Canada's Indigenous Cuisine Is Booming — Here's Where to Taste It

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

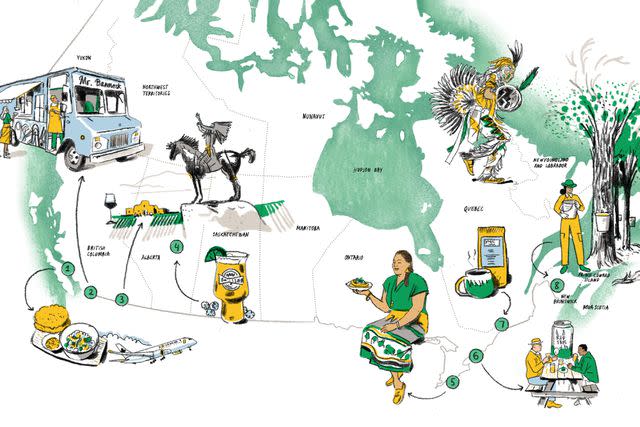

A growing contingent of Indigenous-owned food ventures offers visitors a delicious way to explore Canada’s culture and cuisine.

Peter Oumanski

In the warmer months at powwows all over Canada, Indigenous communities gather to celebrate our culture, music, and food in ways that engage all the senses: Competitive dancers wear vibrant regalia, the sound of jingle cones stitched to their outfits matches the rhythm of drums while they move, and the aroma of cooking in the air is a constant reminder that food is a mainstay of the festivities.

There are vendors selling chilled and sweetened strawberry juice, grilled bison burgers, and Navajo tacos made of fry bread (called bannock in Canada) and topped with ground meat, chopped tomatoes, lettuce, and shredded cheese. It’s a beloved but controversial fixture of powwow cuisine, sometimes referred to as an “Indian” taco, a problematic and outdated catchall name for a diverse group of people who now go by Indigenous, First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, or also by their more specific communities. (For example, you can call me Indigenous, First Nations, or Mohawk.)

Powwow cuisine — Navajo tacos and all — is a major draw for attendees at these annual festivities, which take place over weekends in the summer on reserves or at urban centers across the country before moving on to the next location. Luckily for visitors to Canada and locals like me alike, a small but mighty group of Indigenous-owned food and drink businesses are finding footholds in the industry, bringing not only powwow cuisine but also other Indigenous staples to diners year-round.

My own reserve, the Six Nations of the Grand River in southern Ontario, recently saw the opening of the first Indigenous-led restaurant in our community, Yawékon, helmed by Six Nations chef Tawnya Brant, who competed on Top Chef Canada last year. Brant’s menu pulls traditional ingredients into comforting dishes like bison shepherd’s pie and turkey gravy over blue-corn dumplings. From my own experience, and having seen the restaurant’s reception, I can share that it is wildly meaningful when a community member brings their talents home, aiming to create better and more wholesome cuisine.

Peter Oumanski

Being able to walk into an Indigenous-owned restaurant or see a shelf full of Indigenous-made products makes me feel acknowledged in a way that doesn’t happen often. And for non-Indigenous people, it’s a great opportunity to learn about our approach to food and drink and to support our businesses.

Just as there are more than 630 First Nations communities within Canada, as well as Métis and Inuit, with their own different cultures, traditions, and languages, there are a variety of representations of Indigenous foods across the country. Some restaurateurs, chefs, and entrepreneurs are focused on using precolonial ingredients like berries, wild rice, and corn, while others bring fusion dishes and global techniques to their menus. Some are popping up in unexpected spaces.

Salmon n’ Bannock is a surprising discovery for travelers at Vancouver International Airport. Canada’s first Indigenous fast-casual airport restaurant offers grab-and-go foods like candied salmon, bison sandwiches, and sweet potato poutine. The airport location is an offshoot of the original Salmon n’ Bannock in downtown Vancouver.

“It’s interesting because a lot of foreign travelers still don’t really understand that we’re Indigenous,” says owner Inez Cook, who is Nuxalk. “More Canadians know what bannock is, even if they haven’t tried it, so when they see that, they already know that it’s an Indigenous restaurant.”

Visitors can also find powwow food in Vancouver at Mr. Bannock, a food truck owned by Squamish chef Paul Natrall, who uses social media to post the truck’s location each day before people come to line up for smoked-meat tacos and the rotating weekly fusion dish.

“That’s the goal: to make Indigenous foods mainstream and to be able to showcase Indigenous foods on a national level,” says Natrall. “I’m super excited and definitely proud of the work that I’ve done so far, but at the same time, there’s a lot more work to do.”

Indigenous-made products can also come home with you. Many retailers, particularly concentrated in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, sell bottles of maple syrup by female-owned company Wabanaki. The company takes what is a traditional Indigenous food—syrup was harvested and boiled before the settlers arrived—and updates it by aging it in bourbon, whiskey, and toasted oak barrels.

In the drinks space, there are a variety of options. The Osoyoos Indian Reserve’s Nk’Mip Cellars is the first Indigenous-owned winery in North America, creating award-winning Chardonnay and Pinot Noir; Métis-owned Dog Island Brewing in northern Alberta creates raspberry wheat beers and IPAs; while in Toronto, Inuit-co-owned Red Tape Brewery produces pilsners, sours, and bespoke brews.

Birch Bark Coffee Company is another great option for gifts to bring back home. The Ojibwe-owned enterprise sells six different blends of Fair Trade–certified organic beans. Birch Bark’s Mark Marsolais-Nahwegahbow sees an increasing number of Indigenous food traditions going mainstream.

“We are seeing more small stores opening with traditional products being sold: more strawberry drinks, Indigenous herbal teas, and coffees,” he says. “Some people purchase them because they wish to support us, but once they try the product, they become fans and continue to support and spread the word.”

For more Food & Wine news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Food & Wine.