and seven are in their 80s. The Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, is 82. Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader in the Senate, is 80. The president of the United States, Joe Biden, is turning 80 in November. The median age of an American person is 38.

In April, two U. S. senators who’ve served with Dianne Feinstein for years told the San Francisco Chronicle that sometimes she does not fully recognize them. They were joined by two other senators in questioning, anonymously, whether the 89-year-old Feinstein is still fit to fulfill her duties representing the nearly 40 million people of California. Her aides have reported that she sometimes forgets things they just briefed her on—or that the briefing happened at all. At a 2020 hearing with then Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, Feinstein asked him the exact same question twice, as though she had no idea she’d just asked it. At the time, she was the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, a perch from which she helped oversee confirmation hearings for Supreme Court justices who will adjudicate American law for decades after she’s gone.

Feinstein is an extreme example. But a large volume of research on cognitive decline and aging is clear that by your 70s, and particularly your late 70s, you are likely to experience some significant decline in your memory and reasoning capabilities. We’ve made huge advances in medical science to keep human bodies functioning longer. Have we made the advances to match when it comes to the functioning of human minds?

House and Senate committees regularly hold hearings with Silicon Valley CEOs, nominally on the issue of Big Tech monopolies and what must be done about them. There you can find senators using their five minutes to ask Mark Zuckerberg how he makes money when people don’t pay for his service—“Senator, we run ads”—or how they can stop getting ads for chocolate. Sixty-seven-year-old Lindsey Graham, a spring chicken for this bunch, was bragging as recently as 2015 that he had never sent an email. These are the people who are going to repeal Section 230 and craft legislation to replace it? At what point are folks who’ve spent most of their lives ordering from the Sears catalog unfit to regulate Amazon? And it’s not just tech. When the Supreme Court tossed Roe v. Wade, the number-three House Democrat, Jim Clyburn, 82, said the decision was “a little anticlimactic” and that he hoped to find “the extent to which we can move legislatively to respond.” Not exactly channeling the fury of the young women who form a vital part of the Democratic base.

This article appears in the September 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

There is value in having experienced legislators around. This is actually one of the primary arguments against (age-agnostic) term limits, a policy that in theory would cut down on corruption and cronyism by removing entrenched power players. In practice, though, term limits can enhance the power of lobbyists and industry insiders, who become the only force in the policy-making process that remains constant over years and decades as more inexperienced lawmakers cycle in and out. Term limits alone would also not necessarily prevent the phenomenon of 90-year-old senators. And by the way, state political machines are often quite happy with gerontocrats running for as long as they like. It raises the probability that they’ll leave office mid-term, at which point their governors would appoint a replacement—who, in turn, will not forget the gesture when they run with an incumbent’s advantage the next cycle.

Not that everyone on the older side is unfit. Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, 76, defeated young upstart Joe Kennedy III in a 2020 primary in part by harnessing the energy of youth climate activists. Elizabeth Warren, Mitch McConnell, and Nancy Pelosi are all still, whatever you think of their politics, formidable. Grassley has authored a bill to take on monopolization in the meatpacking industry that’s won praise from experts and across the aisle. Bernie Sanders transformed American politics when he ran for president in 2016, at age 74. In a different political culture, though, could he have become a national figure earlier in his career—and his life? How much does an entrenched class of older political power players discourage younger people from getting into the game?

Taking a hard look at our gerontocracy can be a demoralizing experience. It’s difficult to dispute that Joe Biden at 79 is not the same Joe Biden who danced circles around Paul Ryan at a vice-presidential debate in 2012. Does this mean he is unfit to serve? So far, it doesn’t appear so. Though in July, The New York Times reported that a Biden aide deemed ten days of international travel “crazy” for the aging president. And his approval ratings among younger Americans have sunk into the toilet. Maybe it’s inflation, or maybe it’s that he’s conspicuously old, struggling through speeches and even to move around the podium. It’s hard to see a bold future when the present looks like the past. Or maybe it’s that after years of his party describing the climate crisis as an existential threat to human civilization as we know it, the Democrats have so far mostly just secured some funding for electric-vehicle chargers.

Are these the kinds of results we’d get if the country were run by the generations that will experience far worse fires and floods and drought? I’m willing to find out. It’s not that older folks, who make up a significant chunk of the American population, shouldn’t be properly represented in the halls of power. It’s that they’re way overrepresented, and it is bending the trajectory of our national life. The American story has been crowded out by the story of the baby-boomer generation.

In China, the Communist-party leadership is usually out at 68, though Xi Jinping blew right through that. The benefits of being President for Life. We’d like to think we do things differently over here, not least because we’ve long prided ourselves on the dynamism of democratic life as compared with our totalitarian frenemies. By the time Gorbachev took the reins amid the Soviet Union’s steep decline in the mid-to-late 1980s, the Politburo was going stale, staffed with apparatchiks of such advanced age that it became a target of derision in the West. It’s not hard to see why: An aging governing class calcifies decision-making and makes a country less nimble and forward-looking. Let’s avoid the same fate and not merely encourage our elder leaders to retire. Let’s require it. Call it ageism if you want, but let’s get ourselves a maximum to go with our minimum: Once you turn 80, you can’t run for public office anymore. Go spend some more time with the grandkids—it’s the law.

You Might Also Like