The Case Against Training Based on Your Menstrual Cycle

This article originally appeared on Outside

In the ongoing quest to ensure that women are well served by sports science, there's a subtle tension between two conflicting impulses. One is to emphasize the many ways that women are different from men, and the resulting need for woman-specific training guidance derived from woman-only studies. The other is to emphasize the many ways that women are similar to men, and the resulting need to stop excluding them from existing research initiatives and stop making training advice more complicated than it needs to be.

There's merit in both perspectives, so finding the right balance can be tricky. Keep that tension in mind as you consider the results of a new systematic review, published in Frontiers in Sports and Active Living by a team led by Lauren Colenso-Semple of McMaster University in Canada, that assesses the effects of menstrual cycle phase on strength and adaptations to strength training. Colenso-Semple and her colleagues don't pull their punches: they don't think the claim that strength or trainability varies over the menstrual cycle is supported by the evidence, and they don't think we should be issuing training advice on that basis.

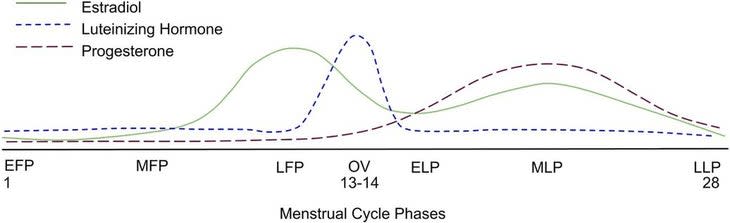

It’s certainly true that hormone levels vary dramatically in women over the course of a menstrual cycle, in contrast to the relatively stable hormone levels in men. Here's a diagram showing the typical pattern of estradiol (a form of estrogen), luteinizing hormone, and progesterone across the cycle:

You can broadly split the cycle into three phases: follicular, starting with the beginning of menstruation and ending with ovulation; ovulatory, which only lasts for about a day; and luteal, which follows ovulation until the next period begins.

In practice, as the diagram above shows, there can be significant hormonal differences even within a phase. For example, estradiol is low early in the follicular phase (EFP) and peaks in the late follicular phase (LFP). Still, studies on cycle-based training have generally stuck with a simple breakdown: train hard during the follicular phase, then back off during the luteal phase.

Why should phase matter? Estrogen (and perhaps progesterone) are thought to play roles analogous to testosterone in men in the regulation of muscle mass. I say "thought to" because there's a huge gap in research on the topic. If you take the estrogen-producing ovaries out of rodents, they lose muscle mass. And the gradual decline in hormone levels that follows menopause is also thought to contribute to muscle loss. But whether either of these lines of evidence tell us anything about the effects of day-to-day variations in hormone levels is unclear.

The new paper takes a critical look at five previous reviews and meta-analyses (including one from 2020 that I wrote about here, which includes endurance performance as well as strength), all of which aggregated training and performance data from multiple studies. Three of the reviews concluded that cycle phase doesn't influence strength performance. The other two, according to Colenso-Semple, drew inappropriate conclusions based on insufficient or inappropriately analyzed data.

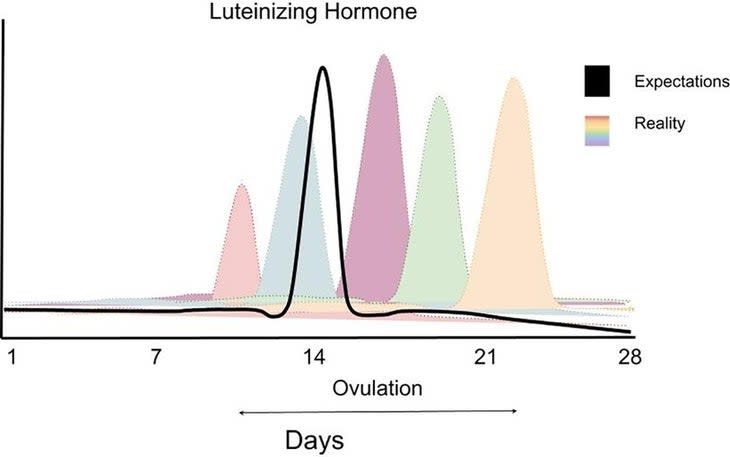

In all cases, the general quality of the individual studies was low. One of the biggest and most widespread limitations was in the methods used to verify cycle phase. Simply knowing when you last menstruated is insufficient to determine your current hormone levels, the authors point out. There's huge variation in phase length, both among different people and within an individual's consecutive cycles. Here's an illustration from the paper showing the contrast between expected fluctuations in luteinizing hormone (in black) and what you actually observe in a group of women (various colors):

Even some of the supposedly more rigorous approaches, like watching for changes in basal body temperature to signal ovulation, are unreliable. The best option is to confirm ovulation with a simple urine or blood test.

This sounds like a methodological problem for researchers, but it's actually a more fundamental practical problem for exercisers. Even if we eventually establish that certain combinations of hormone levels are more conducive to certain types of training, how do you make use of that information if you're not really sure what your current hormone levels are and can't predict how they'll change over the days to come? You could take regular urine tests--but you'd probably want to be sure that there's a significant benefit to training according to your cycle before going to all that trouble.

There's lots more detail in the journal article (which is freely available to read), so I won't belabor the point. Suffice to say that, in the opinion of Colenso-Semple and her colleagues, there's no convincing evidence that you need to adapt your training based on your menstrual cycle. This eliminates the main excuse used by researchers to exclude women from their studies, so here's hoping the scientific establishment takes note.

But figuring out what message women should take from these results is a little trickier, as I noted at the top. It might seem tempting to take a hard line and say, "Well, there's apparently no evidence that performance varies with the menstrual cycle, therefore we should never mention it again." But that's thoroughly contradicted by the actual experience of female athletes. In a 2021 survey of more than 1,000 athletes, nearly half of them reported sometimes missing training due to symptoms related to menstruation or hormonal contraceptive use.

Colenso-Semple and her colleagues thread this needle by concluding that there's no basis for systematic training recommendations based on the menstrual cycle, but that strength training programs should be tailored to individuals based on factors that might include the menstrual cycle. In practice, that means tracking your cycle and keeping training records that are detailed enough to tease out any recurring patterns of better or worse performance. But it also means that you don't need to go looking for problems: if you can't detect an effect, it's probably not big enough to worry about. The one takeaway that everyone would agree with, of course, is the same one that concludes all articles about women in sports science: more research is needed.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.