I Came for the Lamb Recipes, I Stayed for the Best Cookbook Writing of the Year

“The lovers of this dish anticipate the spring when the ram’s testicles are at their biggest.” “Women long believed that a stroll in a lettuce orchard would purify their souls and give them eternal youth.” Unet Beni is a lamb meatball soup made on the day houseguests leave in order to convey the message, “Don’t forget how I looked after you.”

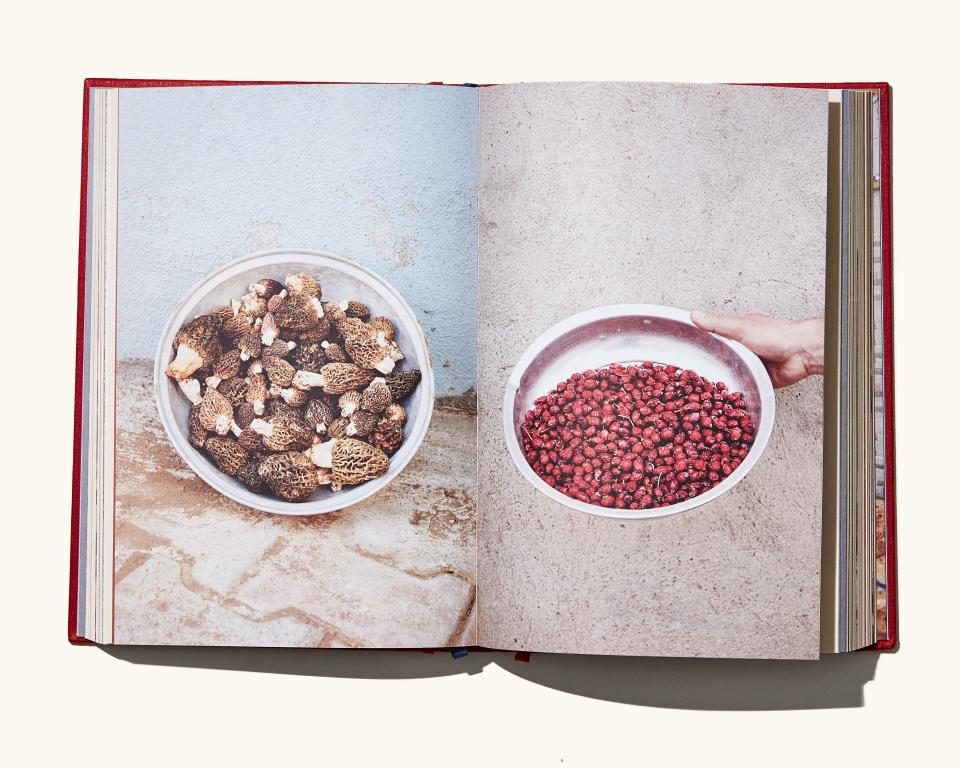

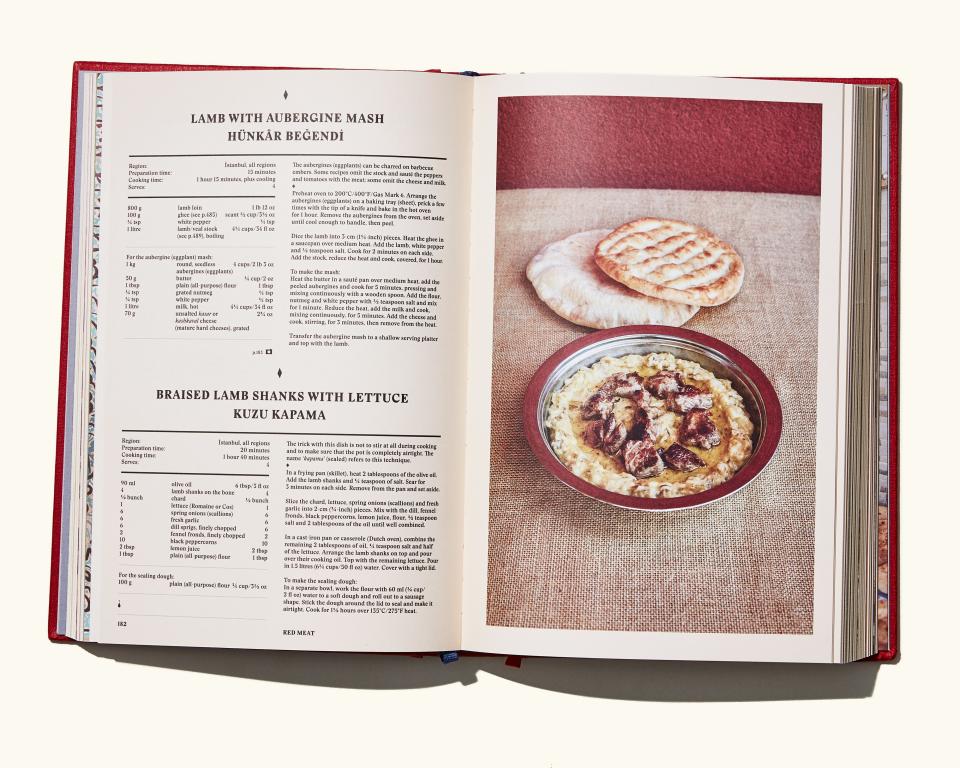

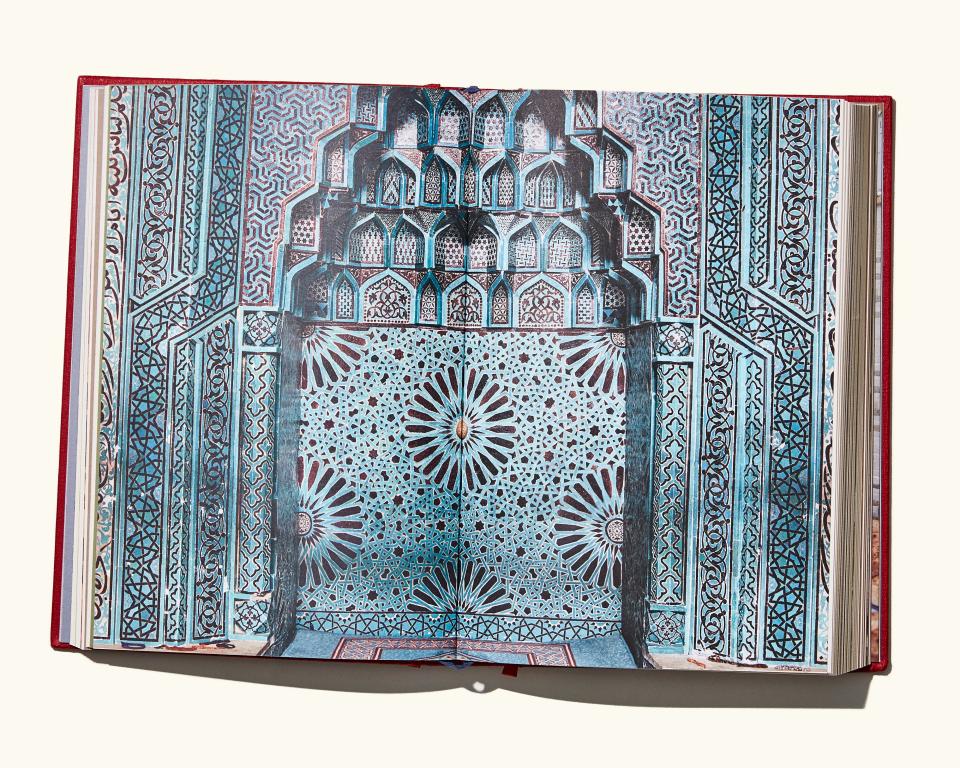

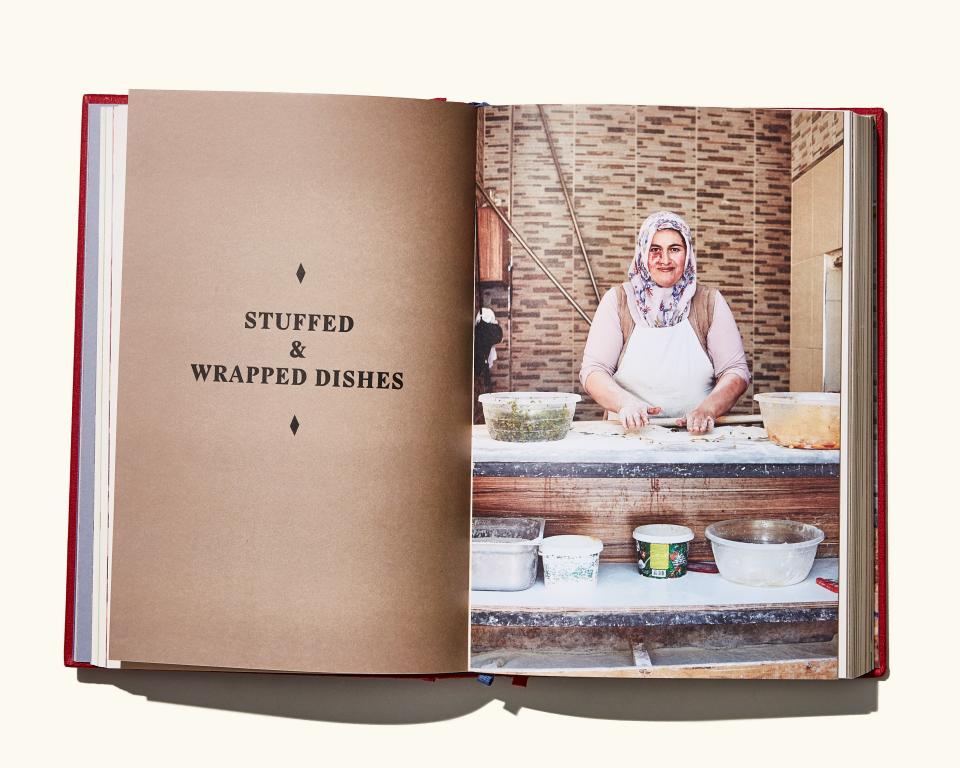

These are just a few of the narratives that fill The Turkish Cookbook, Musa Dağdeviren’s stunning new cookbook from Phaidon. Like most books from the publisher, what at first appears to be a heavy, linen-wrapped coffee table book is much more. Every recipe, and the opening of every chapter, packs in the folklore and cultural background for each dish. It’s a remarkable feat of scholarship, but that doesn’t mean it’s a boring textbook. Dağdeviren’s way of writing (short, descriptive, to the point) makes it riveting. I found myself reading through the 512 pages for hours, as if it were a novel.

Dağdeviren was the perfect candidate for the book. He rose to fame in the late ’80s, first with a kebab joint in Istanbul and then Çiya Sofrasi, a world-renowned restaurant that features dishes from every region of Turkey, prepared traditionally. Before opening, Dağdeviren had traveled across the country, cooking with elders and grandmothers, preparing to write a book, when the restaurant opportunity came instead. In an episode of Chef’s Table about his work, which now includes teaching high school students about Turkish cuisine and leading a food research foundation, you hear all about Dağdeviren’s political awakening (he led a campaign to unionize bakers) but his food is often whisked away or tucked into a blazing wood-fired oven. With The Turkish Cookbook, Dağgdeviren completes what he set out to do, putting the food, the cultural context, and people who make it in focus.

Take, for example, the soup chapter which opens with a note on cooking technique, an explanation of tarhana (a fermented hulled wheat and yogurt ingredient that’s added to soups), and a poignant mini-essay on soup “as social memory.” “It announces and facilitates our joy, grief, pain, and lives,” writes Dağdeviren, listing soups designated for festivals, weddings, illness, and mourning. The recipes that follow suddenly represent more than a bowl of something hot when the weather’s cold. A portion of Nohut Çorbası, a chickpea soup, is poured over dry fields during times of drought in hope for rain; a lamb’s brain soup is believed to help ease anxiety and support memory; a head and trotter soup is made for a family in mourning, to be distributed to seven neighbors and the poor to help the soul of the recently deceased comfortably pass on. When’s the last time I cooked something, other than a birthday cake, that meant something deeper?

The dishes revolving around marriage I also found intriguing—as well as far cries from the kinds of traditions I’ve taken part in (like rehearsal dinners in windowless rooms with soggy Caesar salad). In Veiled Rice Pilaf, a wedding banquet dish, “pine nuts represent the groom, the almonds the bride, the currants the children, and the pastry the home. The rice is believed to bring prosperity.” A pistachio cordial drink is made for a prospective groom when visiting his bride’s house. “Offered after the salty coffee, it represents the change from salty to sweet and ends the visit on a good note.” Many dishes are “litmus tests” for brides to be, such as onions stuffed with veal tomato, bulgar, and chili flakes, made in four versions (spicy, sweet, salty, and sour) to “symbolize the balancing act of marriage.” Meatballs stuffed with walnut-stuffed apricots (makiyan) are “made on the last day a new bride spends with her parents in the hope that her new home will enjoy good health, happiness, and fortune.” There aren’t so many tests for grooms, sadly, but there is a recipe for scrambled eggs with vegetables beloved by bachelors and college students.

I’m not exaggerating when I say I spent hours reading it. The book feels like a collection of super-short stories that interconnect and echo each other, yet always end with a delicious plate of something. But that’s not to suggest that the more than 500 recipes included are an afterthought. Many are very cookable and calling to me. I flagged a baked fish with tahini sauce, an almond tzatziki, and lamb meatballs with walnut rice.

Dağdeviren has pulled off a work of literary art and culinary history, which would sound sort of pompous if it weren’t true. I promise it’s true. It’s not every day you come across a cookbook that transports you so deeply away from your world and into another, and for those from across the expanse of Turkey—takes you home.

Buy it: The Turkish Cookbook, $32 on Amazon

All products featured on Bonappetit.com are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit